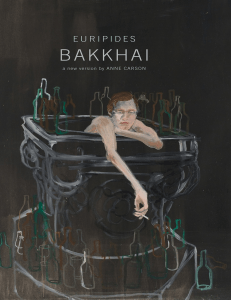

The Bacchae EN302: European Theatre

advertisement

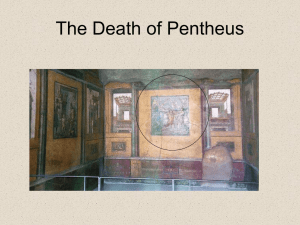

The Bacchae EN302: European Theatre Euripides (c.480-406 BC) • Wrote 92 plays, of which 19 survive • Often revisionist • Political and religious scepticism • Rarely won first prize • Prosecuted (unsuccessfully) for impiety • Fled Athens towards the end of his life The Bacchae • • • • • First performed 405 BC (posthumously) Uneasy combination of tragic and comic elements Peloponnesian War: Athens under siege (until 404 BC) Euripides had used drama to critique war (Women of Troy) Athens’ defeat in 404 BC brought the ‘golden age’ of tragedy (and democracy) to an end Dionysos • Dionysos’ birth (twice born) • Zeus’ ‘male womb’ • Half human (‘My daughter had a son who’s now a god’, p. 377) • Ambiguous identity: • both foreign and Greek • androgynous • deceptive • Representation of wildness, irrationality, impulse? Dionysos • God of wine • Wine and theatre: • Tiresias says it ‘stops grief’: ‘How else could we ease the ache of living?’ (p. 381) • The thyrsos: • Fennel/pine/ivy • Symbol of fertility and abundance Images of Dionysos Images of Dionysos Images of Dionysos Images of Dionysos Dionysos worship • Oreibasia (nighttime mountain dancing, drinking) • Sparagmos (tearing apart of animal) • Omophagia (eating of raw flesh) • Surrender of self: ekstasis (‘standing outside of ourselves’) • ‘I’ll run them / wild with ecstasy!’ (p. 372) • ‘Participation mystique’? • Coined by French ethnologist Lucien Lévy-Bruhl and made famous by Jung, this term describes a state of mind in which no differentiation is made between the self and things outside the self. Dionysos worship in The Bacchae • Never seen, only described • By Dionysos, pp. 370-2: • ‘barbarian joy’, ‘battle’, ‘suffer’, revenge • By Chorus, pp. 375-6: • ‘sweet’, ‘joy’, ecstasy • By Pentheus (imagined throughout): • ‘lewd’, ‘lusty’ (p. 379 – though Tiresias refutes this) • By Herdsman, pp. 397-401: • ‘so strange, so horrible’, ‘great holy cry’, ‘eerie’, monstrous, miraculous, graphic violence • sexual undercurrent? Dionysos worship in The Bacchae • The thyrsos in The Bacchae: • ‘armed them all with my green fennel wand – in battle it’s an ivied spear’ (p. 370) • ‘Guard the violence in your green wand, / respect its holy power’ (p. 374) • At one point, all on stage hold it (Chorus, Tiresias, Kadmos) – Pentheus is the only one without. • He grabs Dionysos’ own thyrsos later… The Apollonian and the Dionysian • From Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy (1872) • Apollonian: form, structure, control, rational thought, reason, beauty, protection from the Dionysian • Dionysian: wildness, irrationality, intoxication, loss of self, animalism, sexuality, lust, cruelty • Nietzsche describes Euripides as ‘a poet who fought throughout his long life against Dionysus with heroic force – only to conclude his life with a glorification of his opponent…’ The Apollonian and the Dionysian • City vs. mountain • Pentheus and the repressed Dionysian: • Pentheus’ descriptions of Dionysos: ‘the stranger with the girlish body’ (p. 383); • cutting of Dionysos’ curls; • Dionysos’ tucking back of Pentheus’ curls later • Pentheus draws attention to choice between order and chaos: ‘When I come out, I’ll either be fighting, or I’ll put myself in your hands.’ (p. 405) • Chorus: ‘A reckless mouth and a mad / defiant mind / ruin a man – / but restraint and good sense / protect him’ (p. 384) • Tiresias shows appropriate balance of Apollonian and Dionysian? He is Apollo’s prophet, but worships Dionysos equally… The Bacchae and the feminine • Bacchae as representatives of unrestrained femininity (compare Furies/Clytemnestra)? • Only women induced to madness in the play • ‘We are humiliated / when we let women act like this’ (p. 4012) • Think about male-dominated audience Music and the Dionysian • Music is the most Dionysian of the arts, according to Nietzsche • Choral odes • Chorus equate dancing with music, wine and joy / ekstasis • Ritual element to repetition • Suggestion that chorus are drumming (p. 391) Dionysos and the theatre • Theatre of Dionysos • Tiresias on Dionysos: ‘his future power throughout Greece will be vast’ (p. 381) • Chorus as Dionysos-worshippers, calling audience to join in: • they bless those who ‘give body and soul to Bacchus’ (p. 373) • they condemn Pentheus • Voice of Dionysos calling (probably singing) from within stage building: • Supernatural frisson? • Literal invocation? • Special effects? • Acting as ritual / transubstantiation Communitas • From the work of anthropologist Victor Turner (1920-83) • Intense feelings of solidarity and togetherness amongst members of a group of people: ‘a direct, immediate and total confrontation of human identities’ (1969: 132) • ‘Spontaneous communitas has something “magical” about it. Subjectively there is in it the feeling of endless power. … It is almost everywhere held to be sacred or “holy,” possibly because it transgresses or dissolves the norms that govern structured and institutionalised relationships and is accompanied by experiences of unprecedented potency.’ (1969: 128-39) Turner, V. W. (1969) The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure, New York: Aldine. Communitas, ritual and performance • Three phases in a rite of passage: separation, transition (‘limen’), and incorporation (‘reaggregation’) • In liminality, argues Turner, ‘people “play” with the elements of the familiar and defamiliarise them’ (1982: 27), and where it is ‘socially positive’, • ‘it presents, directly or by implication, a model of human society as a homogenous, unstructured communitas, whose boundaries are ideally coterminous with those of the human species. When even two people believe they experience unity, all people are felt by those two, even if only for a flash, to be one.’ (1982: 47) Turner, V. W. (1982) From Ritual to Theatre: The Human Seriousness of Play, New York: PAJ. A sceptical undercurrent? • Dangers of loss of self / ekstasis? • Second messenger describes ‘One hand / made of thousands’ contributing to Pentheus’ death (p. 416); • Agave is ‘empty’ and ‘senseless’, ‘totally possessed by Bakkhos’ (p. 417) • Cynical presentation of worship? • Tiresias (in Bacchic garb): ‘You won’t hear me asking which gods exist / or cross-examining their actions. … The wisest man living, though he brings / to bear his keenest logic, / will never break their grip on our lives.’ (p. 378) • Kadmos’s advice to Pentheus to lie: ‘Suppose it’s true / that Bakkhos is no real god – / proclaim him one. It’s a fine distinguished lie!’ (p. 382) • Messenger: ‘The best wisdom is knowing what the gods want’ (p. 418) – how easy is this? Audience’s sympathies? • Is the chorus’ viewpoint a model for ours? • Do we approve of their bloodlust? • Do we share their rejoicing in the revelation of Pentheus’ death? • Appearance of Agave late in the play: • Chorus express pity for her (‘poor woman’, p. 420) and for Kadmos (p. 427) • Pentheus’ hamartia, Agave’s anagnorisis? • Agave ends by rejecting Dionysos Dionysos: a capricious god? • Chorus’ presentation of Dionysos as peace-loving: a god who ‘makes men rich / and saves the young men’s lives’ (p. 386). • He says he’s there to teach: ‘this town must learn to perfection / all my mysteries have to teach’ (p. 371) • Does Dionysos manipulate Pentheus into committing blasphemy? • Dionysos’ evident enjoyment of irony: • ‘it could be your face to which the blood will come’ • ‘You’ll make me go all to pieces!’ ‘I’d have it no other way’ (p. 410) • Smiling mask throughout play • Cruel? • Terrifying? • Unknowable? • Kadmos recognises Dionysos: ‘You are / Vengeance – without feeling or limit’ (p. 429).