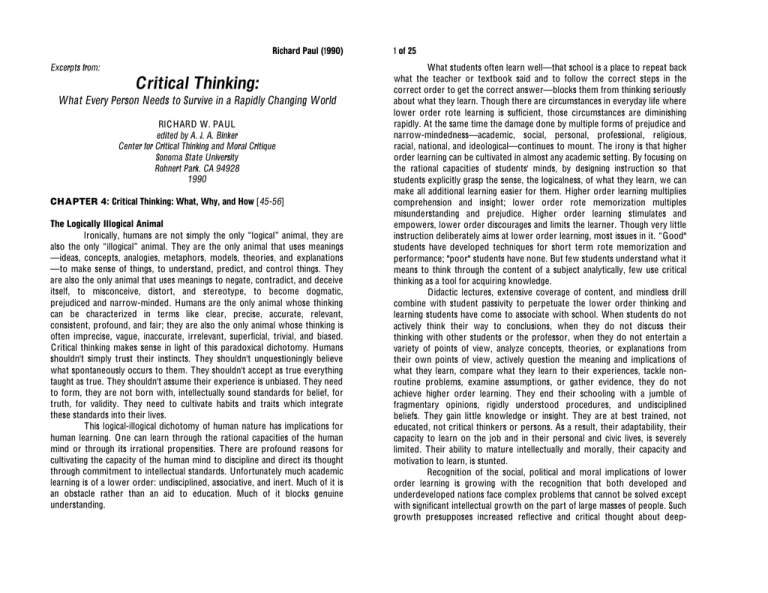

Richard Paul (1990) 1 of 25 Excerpts from:

advertisement