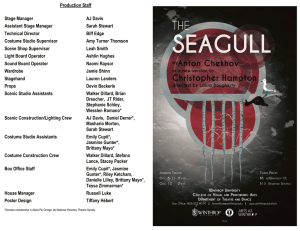

The Seagull Anton Chekhov

Chekhov

The Seagull

Anton

Anton

Chekhov

1860-1904

5 Things to know about Chekhov

1.

Upbringing/ Family:

Father was pious, sincere, simple, abusive and violent; Anton would be none of these things. Father’s cruelty ‘had cast a pall on his childhood and aroused in his soul a protest against the despotic imposition of belief’

2. What he wrote of his birthplace might be true of the world of The Seagull: ‘[The] inhabitants do nothing but eat, drink, reproduce, and have no other interests. The town’s location is beautiful in all respects, a splendid climate, masses of fruits of the earth, but the inhabitants are hellishly inert. Everyone is musical, gifted with imagination, highly strung, sensitive, but it’s all wasted.’ (Dorn’s diagnosis: ‘How

nervous

they all are’)

Taganrog, Moscow, Sakhalin

3.

‘Literature is my mistress, medicine my lawful wife.’

From a successful author who’s /

Managed to combine and fuse /

A soul at peace, a mind on fire, /

The enema tube and poet’s lyre.

(inscription, 1889)

Honed his acute powers of observation as a Medical student in the dissecting theatre

4. In 1896, his fame was almost entirely based on his short story writing; three full-length plays written – and only one performed – before The

Seagull:

Fatherloss (lost); Ivanov;

The Wood Demon

(unperformed; to be reworked into Uncle

Vanya)

The trip to Sakhalin 1890:

‘Sakhalin is the only place where criminal colonization can be studied…

I’d say that places like Sakhalin should be visited for homage, as Turks go to Mecca… We have rotted alive millions of people, rotted them for nothing, without thinking, barbarically. (p.220)

Trip took 81 days. Once there, he collected data on 10,000 inhabitants.

Can you imagine it – I am writing a play which I shall probably not finish before the end of

November. I am writing it not without pleasure, though I swear fearfully at the conventions of the stage. It’s a comedy, there are three women’s parts, six men’s, four acts, landscapes (view over the lake); a great deal of conversation about literature, little action, tons of love.

Letter August 1895.

What kind of play is The

Seagull?

It’s a comedy, there are three women’s parts, six men’s, four acts,

[…] little action […] tons of love.

‘Four acts’: Acts 1-3 =

A Month in the

Country; 2 exterior, 1 interior. Summer

Act IV: 2 years later: interior, Autumn,

An ensemble piece

‘Tons of love’: An unending and irreparable daisy chain of desire: nobody loves

Medvedenko, who loves

Masha who loves

Konstantin who loves

Nina who loves Trigorin who loves her and

Arkadina. Dorn loves noone in particular, but is loved by all.

‘Landscap es

(views over the

Spring Flood (1897)

‘a great deal of conversation about literature…’

This is the most intertextual, theatrically self-reflexive of Chekhov’s plays

HAUNTED BY HAMLET

Reference to Hamlet in Act 1 may have been prompted by censor’s objections to play:

Potapenko wrote to Chekhov:

It opens with a quotation from Maupassant’s Bel-

Ami (challenge for actors?); Act 1 proceeds quickly to play-within-play

‘The whole trouble is that your decadent has a lax attitude to his mother’s love life, which the censor’s rules don’t allow. You’ll have to insert a scene from Hamlet:

‘A bloody deed! Almost as bad, good mother/ As kill a king and marry with his brother’… Actually, we’ll get out of it more easily.’

Ivan Turgenev (1818-83)

, the greatest short story writer of the generation before

Chekhov’s, is almost a character in the play.

TRIGORIN: When I’m dead my friends will say as they pass my grave: ‘There lies Trigorin.

He was a good writer, but he wasn’t as good as Turgenev.’

(PS> Nabokov wrote Turgenev "is not a great writer, though a pleasant one", and ranked him fourth among nineteenthcentury Russian prose writers, behind Tolstoy, Gogol, and

CHEKHOV. )

As a teenager, Chekhov advised his brothers to read Turgenev’s lecture

‘Hamlet and Don

Quixote’ – vision of human beings torn between solipsism/scepticism of

Hamlet and generous optimism of Don

Quixote.

