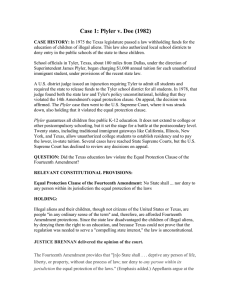

AN ANALYSIS OF THE SUPREME COURT'S DECISION IN

advertisement

AN ANALYSIS OF THE SUPREME COURT'S DECISION IN PLYLER V. DOE AND ITS EFFECT ON BILINGUAL EDUCATION IN THE TEXAS PUBLIC SCHOOLS Introduction In May 1975, the Texas legislature amended Section 21.031 of the Texas Education Code to effectively deny a free public education to children that were not "citizens of the United States or legally admitted aliens.""'" This was accomplished by denying these children 2 the "benefits of the Available School Fund" which in effect with- held state funds from local school districts for the education of these children. The local school districts were allowed to exercise their own discretion by either denying admission to these 3 children or permitting their attendance upon payment of tuition. The con- stitutionality of the statute was challenged by several actions initiated in the United States District Courts of Texas. 4 The case of Doe v. Plyler was instituted m the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas in September of 1977. In November of 1979, several actions were joined together and heard by the United States District Court for the Southern 5 District of Texas as In re Alien Children Education Litigation. Both of these courts found that the Texas statute violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. District Judge Jus- tice, of the Eastern District of Texas, additionally found that the statute was preempted by federal law.6 The United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit found that the statute violated the Equal Protection Clause but determined that there was no basis for the finding of preemption made by the District Court. i oo4to These cases were appealed to the United States Supreme Court, and on June 15, 1982 the court rendered its decision. The Supreme Court handed down a five to four decision, affirming the lower courts * holdings that the statute violated the equal protection g clause. Justice Brennan delivered the opinion of the Court, in 9 which Justices Marshall, Blackmun, Powell and Stevens joined. Jus- tices Marshall, Blackmun and Powell filed concurring opinions."'"0 Chief Justice Burger filed a dissenting 11 opinion in which Justices White, Rehnquist and O'Connor joined. The opinions of the Supreme Court Justices are very interesting and highly elusive. The deci- sion itself is questionable when analyzed by strict constitutional guidelines and may cause severe problems for the Texas public education system. This paper will analyze the Supreme Court's decision and address one such problem. The majority of these undocumented children, children whose presence in the United States is not legal, are prob*ably of limited English proficiency. Thus, possibly requiring the state to provide them with bilingual education. Such a service could add to the State's burdens in providing adequate free public education to all students. A burden which could eventually become devastating to our system of free public education. Analysis of the Supreme Court's Decision Justice Brennan delivered the opinion of the Court, The only issue which the Court addressed was whether the statute. Section 21.031 of the Texas Education Code, violated the equal protection 12 clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Before this issue could be resolved, the Court had to determine if the equal protection clause ii 00411 was even applicable to undocumented aliens found in the United States. The question of whether the equal protection clause protected the rights of undocumented aliens had never been directly consid13 ered by the Court. The relevant part of the Fourteenth Amendment to be considered reads: "nor deny any person within its jurisdic14 tion the equal protection of the laws." The applicability of the equal protection clause to undocumented aliens depended on the proper construction of the words "within its jurisdiction." The State of Texas consistently argued that undocumented aliens were not protected by the equal protection clause because, by virtue of their immigration status they were not persons within the 15 jurisdiction of the State. But each of the lower courts had re- jected this argument and held that undocumented aliens were protected by the equal protection clause in that they must 16 be considered as persons "within the jurisdiction" of the state. The Supreme Court adopted the rationale of the lower courts. The court recognized that the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment had consistently been applied to protect the rights of 17 undocumented aliens. The Court points out that the class of per- sons entitled to protection under the equal protection clause is coextensive with the class to be protected by the due process clause. J. Brennan states that, "both provisions were fashioned to protect 19 an identical class of persons." Chief Justice Burger, in his dissenting opinion, concedes the applicability of the equal protection clause to undocumented aliens when he says: "I have no quarrel with the conclusion that the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment applies to aliens, who, after their illegal entry ii 00412 into this country, are indeed physically "within the jurisdiction" of a State," 20 That the equal protection clause is applicable to undocumented aliens becomes a foregone conclusion when viewed in light of the legislative history behind the Fourteenth Amendment. J, Brennan's opinion points to a statement made by Senator Howard, the floor manager of the Fourteenth Amendment, in the Senate. Senator How^- ard stated: "[t]he last two clauses of the first section of the amendment disable a State from depriving not merely a citizen of the United States, but any person, whoever he may be, . . .the equal 21 protection of the laws of the State." J, Brennan reemphasizes this when he says that, "the protection of the Fourteenth Amendment extends to anyone, citizen or stranger, who is subject to the laws of a State." 22 Very few people would take issue with the conclusion that the equal protection clause should be applicable to all persons found within the borders of the United States. But, such a conclusion 2 -} . . "only begins the inquiry." J The real inquiry centers around the proper test to be applied in determining the constitutionality of Section 21.031 of the Texas Education Code. The issue of the pro- per level of judicial review to be applied in this case was one which J. Brennan's majority opinion very effectively avoids coming to grips with. In the past, the Supreme Court has utilized two standards of review in relation to an equal protection analysis. The first level of judicial review is the rational relationship test. The second, and highest level of review, is referred to as strict scrutiny. ii These tests make up what has been known as the two tiered 00413 model. Up until the 1977-78 Term, the Supreme Court had "never adopted in a majority opinion the use of a standard of review other than the rational relationship or strict scrutiny - compelling 24 interest standards." Beginning with that Term and up to the pre- sent time, the Court has utilized with increasing frequency an 25 intermediate level of review or middle tier. Strict scrutiny is applied "when the governmental act classifies people in terms of their ability to exercise a fundamental right" or "when the governmental classification distinguishes between per26 sons, in any term of any right, upon some 'suspect' basis." If neither of these criterion are involved, then the rational relationship test should be applied. The middle tier of judicial review can best be described as a "balancing test whereby the justices determine whether the burdens placed on individuals by legislative classifications are outweighed by 27 the societal end promoted through the use of the classification." In effect, the Court is asking the question; does the end justify the means? The court has applied this middle tier of judicial review in situations where strict scrutiny was almost applicable, but the requisite criterion were not quite satisfied. Such situations arise where a politically powerless group, or a very important interest is involved. Cases dealing with gender based classifications and illegitimacy have guided us in determining what the Court will consider as a politically powerless group. This case, Plyler v. 28 Doe, may help in determining what the Court will consider as