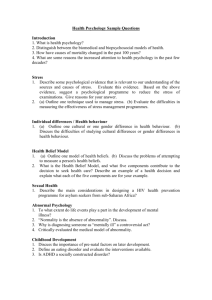

Psychology Biological Psychology 9008

advertisement