Phylum Annelida Class Oligochaeta

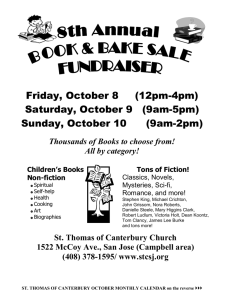

advertisement