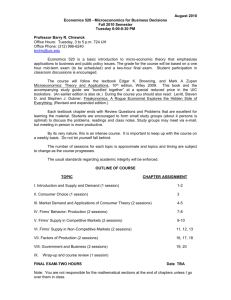

Economics Microeconomics [INTERMEDIATE 2;

advertisement