1. I R :

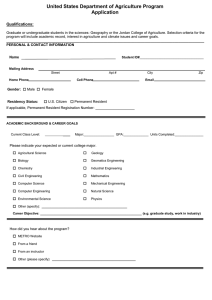

advertisement