an important, but not quite fundamental, interest which will trigger the intermediate level of judicial scrutiny. ii 00414 Both the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas and the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth circuit determined that strict scrutiny may be applicable to this case. However, neither court applied that level of scrutiny be- cause they determined that the statute could not even pass a rational 29 basis, rational relationship, test. This is contrary to the In re Alien Children court which applied strict scrutiny in determining 30 whether the statute violated the equal protection clause. What should be noted is that each of these lower courts strained to invalidate the statute by using the traditional two tiered model for equal protection analysis. The Supreme Court ignores the standards of review utilized by these lower courts and forges ahead using a standard of review which is never fully described or defined at any point in J. Brennan's opinion. Justice Brennan states that the proper standard of review to be used, "[i]n applying the Equal Protection Clause to most forms of state action," is that standard which seeks "only the assurance that the classification at issue bears some fair relationship to a legi31 timate public purpose." However, he qualifies this statement by saying that the Court would not be faithful to their obligations under the Fourteenth Amendment if they "applied so deferential a 32 standard to every classification." J. Brennan hints at the level of scrutiny which he will apply in this case when he states that under certain circumstances the Court will seek "the assurance that the classification reflects a reasoned judgement consistent with the ideal of equal protection by inquiring whether it may fairly 33 be viewed as furthering a substantial interest of the State." Such circumstances are said to arise when the legislative classification ii 00415 is not "facially invidious" but nevertheless causes "recurring con34 stitutional difficulties," These statements are a very vague allusion to the use of an internmediate level of scrutiny, J, Brennan's approach to the proper level of judicial review appropriate here can only be explained as being result oriented. He probably knew that the use of strict scru- tiny could not be justified and that the statute would most likely pass a rational basis test. The use of an intermediate level of scrutiny was most likely the only way in which a violation of the Equal Protection Clause could be found to exist. The use of such a level of scrutiny was not completely ignored by the lower courts and in fact, probably would have been used by them had there been a precedent set by the Supreme Court sanctioning its use. However, the Supreme Court has never done that and manages to avoid the recognition of such a level of scrutiny here as well, J. Brennan's opinion does not avoid all the criterion connected with the application of the traditional two tiered model, but those that are dealt with are shrouded in terms which leave open the question of when such an intermediate level of scrutiny will be applicable in the future. Judge Justice, in writing for the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas, suggested that undocumented aliens may constitute a suspect class under certain circumstances when he says: Illegal aliens do not constitute a suspect class when they are in violation of state laws or regulations whose underlying purpose is in conformity with a federal objective or end. The issue of their suspectness as a class is raised, however, by the uncontrovertdd history of their abuse and exploitation in certain conditions and circumstances unrelated to the federal base for their exclusion. ii 00416 He then suggests that undocumented aliens should be considered a suspect class, thus requiring strict scrutiny, "in situations where the state acts independently of the federal exclusionary purposes, accepts the presence of illegal aliens, and then subjects them to 36 discriminatory laws." Judge Johnson, writing for the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, also found that, "the characteristics of the group of illegal aliens excluded from benefits 37 under Section 21.031 may be such that suspect status xs proper." The court then goes on to differentiate, just as J. Justice did, between discrimination for permissible and impermissible purposes. J. Johnson states: "we recognize that 'plaintiffs' status as aliens may constitutionally support their exclusion from the governing functions of the states. But we have ascertained no legal precedent for determining that the commission of a federal misdemeanor may in and of itself serve as the legitimate basis for state-imposed disabilities," 3 8 Whereas, the In re Alien Children court seems to reach the conclusion that 39 the class of undocumented aliens is not a suspect class. Justice Brennan rejects the class of undocumented aliens as suspect "because their presence in this country in40 violation of federal law is not a 'constitutional irrelevancy.'" Instead, he focuses on the child's lack of culpability for his status as an illegal alien. Thus differentiating the 41 situation of the undocu- mented child from that of his parents. This is reflected in J. Brennan's statement that, "[e]ven if the State found it expedient to control the conduct of adults by acting against their children, legislation directing the onus of a parent's misconduct against his 42 children does not comport with fundamental conceptions of justice." s 00417 This one statement reflects that these undocumented children are somehow a class within a class which is due a separate and higher level of scrutiny than their parents. It also reemphasizes the Court's result oriented approach to this case, in that it reflects a reliance on traditional concepts of justice and not strict constitutional standards for the analysis of the issues, A differentiation between the status of the parent and that of the child and a reliance on natural justice theories to justify the use of a heightened level of scrutiny can be found in each of the lower courts' opinions as well. J, Justice stated that, "[w]hile the undocumented minor plaintiffs are of course legally culpable and subject to deportation, they can hardly be held morally responsible . for their presence here." 43 J. Johnson agrees with .this. principle when he says, "[t]he plaintiffs undeniably stand in violation of 44 federal law, but certainly they have committed no moral wrong," The In re Alien Children court gives a good explanation of the level of scrutiny that should be applied in such situations when it writes: "[c]ases involving classifications which punish children for acts committed by their parents are not subject to strict judicial scrutiny. They nevertheless are invalid if they are not substantially related to a permissible state interest. . . .The 45 legislative means as well as the ends are subject to examination." Justice Powell, in his concurring opinion, follows this line of thought by stating that the "classification at issue deprives a group of children of the opportunity for education afforded all other children simply because they have been assigned a legal status due to a violation of law by their parents,"^6 J, Powell analogizes the status of these undocumented alien children to that of ii 418 illegitimates. This analogy is totally unsuppoartable in that ille^ gitimacy is an immutable characteristic whereas the characteristic of being undocumented is not. This line of thought completely ignores the plain and straight forward language of the federal law which vests upon these undocu^ mented aliens their illegal status. The statute reads: "[a]ny alien who (1) enters the United States at any time or place other than as designated by immigration officers, or (2) eludes examination or inspection by immigration officers. , .shall. . .be guilty of a mis47 demeanor." The statute makes no differentiation between aliens on the basis of age and requires absolutely no form of culpability to be guilty of its violation. Chief Justice Burger, in his dissenting opinion, attacks this form of rationale by saying that, "the Equal Protection Clause does not preclude legislators from classifying among persons on the basis of factors and characteristics over which individuals may be said to 48 lack 'control.'" He attacks the majority opinion for its improper construction of the federal immigration laws when he states: "[ille- gality of presence in the United States does not - and need not depend on some amorphous concept of 'guilt11 or 'innocence' concerning 49 an alien's entry." C. J. Burger then goes on to say that, "a State's use of federal immigration status as a basis for legislative classification is not necessarily rendered suspect for its failure 50 to take such factors into account." C. J. Burger also attacks J. Powell's analogy to illegitimate children when he says: "[t]he state has not thrust any disabilities upon appellees due to their 'status of birth.' Rather, appellees' status is predicated upon the 51 circumstances of their concededly illegal presence m this country." In fact, J1. Brennan recognizes that "undocumented status" is not "an absolutely immutable characteristic since it is the product of conscious, indeed unlawful, action." 