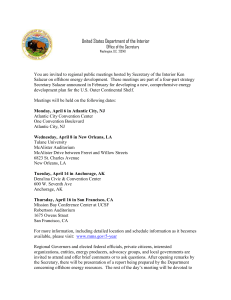

The Regulation of Oil and ... on the Outer Continental Shelf:

advertisement

The Regulation of Oil and Gas Development

on the Outer Continental Shelf:

Georges Bank

Energy Regulation

Summer, 1981

Professor Gary Ahrens

By

Steve Henry

•

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

1

I.

The Outer Continental Shelf Act Amendments of 1978

2

II.

Specific Powers of the Secretary of the Interior

Under the OCS Lands Act

8

III. Georges Bank

A.

11

OCS Jurisdiction of the Georges Bank and

similar problematic regions

13

B.

Recent OCS Litigation

16

c.

Future Directions of OCS Development

19

23

CONCLUSION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

:

__ _fOOTNOTES

•

001J.3

INTRODUCTION

The

regulation

of

oil

and

gas

development

States is premised on two primary concerns:

natural

resources

for

future

in

the

United

one, conservation of

necessity

and

present

econom1c

stability, and two, conservation of the environment.

As

the

United

States

petroleum

for

personal

aneously,

environmentally

becomes

and

increasingly

industrial

aware,

of

usage

greater

dependent

and,

contempor-

importance

linking petroleum and the environment become.

upon

1ssues

The dependence and

necessity upon and for petroleum and its derivatives continues to

A society diverse

be without question.

values

recognizes

both

while

exist among these related,

cern.

awaiting

in social

the

and

economic

possibilities

but often neutralizing,

which

areas of con-

However, such a society is without a general and conclusive

understanding of environmental factors and their intertwining with

society's need for petroleum products and production.

The OCS

has

been

called

"America's

best

hope

for

finding

additional oil and gas resources and reducing our dependence on

foreign oil." 1

continental

jurisdiction

Indeed,

shelf

and

beneath the

and

slope

control,

over

there

1. 3 mill ion square miles of

which

exists

the

an

United

enormous

States

quantity

has

of

Demonstrated reserves of offshore oil and gas

energy resources.

are approximately 3.5 billion barrels of oil and 36 trillion cubic

feet of gas, wfth prospective reserves of an additional

8 to 50

billion

feet

barrels

of

oil

and

28

001J.J

to

1

199

trillion

cubic

of

2

gas.2

Although

production

only

currently

17

percent

comes

from

of

the

domestic

oil

continental

and

shelf,

gas

some

studies estimate that offshore oil and gas may comprise as much as

u.

one-fourth to one-third of total

The

balance of

this

S. production by 1985.3

composition will

explore

the

immediate and future effects petroleum development on

Continental

She! f

might

have

on

the

Georges

Bank

possible

the Outer

area

of

the

United States' eastern seaboard.

I.

The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act Amendments of 1978

The purpose of the Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act4 is to

regulate the granting of mineral leases on the OCS by the federal

government.

The Act authorizes the Secretary of the Interior to

grant mineral leases on the OCS and to prescribe regulations for

their administration.

The federal government's jurisdiction over

the OCS extends from the limits of state boundaries seaward to a

'

depth of 200 meters or, according to the 1958 Geneva Convention,

beyond that point "to where the depth of the super-adjacent waters

admits for the exploitation of the natural resources."5

The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act of 1953,

document and basis of

today's

act,

called

for

a

the original

"carte blanche

delegation of authority to the Secretary of the Interior." 6

OCS

Lands Act Amendments

•

of

1978 7 represent

some

The

congressional

•

dissatisfaction with the Interior Department's administration of

('"":'\

001 .<.·V

3

the OCS Lands Act, but more importantly they reflect the growth in

power of several political pressure groups during the past quarter

century.

Analysis of the 1978 amendments reveals that they respond to

four general

area

of

areas

criticism,

of

critic ism of

expressed

by

the

1953

consumer

act. 8

The

activists,

first

asserted,

collectively, that the primary leasing method in use

(cash bonus

bidding

competitive

with

results, 9

value"

a

that

for

fixed

the

its

royalty)

government

leases,10

has

has

and

not

not

that

produced

received

big

oil

"fair

market

companies

have

enjoyed an unfair advantage 1n the lease-sale market.11

A second body of opinion, representing environmental groups,

land use planners, and critics of conventional market-based energy

decision making,

its

economic

wanted the federal government to expand greatly

planning

role

in

respect

to

OCS

energy

resour-

ces. 12

The third area of criticism, coastal state politicians (supported

by environmental

groups

and

state

planners)

argued

they should be given increased powers over decisions

that

concerning

the location, timing, and scope of energy exploration and production

activities

being

conducted

near

constituent

coastlines. 13

And the fourth area of criticism is that governors of coastal

states and private groups whose interests conflicted with offshore

energy

.

development

wanted

a

measure

of

financial

protection

against the risk of losses that the governors and private groups

might bear as a result of OCS mineral leasing.

