Case Study 1: An Evidence Based Practice Review Report

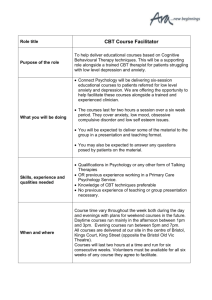

advertisement