52 Following an examination of the type of classification involved, J. Brennan focuses on the nature of the right involved. His majority . . . 53 opinion rejects classifying education as a fundamental right. However, he goes to great lengths to describe the unique and invaluable role that education plays in our modern society. He recognizes that education "has a fundamental role in maintaining the fabric of our 54 society." He argues that even though education, may be a form of "governmental 'benefit'" it is still distinguishable "from other forms of social welfare legislation." 55 J. Brennan's opinion and each of the lower courts' opinions depend, to a certain extent, on San Antonio 56 Independent School District v. Rodriguez in determining the nature of education as a right and the proper level of scrutiny to be applied. The Rodriguez court was faced with a constitutional challenge to the Texas system of financing public education. The true thrust of the case was an attack on the State's fiscal policies and not on its system of public education, as is involved here. The plaintiffs, appellees', in Rodriguez, had argued that strict scrutiny should be applied in determining whether the system of school financing violated the Equal Protection Clause. However, J. Powell, in his majority opinion, utilized a rational basis test on the theory that, "[w]hatever merit appellee's argument might have if a State's financing system occassioned an absolute denial of educational opportunities to any of its children, that argument provides no basis for finding an interference with fundamental rights where only relative differences m spending levels are involved." 5 7 In Rodriguez, there was no basis ii 00420 for finding that the system failed "to provide each child with an opportunity to acquire the basic minimal skills necessary for the enjoyment of the rights of speech and of full participation in the 58 political process." The plaintiffs there had argued that educa- tion should be a fundamental right because it was "essential to the effective exercise of First Amendment 59 freedoms and to intelligent utilization of the right to vote." The lower courts here, focused on the language, in J, Powell's opinion, which suggested that the Rodriguez court was making no determination of the proper level of scrutiny to be applied where an "absolute denial of educational opportunities" might exist. Judge Justice recognized that the Rodriguez "opinion is conspicuous in its efforts not to foreclose strict scrutiny in response to constitutional /- n challenges to absolute deprivation of educational opportunity." J. Johnson, of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, focuses on the unique aspect of this case when he says, "education has yet to be classified as a fundamental interest sufficient to invoke strict scrutiny under the equal protection clause; but neither this Court nor the Supreme Court has ever been faced with a statute absolutely barring some resident children from all access to free public education." fi 9 Both of these courts determined that such an absolute deprivation of the right to an education may require a 63 heightened form of judicial review. The In re Alien Children court, on the other hand, found that 64 "strict judicial scrutiny should be applied." The court went on to state: The bases for this conclusion are the following: the statute absolutely deprives undocumented children of access to education thereby causing them, great harm; there is a direct and substantial relationship between education and the explicity guaranteed right to exchange ideas and information; and the provision of education is not a social or economic policy but a state function. In its conclusion, the court states; "access to education is a fundamental right . Because access to a free public education was the major issue in these cases, the United States District Courts both found that the policy of some school districts, of charging tuition to undocumented aliens, was a form of discrimination on the basis of 67 wealth. However, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals never addressed this issue, therefore it was never reached by the Supreme Court either. Justice Brennan*s opinion mainly relies on the fact that education plays such an invaluable role in our society and that its denial causes such enormous hardships to justify the use of a heightened form of scrutiny. He points to the fact that, "[b]y denying these children a basic education, we deny them the ability to live within the structure of our civic institutions, and foreclose any realistic possibility that they will contribute in even the smallest way to the progress of our Nation." 6 8 In light of this unique, though not fundamental, right, J. Brennan announced the test that would be used "[i]n determining the rationality of "Section 21.031." 69 He believed that the Court should "take into account" the "costs to the Nation and to the innocent children who are" the vic70 tims of such a statute. He stated that by considering "these countervailing costs, the discrimination contained in" Section 21.031 "can hardly be considered71rational unless it furthers some substantial goal of the State." Though J. Brennan speaks in terms of the 51 "rationality" of the statute, he adds to this the furthering of 72 some "substantial goal." In the application of this level of review, it is hard to tell the difference between his substantial goal and the traditional compelling interest standard. But the standard of review itself, is one which the concurring Justices agree with. Justice Marshall in his concurring opinion, agrees with the use of a standard of review which employs "an approach that allows for varying levels of scrutiny depending upon 'the constitutional and societal importance of the interest adversely affected and the recognized invidiousness of 73the basis upon which the particular classification is drawn.'" He disagreed with the majority opinion in that he believes "that an individual's interest in education is fundamental." 74 Justice Blackmun's concurring opinion agrees with the requirement that the State come forward with "something more than a rational 75 basis" to justify the statute. He adopts the rational of the Rod- riguez court that "it is not the province of this Court to create substantive constitutional *7 £ rights in the name of guaranteeing equal protection of the laws." Then he seems to violate this precept by equating the right to an education with the right to vote, thus making education an 77 "extraordinary right" due the same level of scrutiny as voting. J. Blackmun points to the fact that the denial 78 of either of these rights creates a "discrete underclass." He states that, "denial of an education is the analogue of denial of the right to vote: the former relegates the individual to second- class social status; the latter places him at a permanent political disadvantage." 