4

The 1953 legislation provided for bonus, rental, and royalty

payments to be made to the federal government from OCS leasing but

gave no share of this revenue to coastal states, which nevertheless were expected to accept the risk of economic and environmental damage

opposed

the

resulting

proposed

states

affected

and

by

OCS

leasing

in

commercial

OCS

impact or damage

Barbara-type

from

adjacent

insurance

wanted

funds

in

Thus,

federal

fishermen

developments

incident,

development.

and

other

was

a

many

states

waters. 14

What

private

groups

source

econom~c

of

the event of another Santa

therefore avoiding

the

need

1953

OCS

for

lawsuits

for recovery of damages suffered. 15

Under guidelines

the

Interior

procedures

established

Department

for

its

has

OCS

by

the

established

leasing

a

Lands

well-defined

program. 17

When

Act, 16

set

of

followed,

these guidlines satisfy all legal and equitable requirements for

all parties involved.

The leasing process begins with a call for

tract . nominations and comments from industry and the public.

On

'

-the

basis

leasing

impact

of

these

responses,

are defined

studies

statement

are

drafts

by

then

become

the

geographic

Interior

identified

When

public

for

Environmental

Department.

initiated.

available,

areas

environmental

hearings

are

impact

held

~n

which industry, environmental groups, state and local governments,

and other interested groups are invited to comment.

of witness

.

testimony,

final

environmental

impact

On the basis

statements

are

then prepared and submitted to the President's Council on Environmental Quality.

The Secretary of

the

Interior makes

the

final

5

decisions

as

to whether

restrictions

are

to

to

be

hold

a

included

sale

in

and

the

what

environmental

lease-sale

terms. 18

Only two methods of bidding were authorized under the

act.

If

a

lease-sale

was

authorized,

interested

parties

invited to submit sealed bids on the basis of either

bonus bid with a fixed royalty or

1978

(2)

1953

were

( 1) a cash

a pure royalty bid.

amendments give more comprehensive regulatory and

The

planning

powers to various federal and state administrative agencies.

The

economic significance of ·certain provisions in the 1978 amendments

are

based

upon

distribution

their

probable

effects. 19

The

resource

1978

allocation

legislation

nificant expansion in economic planning.

is

required

to

revisions.20

provide

a

five-year

and

income

mandates

a

sig-

The Interior Secretary

leasing

The plan is to consist of a

plan

with

annual

schedule of proposed

lease· sales and requires management of the OCS in a manner which

considers

renewable

The

.

and

continues

environmental

resources

non-renewable

act

1978

and

social,

econom~c,

the

values

the

therein. 2 1

contained

requirement

of

that

leases

be

allocated on a competitive basis and authorizes the two methods of

bidding

addition,

specifically

it

authorizes

bidding systems:

(1)

for

called

the

by

adoption

the

of

any

1953

of

act. 22

the

In

following

a variable royalty bid with a fixed work

commitment based on a dollar amount for exploration, (2)

a cash

bonus bid' or work commitment bid with a fixed cash bonus' and a

diminishing or sliding royalty, (3)

a cash bonus bid with a fixed

share of the net profits at a rate of not less than 30 percent,

,.

001 ~)~

I

'.',

, .•

r.:.._;~

6

(4)

a net profits bid with a fixed cash bonus, (5)

a cash bonus

-bid with a fixed royalty and a net profits interest, and (6)

a

work commitment

alty. 23

bid

Moreover,

with

a

fixed

cash

the Secretary of

bonus

the

and

Interior

to adopt any other system of bid variables,

a

fixed

is

roy-

authorized

terms and conditions

which is determined to be useful to accomplish the act's purposes,

unless

disapproved

also requires

by

the

Senate

that bidding

or

House.24

systems other than

The

bonus

1978

act

bidding

be

applied to not less than 20 percent and not more than 60 percent

of the

years

total

area offered

following

the

for

act's

leasing during

passage.

This

each of

is

the

subject

to

five

the

Secretary of the Interior determining that such a requirement is

"inconsistent with the purposes and policies" of the act.25

As did the

1953 act,

the 1978 act authorizes

the

grant of

leases to "qualified" persons but contains no restrictions as to

citizenship.26

Proposed

regulations

Management seek to restrict

of

the

the holding of

Bureau

leases

to

of

Land

citizens,

--resident aliens, or corporations of the United States or of

states

or

Court

territories.27

challenges

to

this

its

inter-

agency policy variance have, for whatever reason, not surfaced to

any referrable degree.

Foreign corporations under the 1978 amend-

ments are allowed to use domestic subsidiaries.

Decisions

as

~

to

resource management.

who

may

hold

leases

Resource management

bears

is

directly

upon

the maintaining of

all the subject resources, i.e. oil, gas and fish, which are located within a given area and subject to statutory management.

001° ~..

-

The

7

purpose of efficient resource management appears to be served by

the existing system, which permits open competition but guarantees

the federal government legal jurisdiction over its Outer Continental Shelf lessees.

This purpose is also served by the absence

of any restrictions on the number of acres that any operator can

hold under lease.

The 1978 act continues the requirement of the 1953 act that

oil and gas leases endure for an initial period of five years "and

as long after such initial period as oil and gas is produced from

the

area

in

operations

on."28

paying

as

quantities,

approved

unlike the

by

the

1953 act,

or

drilling

Secretary

however,

the

or

are

well

reworking

conducted

1978

act

there-

allows

the

Secretary of the Interior to issue leases for an· initial period of

up to ten years where the longer period is necessary "to encourage exploration and development in areas because of unusually deep

water

or

other

unusually

conditions." 2 9

adverse

This

amendment should satisfy those who have suggested that a five-year

primary term for oil and gas leases may be too short with respect

to drilling on the continental slope and in areas such as Alaska

where ope rat ions must

be

conducted

on

a

short

season

bas is. 30

It remains to be seen what effect this particular amendment will

have on

the

development.