‘New forms…’

Rules of the Drama as pronounced to a friend in summer 1889:

Things on stage should be as complicated yet as simple as in life. People dine, just dine, while their happiness is made and their lives are smashed. If in Act 1 you have a pistol hanging on the wall, then it must fire in the last act. There’s nothing harder than to write a good farce. (p.203 Rayfield, Anton

Chekhov: A Life)

The theatre should be like the church: the same for the peasant and the general… (1891: p.239)

Always claimed that he was unable to see any merit in Ibsen – The Wild

Duck , a reference point (perhaps parodic) for The Seagull he described as ‘tired, boring and weak’ (p.547)

‘Whoever invents new endings for plays will open a new era. The damned endings won’t come! The hero either gets married or shoots himself.’ (Letter to Suvorin, 4 June

1892; p.270)

In The Seagull traditions are reversed. All the materials of comedy are there – couples in love, youth against age – but the action resolves uncomically. No happy reunions: age survives, youth is destroyed: like Hedda Gabler, it ends with an offstage gunshot and an inadequate coda.

In Act 4, Trigorin wants to revisit the scene of the play in Act 1 to inspire a short story. But he has already scripted the play, as it were: at the end of Act 2:

An idea for a short story. A girl like you, living beside a lake since she was a child. She loves the lake the way a seagull might – she’s as happy and free as a seagull. But one day by chance a man comes along and sees her. And quite idly destroys her, like the seagull.

NINA: I am the seagull. – she has been reduced to the status of a manipulated character in Trigorin’s fiction; she is a victim of aestheticization.

Life into Art

Chekhov, like Trigorin, saw his life as raw material for The Seagull:

Hunting incident with painter Levitan:

‘One fine lovelorn creature less, and two fools go home to supper’

Like Trigorin, Chekhov was gifted a medallion by admirer: Lidia Avilova inscribed it with title, page and line number of one of Chekhov’s books.

Chekhov duly found the reference in his story ‘Neighbours’:

‘If you ever need my life, come and take it’.

Multiple self-portraits: elements of

Chekhov’s character and experience in all three major male roles: Dr Dorn,

Konstantin, Trigorin.

Art and Life

Kostya’s semi-epiphany in his soliloquy in Act 4:

Yes, I’m coming more and more to the conclusion that its not a question of forms, old or new, but of writing without thought to any forms at all – writing because it flows freely our of your heart.

(p.117)

In 1894, Anton had written to Lika:

‘Not for a minute am I free of the thought that I must, am obliged to write.

Write, write and write.’

(p.315 Rayfield)

Premiere: Aleksandrinski Theatre, St Petersburg,

October 1896

Sarah Bernhardt outdated acting styles; repertoire of French farce; inexperienced director, first performance a benefit night for Levkeeva an actress who would find in Arkadina only a satire on her own career.

The director was using sets meant for bourgeois farces and quite unsuited to scenes in a dilapidated country estate

Anton: ‘the actors don’t know their parts. They understand nothing. Their acting is horrible.’

First night was a scandal. In the playwithin-the-play, you could hear open laughter, loud conversations, sometimes hissing.

Eyewitness: the audience was somehow spiteful, they were saying ‘The devil knows what this is, boredom, decadence, you wouldn’t watch it if it were free.’

Chekhov wrote to his brother

Misha: ‘The play has flopped and failed sensationally. There was a heavy tension of misunderstanding and disgrace in the theatre. The acting was abominable, stupid. The moral is: don’t write plays’ (399)

I have no luck with the theatre, such awful luck that if I married an actress we would probably beget an orang utan or a porcupine’ (480)

Things improved a little with subsequent handful of performances; but this was a bitter blow to Chekhov’s fledgling career as playwright.