79 ii 00423 Justice Blackmun justifies his analysis of the right to an 80 education as being "fully consistent with Rodriguez." The only person who could really say whether or not this is a valid statement is J. Powell, and he does an excellent job of ignoring the issue. He completely avoids the issue of the nature of the right involved and centers his concurring opinion around the type of classification drawn by the statute. J. Powell finds an analogy between the status of these undocumented alien children and 81 that of illegitimates, thus requiring a heightened form of review. He states that "[a] legis- lative classification that threatens the creation of an underclass of future citizens and residents cannot be reconciled with one of 82 the fundamental purposes of the Fourteenth Amendment." J. Powell states that the proper level of review to be applied is one which requires "that the State's interest be substantial and that 8the means 3 bear a "fair and substantial relation" to those interests." Chief Justice Burger, in his dissenting opinion, attacks the level of scrutiny used by the Court by saying that "[i]f ever a court was guilty of an unabashedly result-oriented approach, this case is 84 a prime example." He recognized that, "[t]he importance of educa85 tion is beyond dispute" but, then goes on to say that "the impor- tance of a governmental service does not elevate it to the status 8 of 6 a "fundamental right" for purposes of equal protection analysis." The Chief Justice points to J. Powell's opinion in the Rodriguez case, in condemning the use of an intermediate level of scrutiny, where J. Powell states, "to the extent this Court raises or lowers the degree of 'judicial scrutiny'1 in equal protection cases according to a transient Court majority's view of the societal importance of the interest affected, we 'assume a legislative role and one for 87 which the Court lacks both authority and competence.' " He suggests that a rational basis test should have been used here when he says, "our inquiry should focus on and be limited to whether the legislative classification at 8 issue bears a rational relationship to a legi8 timate state purpose." He believes that the level of judicial review applied in this case should not have been affected by the fact that the right involved is "access to public education - as opposed to legislation allocating other important government benefits, such 89 as public assistance, health care, or housing." Instead the Court patches "together bits and pieces of what might be termed quasisuspect-class and quasi-fundamental-rights analysis, 90"arid spins out a theory custom-tailored to the facts" of this case. The lower courts, in the Plyler case, found that Section 21.031 of the Texas Education Code failed to pass a rational basis test. The State attempted to prove that by accepting these undocumented children into the school system and educating than, the citizens and legally admitted children of the State suffered a detrimental impact. The primary purpose of the statute was to "employ public educational funds to provide education to United States citizens and legally 92 admitted aliens." However, J. Justice determined that the fact that "a law saves money" is "not sufficient justification" for pas93 sing a rational basis test. He then goes on to say that, "the states' adoption of a federal criterion, in this case the illegality of the child's presence in the United States, in itself," does not "provide a rational justification for differential treatment by the 94 state." The reason for this is that "while distinctions in immi- gration status legitimate bases for federal they 95 J. classification, are normally of are no concern to the states." Justice found that 91 the Texas statute did not "propose to serve any federal purposes" nor was there any "truly rational connection between the ends 96 sought and the means employed." He believed that the exclusion of "illegal immigrant children because of" the problems which educating them creates, "is both irrational, because the undocumented children as a class are basically indistinguishable from the legally resident alien children in terms of their needs, 9 7and ineffectual, because the dominant problem remains unsolved." Thus, "[b]y vir- tue of its lack of 98 rationality" the statute "violates the equal protection clause." Judge Johnson, of the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, determined that "if illegal aliens are granted free education, legal aliens 99 and citizens will not be absolutely deprived of a free education." In fact, the only true effect will be a decline in the quality of education "and a mere decline in the quality of education that falls equally on the entire population does not give rise to a claim of constitutional dimension."''"00 He goes on to say that, "a states' desire to save money cannot be the basis of the total exclusion from public schools of a group of persons who are entitled to the equal protection of the laws of Texas and who share similar characteristics 101 with included children." The In re Alien Children court found that Texas had failed to show that "excluding children from school is in any way necessary 102 to the improvement of the education in the state." The court then uses the State's arguments in Rodriguez to rebut its arguments here when it refers to the fact that Texas argued in Rodriguez, that there was "no evidence that the quality of education is 103 somehow strictly tied to the amount of money expended on each child." ii 00426 However, they now wish "the court to assume without any credible supporting evidence that a proportionately small diminution of the funds spent on each child will have a grave impact on the quality of education.""'"0^ The State of Texas also asserted that the statute had an additional goal of lessening the incentives for the entrance of aliens into the United States. J. Johnson found that the means used to accomplish such a goal, which is "entirely consistent with federal 105 immigration policy," must "be rationally related to that goal." J. Justice found that the statute did not have "either the purpose or the effect of keeping illegal aliens out of the State of Texas.""'"06 J. Johnson found that, "the statute is not rationally related to its asserted goal" because 107 it was not the most effective means of accomplishmg that goal. The In re Alien Children court, on the other hand, found that such a goal was an impermissible one because, "[m]easures intended to increase or decrease immigration, whether legal or 108 illegal, are the province of the federal government." Chief Justice Burger's dissent found that the statute does pass a rational basis test. He observes that the primary conten- tion of the State is that Section 21.031 "serves to prevent undue depletion of its limited revenues available for education, and to preserve the fiscal integrity of the State's school 109 financing system against an ever-increasing flood of illegal aliens." He goes on to say that, "such fiscal concerns alone could not justify discrimination against a suspect class or an arbitrary 110 and irrational denial of benefits to a particular group of persons." However, the "prudent conservation of finite state revenues is" not 'Jper se an illegitimate goal." 111 ii The Chief Justice concludes that, "it simply is 00427 not 'irrational' for a State to conclude that it does not have the same responsibility to provide benefits for persons whose very presence in the State and this country is illegal as it does to pro112 vide for persons lawfully present." Because of the fact that "illegal aliens have no right whatever to be here. . .the State may reasonably, and constitutionally, elect not to provide them with governmental services at the expense of those who are lawfully in 113 the State." Chief Justice Burger points out that, "the federal government has seen fit to exclude illegal aliens from numerous social welfare programs" and that such exclusions "tend to support the rationality of excluding illegal alien residents of a State from such programs so as to preserve the State's finite revenues for the benefit of lawful residents.""*""^ He goes on to say that the funds saved by enforcing this statute could be used "to 'improve the quality of education* in the public school system, or to enhance the funds available for other social programs, or to reduce the tax burden placed on its residents," 115 and that each of these uses would constitute a legitimate purpose. Therefore, according to the Chief Justice, the statute should be able to pass a rational basis test. However, the majority of the Court felt that the application of such a test, under these circumstances, was totally improper. Justice Brennan, in applying an intermediate level of judicial review, first attacked the argument that "the undocumented status of these children" in and of itself was "a sufficient rational basis for denying them benefits that a State might choose to afford other 116 residents." ii tection He recognized that when dealing with an equal pro- 00428 issue, the courts should "be attentive to congressional policy." 