Georges

Bank due

to

that

area's

relatively

recent

8

II.

Specific Powers of the Secretary of the Interior

Under the OCS Lands Act

The OCS Lands Act authorizes the Secretary to "prescribe and

amend such rules and regulations as he determines to be necessary

and proper in order to provide for the prevention of waste

conservation of

Shelf ••• " 31

in

Gulf

Oil

the

resources

of

that

Morton3 2

v.

Corp.

the

Outer Continental

it had earlier decided

that

the

words,

"natural

1n the Act include all the natural resources of the

continental

ces. 33

natural

The court pointed out

resources,"

outer

the

and

Thus,

shelf

the

conservation

and

not

Secretary

of

the

may

merely

issue

marine

the

mineral

regulations

environment

and

resour-

to

promote

other

natural

resources in addition to oil and gas.

The Secretary would appear to have broad powers to regulate

lessees' activities after the lease has been granted.

the

authori ty34

statutory

granted

him,

the

Pursuant to

Secretary,

on

August 22, 1969, issued a regulation authorizing emergency suspension of

any

operation

which

irreparable harm or damage

property,

to

the

leased

"threatens

to

life,

deposits,

deposits or to the environment.

immediate,

serious,

including

aquatic

to

valuable

other

life,

or

to

mineral

Such emergency suspension shall

continue until in his judgment the threat or danger has terminated.35

emergency

Presumably,

in

suspension

•

Gulf

Oil,

authority

the

Secretary

provided

by

this

relied

on

regulation

the

in

•

refusing to allow. the

previously approved.36

installation of

a

platform that

had

been

9

In

Union

Oil

Co.

v.

Morton, 37

Union

Oil

argued

Secretary's action constituted a breach of

the

lease

that

the

agreement.

In the lease the Secretary granted Union "the right to construct

or erect ••• all

artificial

islands,

platforms,

fixed

or

floating

structures ••• necessary or convenient to the full enjoyment of the

rights granted by this

lease ...... 38

However,

in

addition,

the

lease provided that it was entered into "under, pursuant, and subject to the terms and provisions of the (Act), and to all lawful

and reasonable regulations of the

(Secretary) when not inconsis-

tent with any express and specific provisions herein, which are

made a part hereof •••• 11 39

The court

rejected

Union's

argument

and held that any terms of the lease which were inconsistent with

the

terms

of

the

statute

were

invalid. 40

The

court

reasoned

that the Secretary could alienate interests in land only to the

extent authorized by law, and that Congress had, in the OCS Lands

Act, authorized the Secretary to lease oil and gas rights with the

qualification that he retain the power to amend existing rules and

regulations or promulgate new ones whenever he deemed necessary to

do so for

the

conservation of

natural

Thus,

resources. 41

the

court determined that the action was taken by the Secretary was

not in violation of the lease agreement, as was alleged by Union.

The

court

Secretary's

then

action

considered

represented

ment's prohibitfon against

public

use

open-ended,

without

just

indefinite

the

the

a

questions

violation of

suspension

of

the

private

taking of

compensation.

of

The

the

court

right

whether

fifth

amend-

property

held

to

the

that

install

for

an

a

10

platform,

Act 42

even

the

and

amount to a

requiring

though

seemingly

authorized

regulations

cancellation of

compensation

under

lease

the

the

OCS

Lands

thereunder,43

issued

the

by

and,

fifth

therefore,

amendment. 44

would

a

taking

Addition-

ally, the court held that such a suspension requiring compensation

was

not

authorized

by

Congress

and

was

therefore

beyond

the

Secretary's power.45

Lessees are required to prepare and submit exploration plans

to

the

Secretary

for

approval. 46

The

Secretary

is

empowered

to require modifications of these plans as he deems necessary to

achieve

consistency

with

subsequently

regulations

the

provisions

issued

under

of

the

act

and

act.47

the

any

These

modifications are to be exercised after bidding has been completed

and

leases

have

been

After

issued.

exploration

begins,

the

Secretary is further empowered to order a suspension or temporary

prohibition or any exploration activities and require preparation

of

a

revised

exploration

plan. 4 8

,_Finally,

the

Secretary

may

require any lessee operating under an approved exploration plan to

obtain a permit prior to drilling.49

In response to demands from coastal states, the role of state

and

local

government

officials

in

exploration, and development has been

planning

for

lease

sales,

considerably expanded.