Early Reception: Decadence and

Depression

Sazanova, friend of Suvorin, read in Dec 1895 and anticipated public opinion:

‘I read The Seagull. A thoroughly depressing impression. In literature only Chekhov, in music Chopin make that impression on me, like a stone on your soul, you can’t breathe. It is unrelieved gloom. (Rayfield 355)

Chekhov read the play out loud to a group in Moscow in the same month. One of those present recorded:

‘I remember the impression the play made. It was like

Arkadina’s reaction to Treplev’s play: “Decadence!”

“New forms?” … I remember the argument, the noise…

Korsh’s amazement: “Dear boy, that’s bad theatre: you have a man shoot himself off-stage and don’t even let him speak before he dies!’ etc. I remember Chekhov’s face, half embarrassed, half stern.’ (Rayfield 355)

Vasili Nemirovich-Danchenko

(brother of Vladimir who would mount the great production at

Moscow Arts Theatre) wrote to his brother of the disastrous premiere at the Aleksandrinski Theatre, St

Petersburg: “This isn’t a play. There is nothing theatrical in it. I think

Chekhov is dead for stage. .. The auditorium expected something great and got a bad, boring piece.”

(457)

The Moscow Arts Theatre production: December 1898

After the disaster at the Aleksandrinksy in Petersburg, Chekhov had to be persuaded to give his blessing to the Moscow production planned by

Nemirovich…

Nemirovich to Chekhov, April 25 1898:

The Seagull enthralls me and I will stake anything you like that these hidden dramas and tragedies in every single character of the play, given a skilful, extremely conscientious production without banalities, can enthrall the auditorium too. […] Our theatre is beginning to arouse the strong indignation of the Imperial theatres. They understand we are making war on routine, clichés, recognized geniuses and so on. (15-6)

Nemirovich to Chekhov, May 12 1898:

The Seagull is the only contemporary play that excites me as a director and you are the only contemporary writer who presents any great interest for a theatre with an educational repertoire. (16)

The Process:

Nemirovich to Chekhov, May 31 1898:

I am going through The Seagull and keep trying to find those little bridges over which a director must take his audience and lead them away from their beloved routine. Audiences still can’t (and maybe never will) surrender to the mood of the play: it must be put over very firmly. (18)

Nemirovich to Chekhov, August 24, 1898:

We are at the planning stage, trying out the tones or rather the half-tones in which The Seagull must be done

[…] I have never been so in love with your talent as I am now, when I have had occasion to go to the very heart of your play. (32)

Nemirovich to Stanislavski (on receiving the latter’s plans for the first three acts), September 2, 1898:

The Seagull is written in delicate pencil and demands, in my view, great care in the staging. There are passages which could easily create an awkward impression. I should take out anything which disposes the audience to unnecessary laughter so that they may be ready to receive the best passages in the play. So, for example, during the performance of Treplev’s play, the rest of the cast should not act full out. Otherwise it will all too easily for the house to focus on the onstage audience rather than on Treplev and Nina. At that point Treplev and Nina’s tense, decadent, somber mood must dominate the frivolous mood of the other characters.

Let’s take for example the ‘croaking frogs’ during the performance of Treplev’s play. I want precisely the opposite, total enigmatic silence. […] There are times when it is inappropriate to distract the audience’s attention, titillate it with some detail of everyday life.

Audiences are always stupid.

You have to treat them like children.

Nemirovich & Stanislavski:

A representative disagreement

(80 hours of rehearsal over 24 sessions; 9 with Stanislavski, 15 with Nemirovich

Stanislavski to Nemirovich, September

10, 1898:

I put frogs in during the play scene to create total quiet. Quiet is conveyed in the theatre not by silence but by noise. [...] I chose frogs partly because I possess an instrument which imitates them convincingly. Besides, it seems to me that a soliloquy, which deals with animals, is more effective with living creatures calling the background. Perhaps I am wrong.

[…] You know and feel Chekhov better and more strongly than I.

Characterization, detail and the war against cliché:

After Chekhov had seen his play for the first time in the Moscow Arts production in a command performance (audience = 10), he visited Stanislavski in his dressing room:

‘Scold me, Anton Pavlovich,’ I begged him.

‘Wonderful! Listen, it was wonderful! Only you need torn shoes and check trousers.’

He would tell me no more. What did he mean? […] Trigorin was a young writer, a favourite of the women – and suddenly he was to wear torn shoes and checked trousers! I played the part in the most elegant of costumes – white trousers, white vest, white hat, slippers, and a handsome make-up.

