The Library Study at Fresno State

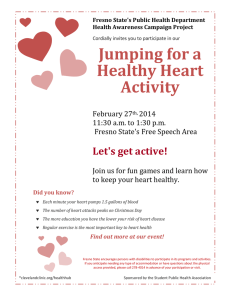

advertisement