The

five-year leasing plan must be submitted to the governor of each

affected

request

state

a

•

for

review

and

modification require

comment. 50

a

written

0{)1 ().~

_,

•J

Any

reply

comments

by

the

which

Interior

11

secretary. 51

All

such

correspondence

must

to Congress with the proposed plan:s2

The

then

be

submitted

legislation

further

mandates· that "the Secretary shall accept recommendations of the

governor" if the Secretary determines that they provide a reasonable balance between the national interest and the well-being of

the

citizens

of

the

affected

state.53

Consultation

recommendations from officials of local government

with

and

jurisdictions

are also encouraged and solicited, and though the Secretary is not

constrained

to

accept

by

recommendations

desired.

such

recommendations,

governors,5 4

a

as

balance

in

the

is

case

of

nevertheless

For the newly required exploration and production plans,

the legislation specifies

that

the Secretary shall

not

grant

a

license or permit for any activity affecting land use or water use

in the coastal zone of a state unless the state concurs that the

activity

does

not

conflict

with

any

approved

coastal

zone

management plan.SS

Iri

remanding

the

case

to

the

trial

court,

the

court

of

appeals directed the lower court to determine whether the termination

of

the

Secretary's

suspension

order

was

sufficiently

"conditioned on the occurrence of events or the discovery of new

knowledge which can be anticipated within a reasonable amount of

time" to be a valid exercise of the Secretary's power and not a

fifth amendment taking beyond the Secretary's power. 56

•

III.

The

much

publicized

Georges Bank

Georges

001?8

Bank

region

exemplifies

the

12

counterforces

prevalent

where

industry

and

the

environment

seriously overlap.

Of particular interest is lease sale #42 which has been the

subject

of

litigation 57

is

and

being

considered

Commerce Department for a proposed marine sanctuary.

by

It

the

is now

the subject of public workshops.

In 1979, Secretary of the Interior Cecil Andrus told the New

England Business Council that "We have examined and re-examined,

reviewed

and

re-rev iewed

all of the pros

and

cons,

all

conflicts and consequences," on the proposed lease sale.

of

the

He said

"This North Atlantic area is the only promising frontier area off

the Lower 48 which has never had a lease sale."

Andrus said that

OCS oil and gas is a vital part of the answer to the energy future

of New England

and

the

U.s. 58

It

is

believed

that

lease

#42

has enough energy to keep Massachusetts in gasoline for over five

years.

Therefore, the balancing of interest becomes a necessity

heretofore thought to be perpetually delayable.

Andrus further said that the OCS Lands Act Amendments of 1978

provide him with additional authority to require the

use of the

best available and safest technologies economically achievable and

to suspend operations

harm to

the

and

environment

cancel

should

a

lease

develop.

if

unforeseen

Also,

under

risk or

the

Act,

funds are being established to compensate commercial fishermen for

damage to their ~ear and to finance the cleanup of any oil spills

on

the

funds.

Georges

Bank.59

The Act

creates

The

compensation

an Offshore

Oil

is

from

Pollution

earmarked

Compensation

13

Fund in an amount not to exceed $200 million.

This fund is to be

financed

per

by a

fee

of not more

than

3

cents

barrel

of

oil

produced from the Outer Continental Shelf, which is imposed on the

lessee

at

the

point

of

production.

The

fund

is

to

become

immediately available to compensate for oil spill removal costs,

the processing and settlement of claims,

and all

administrative

and personnel costs borne by the federal government arising out of

oil spills. 60

A.

On

OCS Jurisdiction of the Georges Bank

and similar problematic regions

February

1980,

4,

Massachusetts'

top

environmental

official said he would not grant licensing for offshore oil and

gas exploration in the Georges Bank unless all environmental safeUnder the federal Coastal Zone Management Act,

guards were met.

federal

activities

coastal

program.

particular,

drilling

the

be

consistent

Massachusetts

Massachusetts

1s deemed

traditional

must

fishing

grounds

has

CZM

consistent

with

plan

only

is

been

if

an

approved

so

approved.

provides

potential

"evaluated

that

In

offshore

damage

and

state

to

avoided"

the

and

"disposal of drilling muds and cuttings does not damage spawning

areas and fishing resources."61

The

right

resources

Act,62

as

is

to

assertively

.statutorily

amended,63

in

defend

g1ven

that

a

under

the

state's

the

Atlantic

own

Submerged

coastal

natural

Lands

states

or their municipalities own the coastal land mass, tidal regions,

0{)13_~

14

and seabeds of the marginal sea within three miles of their coastline. 64

Beyond

this

limit,

the

federal

has

government

jurisdiction over the territorial sea and submerged lands of the

OCS

to

whatever

Leasing,

are,

depth

exploration,

in theory,

seabed

resources

can

and production beyond

subject only to federal

be

the

exploited.65

three

mile

zone

regulation; nonetheless,

coastal states and municipal authorities retain proprietary power

over adjacent land areas critical to the siting of pipelines and

storage

and

processing

facilities.

Thus,

states

and

their

political subdivisions have the means to block the construction of

ancillary

facilities

largescale

commercial

necessary

to

the

development

Applicable

deposits.

federal

of

any

legislation

enhances this power.66

Where a company's proposed OCS activities will affect states

whose coastal zone management programs have been approved by the

National

Oceanic

and

Atmospheric

Administration

(NOAA)

of

the

Department of Commerce, the activities described in the company's

development plan must be certified as consistent with the affected

states' programs before they can be licensed by Interior.67

The underlying goal of the

Act68

is

to

encourage

a

Federal

strong

Coastal

management

governments

"in developing land and water

than

significance."69

local

incentives

..

to

•

develop

The

act

zone

coastal

Zone

role

Management

for

state

use decisions of more

offers

states

management

two

major

programs

in

conformity with federal guidelines:

money and increased leverage

over

the

federal

decisions

affecting

0{J)1,. ;

ry~

-'l

·.