117 However, in his analysis he was "unable to find in the congressional immigration scheme any statement of policy that might weigh significantly" in favor of "the States" authority to deprive these children of an education." 118 J. Brennan finds "no indication that the disability imposed by "Section 21.031 "corresponds to any 119 identifiable congressional policy." In fact, "the classification reflected in 'the statute' does not operate harmoniously within the 120 federal program." He bases this conclusion on the theory that the State has no way of knowing which, if any, of these undocumented children "will in fact be deported until after deportation proceedings have been completed" therefore, it is "difficult for the State to justify a denial of education to a child enjoying an inchoate 121 federal permission to remain." J. Brennan then goes on to say that the only way the State can justify its use of undocumented status "as a criterion for its own discriminatory policy," is if they can "demonstrate that the classification is reasonably 122 adapted to "the purposes for which the state desires to use it." At this point, the Court has reached the ultimate issue presented by the case. As C. J. Burger terms it: "[t]he dispositive issue. . . is whether, for purposes of allocating its finite resources, a State has a legitimate reason to differentiate between persons who are law123 fully within the State and those who are unlawfully there." fore, the analysis at this point has two steps to it. There- The Court must first determine if the conservation of limited state funds is a legitimate goal. Then, if it is, whether or not the classification is reasonably related to that goal. The Court recognizes that the State's main argument is that the major purpose of the statute is "the preservation of the state's 20 00429 limited resources for the education of its lawful residents." 124 Both J. Blackmun and J. Powell found that the statute was not sup125 ported by or related to any substantial state interest. J. Bren- nan 's majority opinion completely ignores the issue of whether or not the conservation of a state's limited financial resources for education is a legitimate interest. One can only assume that he deems it be a legitimate interest, because he goes directly to an analysis of "three colorable 126 state interests that might" justify the classification used. However, his use of these three cate- gories is itself confusing because he uses the term "state interest" to describe them. If we take J. Brennan at his word, then he fails to even address the ultimate issue of whether the classification used by the statute is rationally related to the state's interest. The first interest that J. Brennan attacks is that of protecting 127 "the State from an influx of illegal immigrants." To discredit this State interest he states that Section 21.031 "hardly offers an effective method of dealing with an urgent demographic or economic problem." 128 He then goes on to say that the evidence in the record failed to show "that illegal entrants impose any significant burdens 129 on the State's economy." This is a totally ridiculous statement in light of J. Brennan*s very own majority opinion in De Canas v. 130 Bica, or possibly J. Brennan is suggesting that the effect that illegal immigrants have on the Texas' economy is different from that which it has on California's economy. His analysis here suggests nothing more than the fact that the statute is not the most effective method of achieving the state interest. The second interest J. Brennan addressed is the contention by the State that "undocumented children are appropriately singled out for exclusion because of the special burdens they impose on the 131 State's abxlxty to provxde hxgh qualxty publxc educatxon." He attacks this assertion by pointing out that "the record in no way supports the claim that exclusion of undocumented children 132 is likely to improve the overall quality of education xn the State." J. Brennan ignores the issue. Again, The asserted state interest is conser- vation of limited financial resources for education, not the improvement of the quality of public education. J. Brennan goes on to say that where "educational cost and need" are concerned "undocumented children are 'basically indistinguishable' from legally resident 133 alien children." This statement xs basxcally true except for one factor, sheer numbers. The number of undocumented aliens in the State is for all practical purposes indeterminable. Therefore the effect, on a state's limited financial resources, of a judicial mandate to educate these undocumented children is itself indeterminable. The final interest put forth by the State is the assertion that the undocumented children's "unlawful presence within the United States renders them less likely than other children to remain within the boundaries of the State, and to put their 134 education to productive social or political use within the State." In layxng to rest this final argument, J. Brennan concludes that Texas "has no assurance that any child, citizen or not, will employ the education pro135 vided by the State within the confines of the State's borders." However, the fact remains that if the federal government vigorously enforced its immigration laws, these children would not be in the State at all, and thus there would be no need to educate them. Justice Brennan concludes his opinion by stating that for Texas to be able "to deny a discrete group of innocent children the (10431 free public education that it offers to other children residing within its borders, that denial must be justified by a showing that it furthers some substantial state interest. 1 No such showing was made o/- here." This is J. Brennan's conclusion in spite of the fact that he never addresses the ultimate issue of whether or not the conservation of a state's limited financial resources is a legitimate, much less a substantial, state interest. Justice Brennan's majority opinion can only be described as a constitutional absurdity. However, this statement in itself may avoid the real question, which is; was the decision right. The answer to this question has to be yes, the decision of the Court was right. By strict constitutional standards, the decision was an unquestionably wrong one, but when one weighs the detrimental cost of not educating these children against the benefits gained, the conclusion is unavoidable, that the decision of the Court was a proper one. Even C. J. Burger recognizes this fact in his dissenting opinion when he states: "[d]enying a free education to illegal alien children is not a choice I would make were I a legislator. Apart from compassionate considerations, the long-range costs of excluding any children from the public schools may well outweigh the 137 costs of educating them." The Court found that, "many of the undocumented children disabled by this classification will remain in this country indefinitely, and that some will become lawful residents or citizens of the United States." 138 Most undocumented Mexican immigrants are young, single males. It has also been determined that "most undocumented Mexican 139 immigrants remain in the U.S. for less than one year." The wives ii 00432 51 and children, of those undocumented aliens that are married, are rarely brought along "due to the increased risk of detection by U.S. authorities and to the higher cost of supporting them in this country." 1 4 0 However, those that do bring their families along remain in this country an avaerge of 6.5 years and, in excess of, 90 percent of these undocumented aliens plan to establish the United States as their permanent residence and eventually become naturalized citizens.141 In the initial Plyler case, J. Justice made a finding of fact that the families that were represented in the suit had "lived in the city 142 of Tyler for a period of three to thirteen years." An additional finding made was that each of these families included "at least one child, not of school age, who is a citizen of the 143 United States by virtue of his or her birth xn the United States." Undocumented alien children comprise a relatively small portion of the total undocumented alien population. Studies reveal that less than three percent of the undocumented Mexican immigrants which have been interviewed, "report ever having children in U.S. public 144 schools." However, any statistics available concerning undocumented aliens are totally unverifiable. In fact, "because of the clandestine nature of the unlawful resident population, any efforts to measure 14 5 their numbers are fraught wxth great uncertainty." This is due to the fact that "it is unrealistic to expect unlawful residents to cooperate fully in an interview dealing with their legal status." 