CRS Report for Congress California’s San Joaquin Valley: A Region in Transition

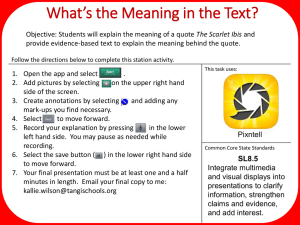

advertisement