\J'.

,

states'

coastal

zone.

15

Although the primary focus of the CZMA is upon local and regional

land use planning,

of national

planning for,

the act recognizes the need for accommodation

interests

including

"national

and in the siting of,

interest

facilities

involved

in

(including energy

facilities in, or which affect (the) state's coastal zone), which

are necessary to meet requirements which are other than local

nature." 70

state

to

This

provision

accommodate

has

not

national

siting of energy facilities

been

energy

in

read

needs

its coastal

as

by

compelling

permitting

zone.

in

The

state

a

the

is

simply admonished to "consider" this possibility in the course of

developing a coastal zone management program.

Recent amendments

expanding the grants available to states under the Coastal Energy

Impact Program (CEIP)

nevertheless encourage states to give such

sitings serious consideration.71

Outer continental shelf leasing is subject to the consistency

provisions of the CZMA even though the activity in question occurs

outside

the

affects

"any

state's

land

"coastal

use

or

zone,"

water

as

use

long

in

the

as

the

activity

coastal

zone." 72

OCS leasing activities are also subject to provisions of the CZMA

which have been interpreted as requiring that "all Federal license

and permit activities described in detail in OCS plans and which

significantly affect the coastal

zone

(be)

conducted in a manner

consistent with approved (state) programs.73

These provisions give coastal states leverage,

the degree of a

If

a

state

or

veto,

a

to

forestall

concerned

offshore leasing activities.

citizens

0()13J

though not to

group

objects

to

the

16

certification of

proposed OCS

activities,

the

license

applicant

must submit a new or amended plan unless the Secretary of Commerce

either

rides

makes

the

contrary

refusal

An aggrieved

to

state or

findings

certify

as

on

to

consistency74

national

local group can

security

elect

to

0

r

over-

grounds.75

contest

such

determination through the administrative process or challenge

a

it

in court; but even if an appeal is not taken, the power to delay

offshore

activities

states and

considerably

enhances

localities will henceforth be

leasing activity

in the OCS.

Although

the

able

the

influence

to

that

exercise

"national

over

security"

provisions of CZMA section 307(c)(3)(B) and liberal interpretation

of

the

commerce

Consitution 76

and

will

supremacy

permit

clauses

national

of

the

United

interests

to

be

States

given

preponderant weight, courts undoubtably will be left to determine

how the balance between these competing interests is to be struck.

Courts

will

also

be

left

to

resolve

difficult

constitutional

issues of preemption and interference with commerce.77

B.

Recent OCS Litigation

After a three-year legal battle,

General's office,

the U.S.

the Massachusetts Attorney

the Conservation Law Foundation of Boston, and

Interior and Commerce Departments reached

a

settlement

agreement to allow oil and gas exploration drilling to proceed on

~

the Georges Bank.78

The state and the conservation group said they were pleased

with the agreement,

although they plan to monitor environmental

tlul~~

17

permits and approval of exploration plans for the areas.79

The

McNaught

agreement,

in

the

Massachusetts,

approved

U.S.

settled

December

District

a

three

11,

Court

year

1980

for

court

by

the

fight

Judge

J.

District

of

by

the

state

attorney general's office and the Conservation Law Foundation to

block

offshore

Bank. 80

The

oil

and

lease

gas

sale

was

Lease

Sale

delayed

but

42

on

the

eventually

Georges

transpired

after the Interior Department agreed to environmental safeguards

to protect the fishing resources.81

The settlement agreement gave the state and the conservation

group access to federal studies already done, underway, or planned

in the future on Georges Bank.

"This (allows) us more convenient

access to scientific work before it

Douglas Foy,

executive director of

is formally released,"

said

the Conservation Law Founda-

tion.82

The agreement also committed the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of

the Commerce Department

to

re-evaluate

the nomination of a proposed marine sanctuary for the area, with

recommendations due

proposal

was

by December

dropped

when

1,

Interior

The marine

1981.

and

Commerce

sanctuary

agreed

on

the

Georges Bank plan in 1979.83

As might be suspected,

the efforts of Interior and the NOAA

to carry out their disparate responsibilities under the foregoing

statutes have provoked judicial challenges.

Suffolk

County8 4

and

Massachusetts85

The suits brought by

to

prevent

Interior

from proceeding with the Baltimore Canyon and Georges Bank lease

0{1130

18

sales, and those brought on behalf of oil companies to enjoin the

NOAA's

approval

Coastal

Zone Management Programs are of particular

June

30,

of

1976,

California86

the

following

a

year

Massachusetts87

and

of

interest.

prelease

planning

On

and

review, the Secretary of the Interior announced his intention to

conduct the first Atlantic OCS lease sale

six weeks of that date.

Defense

Council

and

(Lease Sale 40) within

Almost immediately the Natural Resources

representatives

of

local

communities

and

citizens groups who feared the impact of adjacent OCS operations

on nearby fishing grounds and beaches joined with the Long Island

counties of Suffolk and Nassau to seek to enjoin Interior

proceeding

with

the

contemplated

injunction was granted and stayed,

sale.88

After

a

from

preliminary

the case proceeded to trial.