146 However, whatever their numbers may be, the Court's decision here forces the states to accept the duty of educating them, a duty which has been ignored for too long. It is a duty to insure that every member of our society is able to operate harmoniously within it by 00433These possessing a certain minimal level of skills. children are here and most likely, are here to stay. Therefore, they must be allowed to gain those skills necessary to make a meaningful contribution to our society. Such skills are primarily gained, by any child, through our nation's public education system. The Decision^ Affect On Bilingual Education in the Texas Public Schools Texas has the second highest concentration of legally admitted, permanent resident aliens from Mexico. number of resident aliens. Only California has a greater The education of the children of Mexican immigrants carries with it significant problems. One of these prob- lems is the effective education of these students. The vast majority 147 of immigrant students are of limited English-speaking ability. Therefore, their education requires more than the normal school curriculum. One study indicates that possibly148 40 percent have a very limited or no English-speaking ability. The effect of this recent Supreme Court decision will manifest itself in an increase in the number of children, with limited Englishspeaking ability, to enroll in Texas public schools. Estimates of the number of undocumented 149 alien children presently in Texas range from 10,000 to 111,000. The disparity between these two figures is due to the clandestine nature of the illegal alien population within our borders. The proper figure probably lies somewhere in between, but a dependence on any statistical analysis in the area of undocumented aliens is a highly risky proposition. The actual number of school age undocumented aliens is not totally irrelevant, but at this point, it makes little difference what the actual numbers are. Each and every one of these children are entitled to a free public education, if they are residents of ii 00434 Texas. Not all of these children can even be expected to show up and register in the public schools. ably not register. In fact, a majority will prob- Their parents will still fear the specter of deportation, and others will probably not care to avail themselves of such a free education. However, some will register, and the num- ber that does will probably not be insubstantial. Those who do show up to register, will add to the number of "students of limited English proficiency" already enrolled in Texas public schools. 150 151 The Texas Bilingual Education Act was passed in 19 73. The purpose of the Act is to "insure equal educational opportunity to every student" by establishing "bilingual 152 education and special language programs in the public schools." However, the opening sentence of the act makes clear that, "[ejnglish is the basic language 153 of the State of Texas." So that the main thrust of the Act is to meet the needs of these students with limited English proficiency 154 "and facilitate their integration into the regular school curriculum. Section 21.452 of the Texas Bilingual Education Act defines "students of limited English proficiency" as "students whose primary language is other than English and whose English language skills are such that the 155 students have difficulty performing ordinary classwork in English." The great majority of undocumented alien chil- dren entering the Texas public school system will fall within this definition, therefore, increasing the need for bilingual and special language programs in the public schools. The institution of a bilin- gual education program is triggered when a school district "has an enrollment of 20 or more 156 students of limited English proficiency in the same grade level." The increased need for bilingual and spe- cial language programs will put a strain on two resources. ii 00435 The first being financial resources and the second is the limited number of teachers qualified to teach bilingual programs. For Texas, the financial problem will be the easiest to overcome. State and local funds provide 90 percent of the funding for the public schools. The state's general fund, primarily made up of revenues from consumer taxes, provides funds to the local school districts on the basis of average daily attendance. Therefore, as the number of students enrolled rises, so will the state funding. Local funds, derived from the local property tax, provides about 4 5 157 percent of the funds. This amount does not rise as the student population rises. The majority of Mexican immigrants are concentrated in the counties bordering Mexico. in Texas. These are among the poorest school districts Because of the low socioeconomic status of these Mexican immigrants, they have a very limited "ability to improve local economies 158 and to accumulate taxable property wealth." Thus, they do little to increase the available local funds for public education. The federal government provides 45 percent of the funds available for bilingual education. 159 The State provides some funds, a little more than $50 per student of limited English proficiency, i fio but the majority of the balance is provided for by local funds. Therefore, the majority of the expense in providing bilingual education falls on the local school districts. Because the majority of these immigrants are located in the poorer school districts, this expense falls on the districts least capable of providing the needed funds. ^ ^ These financial problems are compounded by the course that the current administration has taken towards all social programs. ii 00436 The current "administration has proposed reductions in educational fund162 ing of about 37 percent." Allocations for bilingual education were cut by 9.1 percent in the 1982-83 school year. An additional cut of 16 percent, from the 1982-83 level of funding, has been pro163 posed for the 1983-84 school year. Dallas is a good example of how these funding cuts effect a district's bilingual education program. For the 1981-82 school year, the Dallas area received $1,518,562 bilingual education. vious year's funding. in federal funds for This was an 8.4 percent increase over the preIn the 19 82-83 school year $1,105,934 in federal funds, they received a decrease of $412,628 or 27 percent. The proposed allocation for the 1983-84 school year is $929,000. This is a decrease of 38.8 percent over 164 a two year period, just in the area of bilingual education. In spite of the fact that Texas is one of the most financialy stable states in the United States, its local school districts will be hard pressed for the funds needed to institute these bilingual programs. The real threat to the education of these children is the lack of qualified teachers available to teach bilingual and special language programs. A 19 76-77 study revealed that there were "34,000 teachers nationwide who were minimally qualified to teach in a bilingual education program" compared to an "estimated 3.6 million chil165 dren nationwide" in need of such programs. teacher ratio of 105 to 1. This xs a student to Because the concentration of students in need of such programs is in relatively poorer school districts, teachers salaries are lower, and therefore the incentive to achieve bilingual certification is negligible. There is simply no real finan- cial reward to be gained from being a bilingual teacher. ii 00437 The State recognizes only one base pay and increments scale for all teachers. 166 However, the State does recognize emergency situations where a lack of qualified teachers may exist thus requiring "the hiring of teaching personnel on a bilingual emergency permit." 