Left Behind: The effects of emigration on Salvadoran children, families and communities

advertisement

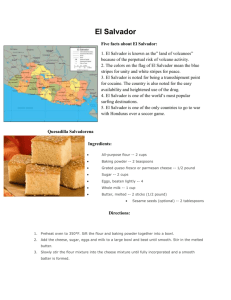

Left Behind: The effects of emigration on Salvadoran children, families and communities Julia Dickson-Gomez Center for AIDS Intervention Research Medical College of Wisconsin Milwaukee, WI Salvadoran Emigration to USA • At least 1 of every 5 Salvadorans resides in the United States (1.1 million)* although estimates range from 13 to 40%** • Over ¼ of all Salvadoran foreign born in the U.S. arrived in 2000 or later* • 4 out of every 5 Salvadoran immigrants were adults of working age. Men outnumber women (52.8 vs. 47.2%)* • Less than half Salvadoran immigrants have finished high school, and 7 out of 10 have limited English proficiency* • There were only 340,000 Salvadoran lawful permanent residents, most achieving this status through family sponsorship* • In spite of the above, Salvadoran immigrant men and women were more likely to participate in the civilian labor force than foreign born men and women overall. In 2008, 90.4% of Salvadoran men 16 and over were participating in the labor force, and 67.5% of the women. *Direccion General de Estadistica y Censos. 2008. VI Censo de Poblacion y de Vivienda, 2007. San Salvador, El Salvador. **United Nations Development Program. 2005. Informe sobre desarrollo humano El Salvador 2005: Una Mirada al Nuevo Nosotros. El Impacto de las Migraciones. San Salvador, UNDP. Effects of Emigration on El Salvador • The Good • Remittances. In 2004, El Salvador received over $2.5 billion based on Central Reserve Bank Estimates, 6 times foreign direct investment • Over one fifth of all households receive remittances • Improves families’ incomes • Improves housing • Ensures children attain higher education • “Retirement fund” for elderly** **United Nations Development Program. 2005. Informe sobre desarrollo humano El Salvador 2005: Una Mirada al Nuevo Nosotros. El Impacto de las Migraciones. San Salvador, UNDP. Effects of Emigration on El Salvador • The Not so Good • Family separation • Separation of spouses and rise in female headed households • Children left in care of extended family • Economic Inequity • At a local level, the differences in standard of living among those receiving remittances and those not may increase feelings of exclusion and social inequality • Rising consumerism • Rising land and housing costs • Salvadorans retiring from construction jobs, often build “replicas” of suburban American homes for retirement • Unmet economic aspirations • Remittances allow young people to achieve higher level of education, but opportunities for work and better pay remain unchanged** • Deportation and Transnational Gangs and Crime • Rises in crime, especially associated with youth gangs (Mara Salvatrucha, 18th Street Gang), drug offenses, armed robbery have been associated in press with “deportees” • Increased drug use, particularly crack since 2000 • El Salvador served as a transshipment point since the 1980s, but drug market opened up in El Salvador as “mules” began to be paid, in part, with cocaine • Crack users in El Salvador, as elsewhere, have heightened HIV risk due to sex for money or drugs exchanges **United Nations Development Program. 2005. Informe sobre desarrollo humano El Salvador 2005: Una Mirada al Nuevo Nosotros. El Impacto de las Migraciones. San Salvador, UNDP. One of Thousands of Shopping Malls One of Our Study Sites Presentation Objectives • To explore the effects of immigration on children “left behind” including drug use, homelessness and HIV risk • To explore the effects of deportation from the U.S. on the individuals deported and their families • To explore the effects of immigration and deportation on communities Methods • Started work in El Salvador in 1996, and in 2001 on HIV risk among crack users • Present analysis based on in-depth and focus group interviews conducted with crack users and non-drug using community residents between June 2006 and March 2010. • 48 in-depth interviews • 6 focus groups with community leaders (members of community directors, religious or non-governmental organization workers) • 3 focus groups with crack users • 420 surveys with active crack users, recruited using Respondent Driven Sampling (RDS) Abandoned • Emotional effects, feeling abandoned • Lack of supervision of young children by extended family, particularly older siblings • Rejection of family due to drug use, stealing things leads to living on street • Homeless crack users at increased risk for HIV • Among our total sample of crack users • • • • • Average of 4 sexual partners in last month 1 in 4 had exchanged sex for crack 1 in 3 had exchanged sex for money Approximately 8 in 10 had unprotected sex in last month HIV prevalence among all participants, (including those who refused a test) was 4.9% [95% CI 2.8%-7.8%] Interviewer: So tell me how often you smoke crack? Jose: When I feel, well I have the following problem. My dad left when I was in 8th grade. He left and after 2 years being there, because he promised me, “When I get there I’m going to send for you.” When he promised me that and got to the States I stopped going to school. I just finished 9th grade and I said to myself, “This coming year, my dad is going to send for me.” The year came and went and he didn’t send for me. He called me by phone and of course he was helping me economically. “Dad, what happened? I’m ready.” “Wait until next year.” Six years came and went with me waiting. In all that time, my best friends were graduating, my sisters, one of my sisters got pregnant, my mother got sick, and I was ignored, always thinking of going to the States. It’s a dream I’ve had since he told me to go to the States… So before I knew it I had made friends with the type of people I had never had before, you know. That’s when I started to smoke cigarettes, when I remembered “My dad lied to me.” [I]n my community nobody knew me as a gang member or an addict, or as a bad person because my dad was very respected in the neighborhood. My