On February 17, 1977, following a lengthy hearing on the merits,

the United States District Court for the Eastern District of New

York declared

the exploratory leases granted by

Interior

to

be

void and enjoined Interior form permitting leaseholders to conduct

further

The

exploration.

court

found

that

the

Secretary

had

violated NEPA by preparing an EIS which failed to weigh the range

and

effect

production tation

being

of

potential

onshore

impacts

arising

from

future

in particular, the possibility of pipeline transporbarred

by

state

statutes

or

local

ordinances, 89

as well as the environmental risk associated with specific pipe1 ine routes.

.

Judge Weinstein's decision to enjoin was based on

the premise that allowing the companies to proceed with exploratory activities

under

the

terms of

their

lease

represented

an

19

irreversible commitment of resources.90

The

Court

of

Appeals

for

the

Second

Circuit

subsequently

reversed the District Court's decision, concluding that the lower

court's finding of material NEPA violations was in error, and the

Interior's sale of leases did not represent federal action which

"irrevocably committed specific public resources to

damage

from

the

outset."91

In

the

Second

Interior had acted reasonably in deferring

irreversible

Circuit's

view,

consideration of

the

impact of local land use controls upon pipeline routes until after

the discovery of oil:

was neither

"(P) rojection of specific pipeline routes

'meaningfully possible,'

under the circumstances."

nor

'reasonably necessary'

The Secretary will be in a much better

position to make a realistic and specific assessment of problems

relating to specific routes when, assuming oil is discovered, the

lessees submit development plans.92

c.

Future Directions of OCS Development

New OCS leasing on a massive scale raises fundamental policy

questions of how the United States should use and develop energy

Unfortunately,

in the next century.

functioned

well

on

OCS

issues

to

the federal

date,

largely

system has not

because

of

a

failure at the federal level to permit state participation in the

decision-making process •

At

least

•

two

.

maJor

structural

problems

control in the current political system.

pure

should

federalism

be

made

concern

of

what

between

federal

0,, r~.r l.cv

vi.-i

resource

The first of these is a

allocation

and

surround

state

of

responsibility

governments.

The

20

problems of federalism with respect to OCS policymaking have been

and

severe,

state

congressional

participation

enactment

of

the

Coastal Zone Management Act.

remains

consistency

inadequate

despite

provisions

of

the

The states must rely on threats to

deny permission for shore facilities

in order to have voice

in

federal planning for OCS development.

This tactic and protracted

litigation are the only available state tools with which to compel

access to the pol icy-making process when the federal level does

not voluntarily solicit or need state views.

The eventual success

of these devices, and consequent extent of state power, depend on

a constitutional clash before the Supreme Court where the results

are uncertain and state influence could be eliminated.

Both the

states and the federal government have vital interests at stake in

OCS development, yet rather than sharing power between federal and

state governments,

the present legal system at best allows

in the courts

states to block plans

instead of

original development of plans l.n the federal

-

system

is

litigation,

the courts will

state

if

Even

unfortunate.

joining

l.n the

agencies. 93

is

power

become politicized

the

This

upheld

in the

.

l.n

resource

field, because they will be the only avenue for the expression of

local interests involved 1.n resource decisions made in Washington.

Some

judicial

participation

in

resource

management

may

be

desirable, but reliance on the judiciary as a standard political

channel

and

as

the

sole

federal plans is unwise.

political

and

are

avenue

of

redress

for

opposition

to

These types of decisions are intensely

laden

with

value

judgments.

Judges

21

are undoubtably capable of making value judgments, but the tradeoffs between environmental concerns and energy considerations are

essentially legislative in nature.

They are policy choices which

will deeply affect the welfare of all Americans and, consequently,

are

not

well

suited

to

statutory

construction

or

case-by-case

development.9 4

In

popular

addition,

political

difficult.

creating

would

relying

input

Litigation

a

far

greater

the

judiciary

makes

tends

checkerboard

make

on

to

of

the

method

coherent

program

focus

individual

on

conflicting

sense

as

if

all

of

development

projects,

adjudications.95

concerned

parties

It

could

participate in a decision such as to rely on nuclear power

for

electrical needs, rather than forcing them to express opposition

to nuclear power as an energy source by bringing suit every time a

reactor is proposed for a particular town.

inconsistent results,

~s

This approach causes

very expensive and does nothing to create

access for members of the public to decisionmaking.

specific

statutory

enactments,

on

the

other

Proceeding by

hand,

would

shift

decisions from the courts into the legislature, where values can

be

balanced

more

freely

and

public

access

will

be

greater.96

Furthermore, enormous amounts of time may be expended in resolving

litigation,

facilities

thereby allowing

inflation to drive

that are eventually constructed.

up

the

Sharing of

cost

of

initial

~

decisionmaking between federal

and state governments would be

more economical and rational way to proceed. 97

0f)1 'lf'}

.

.

f.

a

22

The second major problem with -the present and the proposed

structure of resource

public

to

exercise

decisionmaking.

local

health,

officials,

control

a

is

political

Bureaucrats may

employment

especially

and

given

the

relative

check

have

on

a

resource

much

recreation

the

and

larger

than

inability

develop a long-range energy plan.

inability of

of

the

energy

impact

any

on

elected

legislators

to

Not only is direct guidance

from elected authorities largely absent, but there are few afterthe-fact political controls over many aspects of such bureaucratic

decisionmaking.

