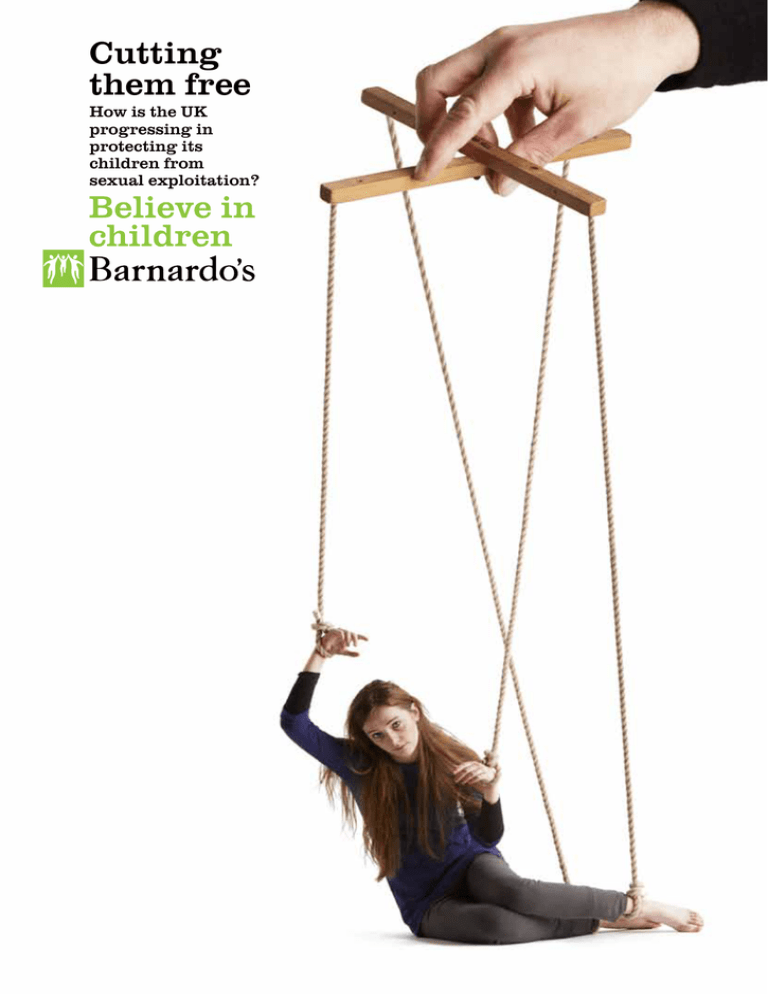

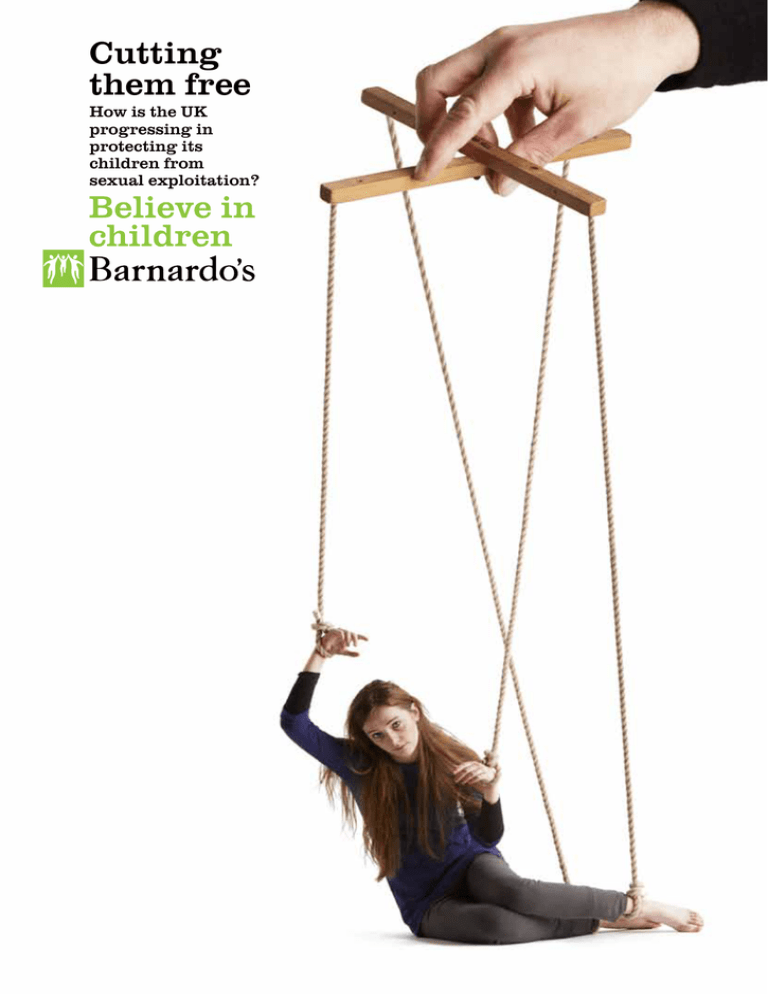

Cutting

them free

How is the UK

progressing in

protecting its

children from

sexual exploitation?

Foreword

My first act on

becoming Chief

Executive of

Barnardo’s in

January 2011

was to launch

the Cut them free

campaign to call

for urgent action

for child sexual

exploitation to be

tackled in the UK. Although Barnardo’s

had been supporting victims of this

horrific abuse for 17 years, there was

still a shocking lack of awareness,

leading to exploitation being overlooked

or the needs of its incredibly vulnerable

victims being sidelined.

Sadly we know that sexual exploitation

can exist in every community, in every

part of the country. So much more must

be done across the UK to identify and

cut free all those children being abused

in this way, and to help those vulnerable

young people who have been preyed upon

to rebuild their lives.

The stories of survival I am told by

young people being supported by

Barnardo’s to escape sexual exploitation

are distressing, but it is even more

heartbreaking to hear how much harder

their recovery is when they are let down

by the agencies which are supposed to

protect them. We need to make sure that

all those who work with children, local

authorities and national governments

recognise sexual exploitation as a form of

child abuse.

2

A survivor of child sexual

exploitation, who was supported

by Barnardo’s, asked at a recent

event: ‘why can’t the authorities spot

vulnerable children before abusers

do’? Professionals, parents, carers

and young people themselves must

have a better understanding of

how to spot the ‘tell-tale signs’ of

exploitation – and what to do if they

suspect a child is being abused.

Our Cut them free campaign has called

for each of the four nations in the UK to

improve their action on tackling child

sexual exploitation. In England this

has meant asking people to support us

in calling for local authorities to make

public commitments to tackling sexual

exploitation. And we have already seen

some real successes – including the

naming of a UK minister with lead

responsibility for sexual exploitation,