dad was one of the ones who led the operatives [during the war], so the people knew me as a good kid from my family, but that was the problem that my dad had lied to me. Interviewer: But now, do you smoke more crack than before or… Jose: “Uh yeah, it’s logical.” Interviewer: How much are you using more or less? Jose: “Because well, you know that when you start with one hit, you feel, it something really strange, you know. “What is this?” But then time goes by, and you start isolating yourself, getting more into that [drugs] and before you know it, you’re already an addict.” Daniel: Since I can remember I’ve been on the streets, like about 25 years living absolutely in the Center of San Salvador, because in my youth, I’m 35, because I lived with my family until 10 years old, and from there I have lived homeless in all the parks, avenues and all the drug selling spots, living, sleeping… Interviewer: What is your relationship with your family like now? Daniel: It’s super deteriorated, because I go to my family and they close the doors on me. I ask them for a little bit of food if only to see if we can have a relationship and they close the doors. What they do is call the police and the police tell me to stay away, that they don’t want to see me because of how I am, indigent, dirty, and also because they say that I come to demand money, like forcing them, and that’s true, but I don’t threaten them. I just go to them because I don’t have any support, only God…but I don’t have the support of anyone in my family. My mother left me when I was one [year old] in this country [to go to the U.S.] and I go to my family to see if I can communicate with her. My siblings have the help of my own mother, but they don’t want to give me any information about her and this makes me feel bad, I feel more sorry for myself and I make more of a mess of my life. Deportations Effects on Families • Crack users whom we interviewed described starting using drugs in the U.S., which often directly or indirectly caused their deportation to the U.S. • These deportees often emigrated to the U.S. when they were very young and, thus, returned to a country they didn’t know, with little family or friends to support them • Feelings of being lost or abandoned upon deportation are compounded by the relative lack and poor quality of drug treatment services in El Salvador Dickson-Gomez, J., Bodnar, G., Guevera, C., Rodriguez, K., Rivas de Mendoza, L. 2011. With God’s Help I Can Do It: Crack Users’ Formal and Informal Recovery Experiences in El Salvador. Substance Use and Misuse. Edwin: I left when I was 11 for the United States, I emigrated, my mom sent for me and there I began my drug addict career in the United States. I tried drugs, crack, marihuana, liquor, and I became very dependent on drugs. Every day I have cravings to use drugs. And so I lost my residency, because of my drug addiction. I lost my job,. I lost my studies. I lost the oportunity to get my U.S. citizenship and everything. Through using drugs I also became a criminal. I began to rob to use drugs because I didn’t have the capacity or the will to work and one day the police caught me. They took everything. They took my residency and they deported me to El Salvador. I’ve been 7 years in San Salvador… Interviewer: So how was it that you came to live on the streets? Was it right after you were deported or were you living somewhere else before? Edwin: [R]eally I had never gone to live on the streets. When they deported me, I had been clean for seven years. I went to a program with a psychiatrist, with a psychologist. I even have a certificate that they gave me for completing the program. But the deportation affected me so much, that I couldn’t stop myself [from using]. I felt without support, without anyone or any help… After 9/11 they passed an anti-terrorist law, so anyone who had crimes like robbery, theft, felonies, fell in the category of deporation, and I was one of them... So my program and probation ended and they decided to deport me and I couldn’t continue with my treatment. I had treatment for 25 years that was going to be paid for by the state of Virginia in Fairfax, so [I lost] the circle that had kept me alive every day, the therapies, the programs and the people…So when I came back deported the first thing that came to my mind was to use drugs… and I started back where I was. I ended up in the streets, with nothing and my family that’s still here said, “No, you’re not coming here to live with us.” They didn’t believe that I had stopped using drugs. My family that’s in the United States had called my family in El Salvador and told them not to open the doors to me and that was another reason I couldn’t resist, my family’s contempt. I told myself, “Well I’m going to keep using drugs since at any rate my family doesn’t love me”…I felt bad and got depressed…and the same depression made me use more and more… and that’s how I ended up on the street. HIV Risk Living in Abandoned Houses or On Street Interviewer: And do you think exchanging sex [while living on the street] could be an HIV risk? Roberto: These last times I was having sex with various indigents that are just crazy, all dirty they look like they’re crazy…and I’ve had to give them a rock and have sex with them these last times. I have a dirty mind because I’ve gone around screwing drunks. When I’m really drunk I have had sex with them and now I’m scared, not because of the question, but because it’s been a number of months, eight months since the last time I had an HIV test and lately I’ve had a lot of sexual relations with men and women. Interviewer: Without protection? Roberto: Without protection and that’s even worse. Without protection. Remesas Interviewer: And what do you do to get money for a rock when you don’t have any errands to run, what do you do to get rock? Jonathon: I lie to them, “Hey look on such and such day they’re going to send money” and the people here know that my family is in the United States, and “Such and such a day they’re going to send money, lend it