The problem of lack of pol icy guidance

is com-

pounded since many areas of resource exploitation are remote and

sparsely populated, if not uninhabited federal reserves.

areas,

there can be no

local

political

In such

check on agency action.

The decision to build a dam or to strip mine may be challenged 1n

the courts, but even if the decision is reversed as violative of

the law or as an abuse of discretion there is no direct sanction

He

for the bureaucrat.

over-exploitation

is

without

free

to err heavily on

risking

more

much

the

than

side of

judicial

challenge to the plan.98

In short,

the underlying problems with OCS development

not really legal or

political.

Their

jurisdictional

solution

at

depends

all,

upon

but

the

are

are

essentially

structuring

of

a

scheme of government for the coastal region that would operate by

political

compromise

rather

than

administrative

hit

and

miss.

23

CONCLUSION

It is too early to tell -whether recent legislative and reguchanges

latory

will

diminish

the

incidence

of

litigated

controversies and facilitate OCS lease administration.

Companies

and concerned

federal

agencies

are

limited

in

their

ability

to

prevent litigation, chiefly because perceptions about how and at

what

rate

the

area

should

difficult to reconcile.

be

developed

remain

disparate

and

Most are agreed that federal leasing of

the OCS requires a balancing of the interests of those seeking to

develop domestic oil and gas resources on an accelerated basis and

those anxious to protect coastal ecosystems and

local

from

Few

the

consequences

of

such

development.

economies

can

agree,

however, on what weight these competing interests should be given

Litigation

and where the balance between them should be struck.

is but

a

manifestation of

this

dichotomy of

Until

vision.

a

measure of consensus exists on these issues, there is no reason to

assume that Atlantic OCS development will proceed free of judicial

.controversy.99

The analysis above shows but one thing

sion which can be

formulated

at

this

time.

there 1s no concluBoth

the

need

for

petroleum and necessity of protecting the environment maintain too

valuable

a

part

between the two.

resulting

failu~e

of

today' s

world

for

this

composer

But if time has told us anything,

to

choose

it is that a

to protect the nation's aquatic frontier during

the current search for energy and

in the decades

tragically despoil the nation's final frontier.

END

001~:. ·

_.,

illo.

•

to

come could

BIBLIOGRAPHY

124 Congressional Record

Marine Mining of the Continental Shelf 1.

Management of Energy Resources on Federal Land 1.

Natural Resources Journal, No. 19.

Oklahoma Law Review, 1977.

Environment Reporter, Vol. 10' 1979.

Reporter, Vol. 12' 1978.

Environment

Environment Reporter, Vol. 9, 1977.

Environment Reporter, Vol. 1 1 ' 1978.

Environment Reporter, Vol. 10, 1980.

Oil on the Sea, Max N. Edwards.

Art. 1, Convention on the Continental Shelf.

Connecticut Law Review, 1979.

Ohio Northern University Law Review, 1977.

United States Constitution.

Stanford Law Review, 1976.

Brooklyn Law Review, 1978.

Ocean Development and International Law Journal, 1980.

Washington Law Review, 1977.

0011~

FOOTNOTES

1.

124 Cong. Rec. 813,994 (daily ed. Aug. 22, 1978) (remarks of

Sen. Jackson).

2.

Dep't of the Interior, Geological Survey, cited in H.R. Rep.

No. 590, 95th Cong., 1st Sess.

71

(1977).

3.

Id. at 74.

4.

43

5.

Convention on the Continental Shelf Article 1, U.N. Doc. A/C.

u.s.c.

13/L.

6.

§ § 1331-1341 (1976).

35 (1958).

Report of the Committee on Energy and Natural Resources on the

Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act Amendments of 1977,

s.

Rep.

No. 284, 95th Cong., 1st Sess. 43 (1977).

13 4 4 ( a )

( S u pp • 1 9 8 0 ) •

7•

43 U • S • C • §

8.

Jones, Mead and Sorenson, The Outer Continental Shelf Lands

Act Amendments of 1978, 19 Nautral Resources Journal 885

(1979).

9.

Executive Office of the President, The National Energy Plan

56 (1977).

10. Id.

1 1 • Id.

12. 19 Natural Resources Journal 886 (1979).

13. Id.

14. Id.

..

,

15. Id.

16. 43

u.s.c.

§

§

-

1334-1337 {1976).

17. 43 C.F.R. Part 3300 {1978).

18. 19 Natural Resources Journal 887 {1979).

19. Id. at 888.

20. 43

21 • Id.

22. 43

u.s.c.A. s

§

1 3 44

{a)

u.s.c.A.

§

1344{a) {Supp. 1979).

{

1) •

1337{a) {1) {Supp. 1979).

23. Id.

24. 43

u.s.c.A. s

1337{a){1){H) {Supp. 1979); 43

u.s.c.A. s

{a){4) {Supp. 1979).

25. Id.

26. Id.

§

1337{a) {Supp. 1979).

27. 19 Natural Resources Journal 918 {1979).

28. 43

u.s.c.A. s

1337 {b) {2) {Supp. 1979).

2 9 • 4 4 I d • § 1 3 3 7 { b ) { 2 ) { B ) { S u pp • 1 9 7 9 ) •

30. 19 Natural Resources Journal 919 {1979).