16 7 The current, Texas bilingual education laws are the result of 168 United States v. State of Texas, a suit brought in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Texas. J. Justice again got an opportunity to attack the education laws of Texas, two years after his decision in Plyler. The court found that the Texas system of bilingual education was a violation of the equal protec169 tion clause, Title VI and the Equal Educational Opportunity Act. Even before the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals could review this decision, Texas chnaged its bilingual education laws. The.Court of Appeals reversed the lower court and remanded the case, but it didn't matter, Texas had already conceded defeat and changed its laws. 170 The Court of Appeals found that these new Texas laws con171 formed to federal guidelines. Therefore, the Texas bilingual education laws would probably pass any further constitutional or statutory challenge. Thus, there is little question that the Texas bilingual education system is not only non-discriminatory but comprehensive in scope and potentially effective. The only question remaining concerns whether or not it can effectively be implemented to educate these undocumented alien children. The major problem will be in training a sufficient number of teachers to meet the burden of educating these children. Conclusion For many reasons, the Supreme Court's decision can be considered as the proper one. ii The best reason is that "it is senseless 00438 for an enlightened society to deprive any children - including illegal 172 aliens - of an elementary education." Such a deprivation puts these children at a "severe disadvantage in both realizing their own personal potential and in their productivecontribution to society and 173 to the communities in which they reside." However, the closeness of the decision indicates that Texas may have won had they been able to justify the statute as furthering a substantial state interest. Texas had a difficult time in merely justifying the passage of the statute, much less proving a substantial state interest. Even before the statute was passed, Texas "never attempted to examine 174 the impact of undocumented children on the schools." Before Sec- tion 21.031 was amended to exclude undocumented aliens, John Hill, Attorney General of Texas, issued an opinion which indicated that illegal alien children were probably entitled to the benefit of free 175 public education. the statute. In spite of this, the Texas legislature amended The In re Alien Children court could not even uncover 27 ^ the legislative history behind the amendment, if one in fact existed. By passing this amendment in the manner in which they did, Texas really bit off more than it could chew. tion which it could not support. The State adopted a posi- However, even though some of the blame can be attributed to Texas, a great deal of it should rest on the shoulders of the federal government. Because in handing down this decision, "[t]he Court makes no attempt to disguise that it is acting to make up for Congress' lack of 'effective leadership' in dealing with the serious national problems caused by the influx 177 of uncountable millions of illegal aliens across our borders." Each of the courts involved in this litigation, accuse the 00409 State of relegating these children to the status of a second-class individual by denying them an education. However, it is not the State which places them in such a sub-class status, it is the federal government which does this. The federal government is responsible for the very existence of these undocumented aliens within our borders. 178 Once the alien has crossed over our borders, most will 179 "enjoy a form of de facto amnesty." The problem of illegal entry by Mexican aliens is one which is increasing at an alarming rate. In 1979, "over one million illegal entrants were apprehended and reliable sources within the Border Patrol estimate that 180 for every illegal alien caught, two or three slipped through." J. Powell recognized that the statefe '^responsibility, if any, for the influx of aliens is slight compared 181 to that imposed by the Constitution on the federal government." Therefore, the federal government's refusal to deal with the problem, in itself, relegates undocumented aliens to a sub-class status. A refusal to act not only encourages illegal entry into this country, it also encourages the exploitation of these undocumented aliens as a source of cheap labor. The Court itself recognizes that the major "incentive for ille182 gal entry into" this country "is the availability of employment." In a 1972-73 study of documented Mexican immigrants, 49.9 percent of those interview, said that work, wages, and better living 183 conditions were their primary reasons for coming to this country. It should be pointed out that the same study revealed that 9.7 percent came here to receive better educational opportunities for themselves 184 and their children. Therefore, considering Mexico's rapidly deteriorating economy, the number of illegal aliens in this country can only be expected to rise in the future. 00440 In 1976 there were an estimated 1,789,500 school age children of limited English proficiency in the United States. By the year 2000, this number is expected to increase to 2,630,000. This is an increase of 46.9 percent, and these figures are only for children of Spanish background. 18 5 The education of these children is a problem which has not totally been ignored by Congress, Congress has enacted the Bilingual Education Act which attempts to deal with 18 6 the problem. However, as a whole, our nation has really failed to come to grips with the bilingual education problem. The problem of bilingual education reflects this nation's overall "deficiency in foreign language skills. in fact, "[f]ew- er than four percent of our public high school graduates have more than two years of foreign language study." 188 Such figures could present a "very real threat to our national security and our econo189 mic health." In the areas of industry and commerce alone, an inability to speak other than the mother tongue can create serious problems. There is a real "need to be able to converse freely on general everyday topics, to be able to understand what is said between foreigners at conferences, and to be able to mix socially 190 with foreign businessmen." national in scope . Thus, our nation's problem is inter- Likewise, this nation's problem with the educating of illegal alien children is one shared by almost all Western nations. All of the Western European nations enjoy the benefits of some form of immigrant workers. It has been determined that "[o]ne prob- lem common to all the Western European receiving countries is school191 ing." In Switzerland, France, and Germany, school attendance by an immigrant worker's children is compulsory. The trend in these European schools is192towards1 the use of the native tongue in educating them. 0 0children's 441 32 It has commonly been recognized that education and training are critical to the economic advancement of immigrant children. However, the degree to which the school system is open and responsive to the needs of immigrant children depends on the political pressure that the immigrant whoker can exert on their behalf.193 Thus, "[o]ne of the key distinctions between migrant labor in the U.S. 294 and in Europe lies xn the lack of any specific social provisions. Instead of dealing with the problem of illegal immigrants, our federal government chooses to ignore it. Congress most likely ignores the plight of illegal aliens because it is a very touchy political issue. rich nation. Mexico is now an oil Mexico also acts as a political buffer zone between the United States and radical Central American countries. Mexico is a nation whose friendship we need. In short, If Congress acts too aggressively towards the problem, our nationte relationship with Mexico could be jeopardized. Add to this the fact that a large majority of the employers of these illegal aliens have very strong political lobbies. Because it is a rather volatile political issue. Congress has chosen to ignore it; thereby, laying the ground work and providing the incentive for the Supreme Court's decision. The Court's decision "rests on such a unique confluence of theories and rationales that it will likely stand for little beyond" 195 the result in this particular case. The Court finds that edu- cation is not a fundamental right and that illegal aliens are not a suspect class. The Court determines that a state cannot deny a free public education to illegal alien children. by the Court is the real question mark in the case. The test used The Court tells us "little more than that the level of scrutiny employed to strike ii 00442 down the Texas law applies only when illegal alien children are 196 deprived