to me, I’ll pay you back.” Lies, they were lies. That’s what I would do, but I would always do errands or go throw out the trash for them. Interviewer: But so your family has always sent you money. Jonathon: Yes, always, every month they send me 40 or 30 [dollars] Interviewer: And what did you use that money for? Jonathon: For drugs. Remesas Interviewer: To pay for a house or where you lived? Jonathon: No, my family already knows and that’s why they sent me here [to a Ministry for Drug addicts]. They paid for me to be here. They tell me, “Go, Go.” “No, I tell them, “I don’t want to be locked up,” actually it’s more like I tell them “No, I’m fine here.” I don’t have the cravings. The first days I really wanted to get out and use again but not now. Interviewer: But have you ever lived with your family or were you always staying on the street? Jonathon: Just in the street because I didn’t even bathe sometimes and some friends would tell me, “Hey, come here. Do you want to bathe?” I would strip down to my shorts and use a hose. Community Effects of Emigration • Abandoned houses, become “destroyers” (gang houses), “transes” drug houses, or places homeless people squat • Other homes are rented to people whom community residents feel do not have a strong connection to the community as they did not help found it, or were not raised in it • Children left alone or in the care of extended family turn to gang membership and crime • Escalation of crime in neighborhoods contributes to further emigration, along with lack of economic opportunities Why do people leave? Interviewer: Okay, so I want to know if there are people who have left the community here? Ana: They’ve gone because of threats by gang members, they’ve emigrated and they’ve left their houses abandoned. They’re suffering, staying in other parts, leaving behind their little house because they’re afraid they’ll kill them or their children. So we have lots of houses, we have like ten empty houses because the people have gone. Why do people leave? Interviewer: So some people have gone because of threats? What other reasons have people left? Ana: They’ve gone to the United States to better their families, because the truth is that the situation in our country is really. We live in poverty, but I’m going to tell you something, that here maybe we’re rich for other people because I’ve traveled here to el Playon, there are people who live in a terrible poverty. They don’t have anywhere to sleep. They cover themselves with cardboard. So I feel that we’re rich in comparison to things I’ve seen in other communities. People have gone to the United States to see their families get ahead because here, salaries, there isn’t work, well there is, but they pay the people very little and the dollar doesn’t cover expenses. Not at all. And then? Interviewer: And what is it that you have seen that has brought these problems? What are the causes of gangs, drugs, prostitution? Silvia: Look, there are many homes that are broken, the parents, one goes one way, the other goes the other, the children and youth they leave in care of aunts and uncles, in care of grandparents and they don’t have any control over them and now the gangs, any little thing they tell them, “Look, here we’re going to give you such and such, and here you’re going to be good and everything” and they pull them right? And also homes that are established where both parents go to work and they leave early in the morning and don’t get home until night. They don’t have control of their children. We have several here at the school, and it’s a big fight for us when a girl or boy gets in some sort of disciplinary trouble and we send them to call their mom and she’s not there or she works all night and, “No, my mom sleeps all day because she works all night.” And then? Xiomara: And the other thing that has happened is parents going to the United States and leave 3 or 4 children with X person. Those children aren’t controlled by their parents and with those left in charge never mind. They have to work. Those children are left in Silivia: Complete abandonment. Xiomara: Abandonment on the street. So there you start getting to the gang situation, the vices, the lazy people who don’t want to work, don’t want to study. I think that’s the biggest problem in leaving the children alone. Conclusions: Globalization, neoliberal economics and HIV • Globalization has affected the HIV epidemic not only because the virus, drugs and people cross national boundaries. • Global movements of populations disrupts lives, increasing people’s vulnerability to HIV • Strathdee and Patterson*** found that among male IDUs of Mexican descent on the San Diego, Tijuana border those who had been deported were 4 times more likely to be infected than those who had not • Our qualitative research suggests that not only deportation, but also being left behind when family members emigrate causes large social upheavals that put people at risk Cohen, Jon. 2012. San Diego, California and Tijuana, Mexico: My Virus is Your Virus. Science 337(6091):177-178. Conclusions Continued • The root of the problem is North/South inequities. People in El Salvador cannot earn enough to attain the quality of life they desire. • As more people emigrate to the United States, expectations continue to increase. Children are better educated but cannot obtain well paying jobs. Consumerism based on remittances flourishes. • The mass movement of Salvadorans to the U.S. has contributed to crime. • • • U.S. (now multinational) and criminal networks were deported back to El Salvador • Family disruption leaves children with little supervision and feelings of abandonment, making them vulnerable to join gangs • Empty houses are often used by homeless squatters, as gang houses (“destroyers”), or “transes” crack houses Crime and immigration create a vicious cycle where more crime in neighborhoods leads to more emigration which leads to more crime. Decreasing North South disparities may decrease HIV risk and drug use in developing countries like El Salvador.