-31. 43

u.s.c.

1334 {1970).

§

32. Gulf Oil Corp. v. Morton, 493 F.2d 141 {9th Cir. 1973).

33. Union Oil Co. v. Morton, 512 F.2d 743 {9th Cir. 1975).

34. 30 C.F.R.

250.12{c) {1973).

§

35. Id.

36. 512 F.2d 743,

7 50.

-,

~

37. Id. at 7 43 •.

38. Id.

39. Id.

40. Id.

1337

41. Id.

42. 43

u.s.c.

S 1334(a)(1) (1970).

43. 30 C.F.R. S 250.12(2)(c) (1973).

44. The court held that such a taking by interference with private

property rights was within the constitutional power of Congress, subject to payment of compensation. 512 F.2d 743, 751

( 9 th C i r • 1 9 7 5 ) •

45. Id.

46. 43

u.s.c.

§

§

1331-1343 (1976), as amended by OCSLA Amend-

ments of 1978, Pub. No. 95-372, 92 Stat. 629.

47. Id.

§

1340 (c) ( 1 ) •

48. Id.

§

1340 (f) ( 1 ) •

49. Id.

§

1340 (d) •

so.

§

1344 9c) ( 2) •

§

1345 (c) •

Id.

51. Id.

52. Id.

53. Id.

54. Id.

55 • 1 6 U• S • C • A•

§

14 56 ( 3 ) ( S u pp • 1 9 8 0 ) ; 43 U• S • C • A•

§

13 5 1 ( d )

(Supp. 1980).

56. Note, Environmental Law:

Governmental Suspensions of Outer

Continental Shelf Oil Drilling Operations, 1977 Okla. L.

Rev • 9 3 0 , 911 ( 1 9 7 7 ) •

57. Environment Reporter, Volume 10 - Number 16, August 17, 1979,

pp. 1028-9.

58. Id. at 1029.

~ 1 .~,....

0{. I - {·- ... _.

I

59. Id.

60. 19 Natural Resources Journal 891-92 (1979).

61. Environment Reporter, Volume 10 - Number 42, February 15,

1980, p. 2006.

62. 43

u.s.c.

63. Id. at

§

§

§

1301-1315 (1876).

1331-1343.

§

64. United States v. Maine, 420 U.S. 515, 524-26 (1975).

65. Id. at 526-28.

See also Convention on the Continental Shelf

Art. 1, opened for signature April 29, 1953, entered into

force June 10, 1964, 15 U.S.T. 471, T.I.A.S. No. 5578, 499

U.N.T.S. 311.

66. Best, Oil and Gas Operations in the Atlantic Outer Cantinental Shelf:

An Overview of the Regulatory and Litigation -

Related Constraints to Development, 11 Conn. L. Rev. 459,

46 3- 6 4 ( 1 9 7 9 ) •

67. 11 Conn. L. Rev. 465.

68. 16

u.s.c.

§

1451 (h).

69. Id.

70. CZMA,

§

306(c)(8), 16 U.S.C.

1455 (c)(8).

§

71. 11 Conn. L. Rev. 469.

72. Shaffer, OCS Development and the Consistency Provisions of the

Coastal Zone Management Act - Legal and Policy Analysis, 4

OHIO N.U.L. Rev.

597, 601-2- (1977) •

.

73. 16

u.s.c.

•

§

1456(c)(1)-(2).

74. 11 Conn. L. Rev. 470-71.

75. Id.

0(~.1-·

•

)

I

""

:

~~~..)

76. U.S. CONST. art I,

§

8, cl. 3; id. art. VI, cl. 2.

11. 11 Conn. L. Rev. 470-71.

78. Environmental Reporter, Number 10, January 9, 1981.

79. Id.

80. Conservation Law Foundation v. Andrus, 13 ERC 1965.

81. Current Developments, September 28, 1979, p. 1242.

82. Environmental Reporter, Number 10, January 9, 1981.

83. Id.

84. County of Suffolk v. Secretary of the Interior, 562 F.2d 1368

(2d Cir. 1977), cert. denied, 434

u.s. 1064 (1978).

85. Massachusetts v. Andrus, 11 ENVIR. Rep. (BMA) 1138 (D. Mass.

Jan • 2 8 , 19 7 8 ) •

86. American Petroleum Inst. v. Knecht, 456 F. Supp. 889 (C.D.

Cal. 1978).

87. American Petroleum Inst. v. Knecht, 12 ENVIR. Rep. (BNA) 1226

(D.D.C. Sept. 6, 1978).

88. 11 Conn L. Rev. 472.

89. New York v. Kleppe, 9 ENVIR. Rep. (BNA) 1798 (E.D.N.Y. Feb.

17, 1977).

90. 11 Conn. L. Rev. 473.

91. 562 F.2d 1368, 1390.

92. Id. at 1382.

93. Breeden, Federalism and the Development of Outer Continental

•

Shelf Mineral Resources, 28 Stanford L. Rev. 1107, 1145-46

(1976).

94. 28 Stanford L. Rev. 1150-51.

(}f): ,11, ~.

.

"'

95. Id. at 1151.

96. Id. at footnote 198.

97. Id. at 11 51 •

98. Id. at 1152.

99. 11 Conn. L. Rev. 480-81.