A year or more passed. Again I played the part of Trigorin [….] and during one of the performances I suddenly understood what Chekhov had meant.

Of course, the shoes must be torn and the trousers checked, and Trigorin must not be handsome. In this lies the salt of the part: for young inexperienced girls it is important that a man should be a writer and print touching and sentimental romances, and the Ninas, one after the other, will throw themselves on his neck, without noticing that he is not talented, that he is not handsome, that he wears checked trousers and torn shoes. Only afterwards, when the love affairs with such ‘seagulls’ is over, do they begin to understand that it was girlish imagination which created the great genius in their heads, instead of a simple mediocrity. Again, the depth and the richness of Chekhov’s laconic remark struck me. It was very typical and characteristic of him.

Stanislavski, My Life in Art, pp.358-9

On first acquaintance with Chekhov’s “Seagull” I did not understand the essence, the aroma, the beauty of the his play. I wrote the mise-en-scene , and still did not understand, although, unknown to myself, I had apparently felt its substance. When I directed the play [no mention of Nemirovich!] I still did not understand it. (My Life in Art,

352)

The Success:

Chekhov to Dr Ivan Iordanov, September 21, 1898:

If you should happen to be in Moscow, then go to the Hermitage Theatre where

Stanislavski and Nemirovich-Danchenko are putting on plays. The mise-en-scene is outstanding, nothing like it has been seen in Russia. Among other things they are doing my ill-fated Seagull…

Nemirovich to Chekhov (after the ‘colossal’ success of the opening night), December 18-21, 1898:

You will gather all the reasons for such joy: the artists were in love with the play and each rehearsal revealed ever new artistic pearls in it. At the same time we feared the public, little versed in literature, with little culture, corrupted by cheap stage effects, not accustomed to extreme artistic simplicity, would not appreciate the beauty of The Seagull.

[…] The audience not only grasped the general mood, not only the story, which in this play was so difficult to register as the unifying factor, but also every idea which you created as both artist and thinker, everything got across and was grasped.

Knipper – wonderful, ideal Arkadina. She got so deep into the part that she lost nothing of the actressy elegance, the beautiful frocks, the enchanting vulgarity, the meanness, etc.

[…]

PS. Can we have Uncle Vanya?

Marya Chehkova to Chekhov, December 18, 1898:

The staging was beautiful […] Stanislavski played

Trigorin limply and the Seagull is a bad actress, but in general the staging is so lifelike that you completely forget that it’s a stage. There was silence in the theatre, people listened attentively.

When in 1902, the company moved into its own building an emblematic seagull was sewn into the front curtain as the theatre’s symbol.

Chekhov married his

Arkadina in

Actresses are cows who think they are goddesses…

Machiavellis in skirts… (1888)

http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=YfOW3vvWLrg

TONAL VARIATION: extract from the dialogue between Arkadina (Kristen Scott Thomas) and Kostya

(Mackenzie Crook), dir. Ian Rickson, Royal Court 2009

Final points:

In space of 1896-1902, Chekhov wrote four masterpieces: The Seagull, Uncle Vanya, Three Sisters,

The Cherry Orchard

What is ‘Chekhovian’? It might be the word we use to describe the qualities that are found in this play and in no other on the module. ‘Ibsenism’, for example, might stand for a set of ideas;

‘Chekhovian’ speaks of something less tangible.

Chekhov’s credo: ‘The people I fear are those who seek to read tendencies into what one writes, and who want to see me as straightforwardly liberal or conservative. I am not a liberal – not a conservative – not a gradualist – not an ascetic – not an indifferentist. I should like to be a free artist, and nothing else […] I hate lies and violence in all their forms […] Signs and labels I account mere prejudice. My holy of holies is the human body, health, intelligence, talent, inspiration, freedom, love, and the most absolute freedom, freedom from force and lies, in whatever form these last two might be expressed. This is the programme to which I should adhere were I a major artist.’

Mikhail Vrubel

Six-winged Seraph

(1904)

Isaac Levitan

On Lake (1883)

Isaac Levitan

The Lake (1899-1900)