1 Case Study 1: An Evidence-Based Practice Review Report

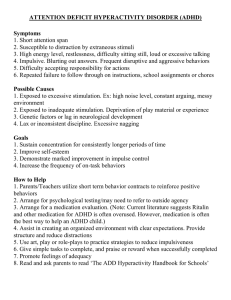

advertisement