Document 13089115

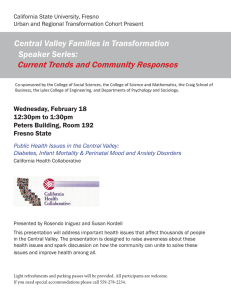

advertisement