of a public education." However, the Court would prob- ably subject any statute, which deprives an undocumented alien child of a social benefit, to the same level of scrutiny, if the social benefit was the type of benefit which all other children were entitled to receive. To prove this, the test used by the Court has to be subjected to two hypothetical situations. First, let us suppose that the right involved is the same, but the class being denied that right is different. If illegal aliens were immediately deported upon their discovery in this country, then undeniably their children, whether citizens or not, would have to be deported with them. If such laws were vigorously enforced, then the class's connection between itself and any right to a social benefit, whether or not a fundamental right, would be so tenuous as to be nonexistent, thereby justifying the denial of an education to them. Now let us suppose that the class remains the same, undocumented alien children enjoying a de facto form of amnesty, but the social benefit changes. If the social benefit were one which all other children were entitled to, it would be impossible to prove that the class of undocumented alien children was somehow less deserving of the benefit. In this situation, a violation of the equal protection clause could be found. If this decision stands for anything, it stands for the proposition that the Court will no longer be tied down by substantive constitutional law standards where sensitive social issues are involved. That whenever the issue justifies its use, the inter- mediate level of scrutiny will be used to scrutinize the issues of 00443 a case. The Court does not say when such a level of scrutiny should be used because it will not know itself until the issue faces them. It was properly used here to declare a particularly discriminatory statute unconstitutional. The decision was a proper one. 35 00444 FOOTNOTES 1. Tex. Educ. Code Ann. §21.031 (Vernon Supp. 1982). 2. Id. 3. In re Alien Children Education Litigation, 501 F. Supp. 544 (S.D. Tex. 1980) . 4. 458 F. Supp. 569 (E.D. Tex. 1978). 5. 501 F. Supp. 544 (S.D. Tex. 1980). 6. 458 F. Supp. at 584. 7. Doe v. Plyler, 628 F.2nd 448, 454 (5th Cir. 1980). 8. Plyler v. Doe, 102 S. Ct. 2382 (1982). 9. Id. at 2388. 10. 102 S, Ct. 2382, 2402 (1982) (Marshall, J., concurring); 102 S. Ct. 2382, 2402 (1982) (Blackmun, J., concurring); 102 S. Ct. 2382, 2405 (1982) (Powell, J., concurring). 11. 102 S. Ct. 2382, 2408 (1982) (Burger, C. J., dissenting). 12. 102 S. Ct. at 2388. 13. 501 F. Supp. at 567. 14. U. S. Const, amend. XIV, §1. 15. 628 F.2d at 454; 501 F. Supp. at 568; 458 F. Supp. at 579. 16. Id. 17. 102 S. Ct. at 2391. 18. Id at 2392. 19. Id. 20. Id at 2409. 21. Id at 2393-2394. 22. Id at 2394. 23. Id. 00445 Footnotes - 2 24. J. Nowak, R. Rotunda, J. Young, Constitutional Law, at 522-527, ~526~ (19 78 )T 25. Id at 526. 26. Id at 524. 27. Id at 526. 28. 102 S. Ct. 2382 (1982) . 29. 628 F.2d at 458; 458 F. Supp. at 585. 30. 501 F. Supp. at 564. 31. 102 S. Ct. at 2394. 32. Id. 33. Id at 2395. 34. Id. 35. 458 F. Supp. at 583. 36. Id. 37. 628 F.2d at 458. 38 . Id. 39. 501 F. Supp. at 565. 40. 102 S. Ct. at 2398. 41. Id at 2396. 42. Id. 43. 458 F. Supp. at 582. 44. 628 F.2d at 457. 45. 501 F. Supp. at 573. 46. 102 S. Ct. at 2406. 47. 8 U.S.C. §1325 (1977) . 48. 102 S. Ct. at 2409. 49. Id at 2410. 50. Id. 00446 Footnotes - 8 51. Id. 52. Id at 2396-2397. 53. Id at 2398. 54. Id at 2397. 55. Id. 56. 411 U.S. 1 (1973). 57. Id at 37. 58. Id. 59. Id at 35. 60. Id at 37. 61. 458 F. Supp. at 580. 62. 628 F.2d at 456. 63. 628 F.2d at 457; 458 F. Supp. at 580. 64. 501 F. Supp. at 564. 65. Id. 66. Id at 597. 67. 501 F. Supp. at 570; 458 F. Supp. at 581. 68. 102 S. Ct. at 2398. 69. Id. 70. Id. 71. Id. 72. Id. 73. Id at 2402. 74. Id. 75. Id at 2404. 76. Id at 2403. 77. Id. 78. Id at 2404. 00447 Footnotes - 8 80. Id. 81. Id at 2406. 82. Id. 83. Id. 84. Id at 2409. 85. Id at 2411. 86. Id. r- 88. Id. Id- 90. Id at 2409. 91. 458 F. Supp. at 573 92. Id at 575. 93. Id at 586. 94. Id. 95. Id at 587. 96. Id at 588. 97. Id at 589. UD 00 t • Id. 00 • Id. CP) CO 79. Id at 593. 99. 628 F. 2d at 459. 100. Id. 101. Id. 102. 501 F. Supp. at 583 103. Id. 104. Id. 105. 628 F. 2d at 460. 106. 4 58 F. Supp. at 575 00448 Footnotes - 8 107. 628 F.2d at 461. 108. 501 F. Supp. at 578. 109. 102 S. Ct. at 2411. 110. Id at 2411-2412. 111. Id at 2412. 112. Id. 113. Id. 114. Id at 2413. 115. Id. 116. Id at 2398. 117. Id at 2399. 118. Id. 119. Id. 120. Id. 121. Id at 2399-2400. 122. Id at 2400. 123. Id at 2409. 124. Id at 2400. 125. Id at 2405, 2406-2407. 126. Id at 2400. 127. Id. 128. Id at 2400-2401. 129. Id at 2400-2401. 130. 96 S. Ct. 933 (1976) . 131. 102 S. Ct. at 2401. 132. Id. 133. Id. 134. Id. 00449 Footnotes - 8 135. Id. 136. Id at 2402. 137. Id at 2413-2414. 138. Id at 2401. 139. J. Rock, The Impact of Mexican Immigration on the Texas Public School System at 66-67 (May 1980) (Professional Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin). 140. Id at 66. 141. Id at 68. 142. 458 F. Supp. at 574. 143. Id. 144. J. Rock, supra note 139, at 67. 14 5. 1980 Census: Counting Illegal Aliens: Hearings on S.2366 Before the Subcomm. on Energy, Nuclear proliferation and Federal Services of the senate Comm. on Governmental Affairs, 96th Cong., 2d Sess. 67 (1980) (statement of Vincent P. Barabba, Director, Bureau of the Census). 146. Id. 147. J. Rock, supra note 139, at 52. 148. Id. 149. Id at 65. 150. Tex. Educ. Code Ann. §21.451 (Vernon Supp. 1982). 151. Id. 152. Id. 153. Id. 154. Id. 155. Tex. Educ. Code Ann. §21.4 52 (Vernon Supp. 1982). 156. Tex. Educ. Code Ann. §21.453 (c) (Vernon Supp. 1982). 157. J. Rock, supra note 139, at 39. 158. Id at 21. 00450 Footnotes - 8 159. 458 F. Supp. at 577. 160. Tex. Educ. Code Ann. §21.460(a) (Vernon Supp. 1982). 161. J. Rock, supra note 139, at 46. 162. Budget Issues for Fiscal Year 1983: Hearings Before the House Comm. on the Budget, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 387 (1982) (Analysis of the Effect of the FY82 and FY83 Reagan Budget Proposals on Urban Schools). .. 163. Id at 393. 164. Id at 397. 165. Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, Education and Reilated Agencies Appropriations for Fiscal Year 1982 : Hearings Before a Subcomm. of the Senate Comm. on Appropriations, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. 130 (1982) (statement of Gilbert Chavez, Acting Director of the Office of Bilingual Education and Minority Language Affairs). 166. Tex. Educ. Code Ann. §21.459(d) (Vernon Supp. 1982). 167. Tex. Educ. Code Ann. §21.4 53(h) (Vernon Supp. 1982). 168. 506 F. Supp. 405 (E.D. Tex. 1981). 169. Id. 170. United States v. State of Texas, 680 F.2d 356 (5th Cir. 1982). 171. Id at 374. 172. 102 S. Ct. at 2408. 173. J. Rock, supra note 139, at 71. 174. 501 F. Supp. at 583. 175. Tex. Atty' Gen. Op. No. H-586 (1975). 176. 501 F. Supp. at 555 n. 19. 177. 102 S. Ct. at 2408. 178. J. Rock, supra note 139, at 66. 179. 501 F. Supp. at 559. 180. 1980 Census: Counting Illegal Aliens:, supra note 145, at 35 (statement of Senator Huddleston). 00451 Footnotes - 8 181. 102 S. Ct. at 2407. 182. Id at 2401. 183. J. Rock, supra note 139, at 10. 184. Id. 185. Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations for 1983: Hearings Before a Subcomm. of the House Comm. on Appropriations, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. 936 (1982) (Projections of Non-English Language Background and Limited English Proficient Persons in the United States to the Year 2000). 186. Bilingual Education Act, 20 U.S.C. §3221 (1981). 18 7. National Security and Economic Growth Through Foreign Language Improvement: Hearings on H.R. 3231 Before the Subcomm. on Postsecondary Education of the House Comm. on Education And Labor, 97th Cong., 1st Sess. 1 (1981) (opening statement of Paul Simon, Representative of Illinois, chairman of the subcomm.). 188. Id. 189. Id. 190. V. Mallinson, The Western European Idea in Education 360 71980) . 191. J. Power, Migrant Workers in Western Europe and the United States 99 Tl979). ~~ 192. ~~ ~~ M. Miller, P. Martin, Administering Foreign-Worker Programs 76 71982). - ~~ 193. M. Piore, Birds of Passage 109 (1979). 194. J. Power, supra note 191, at 104. 195. 102 S. Ct. at 2408-2409. 196. Id at 2409. 00452 ~

![The UNC Policy Manual 700.1.4[G] Adopted 11/12/2004 Amended 07/01/07](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/012014973_1-6dab9e811fb276e7cbea93f611ad7cd8-300x300.png)