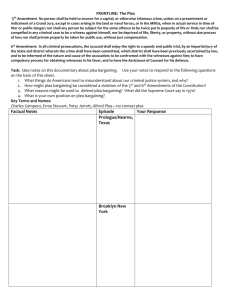

PLEA BARGAINING Paul Stuckle Independent Research Prof. Larkin

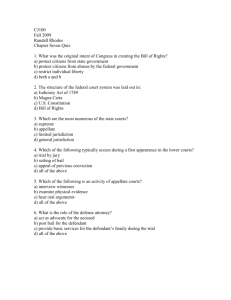

advertisement