and a national action plan for England.

But we will not rest while there are still

children suffering this horrific abuse

who are being ignored. This report sets

out where there has been progress, and

highlights how much still needs to be

done if we are to cut young people in the

UK free from sexual exploitation.

Anne Marie Carrie

Chief Executive, Barnardo’s

Introduction

Barnardo’s has been tackling sexual

exploitation since 1994 when we opened

our first service. Our direct support

of victims now extends through 21

services across the UK. Each year we

work with over 1,000 children and

young people who have been sexually

exploited or are at serious risk of

exploitation, and the numbers keep

rising. In 2010-11 we worked with

1,190 young people affected by sexual

exploitation – an eight per cent rise on

the previous year. And at the time of the

survey, our numbers of service users for

April to September 2011 had increased

by 10 per cent over the same period

in 2010, despite some funding cuts to

our services. We also work to prevent

exploitation by raising awareness of

the issue among young people, parents

and carers, professionals and frontline

staff. In 2010-11, we engaged over 6,600

young people and children in awareness

raising sessions, and produced Spot the

signs leaflets to highlight key signs of

risk to young people, parents/carers

and professionals.

exploitation as a pervasive form of

abuse from which all children are at risk.’1

At the start of 2011, we launched our

Cut them free campaign to call on the

Government and local authorities

to take action to protect vulnerable

young people and children. Our calls

for action were published in Puppet on

a string. The year since has seen much

greater policy and public attention

to sexual exploitation. This report

sets out the progress and, drawing

on a survey of our services across the

UK, focuses on what is still needed if

young people are to be better protected

and supported. Progress in Northern

Ireland, Scotland and Wales is outlined

and the report considers in further

detail how far our campaign calls have

been met in England, following on from

Puppet on a string.

Barnardo’s has been influencing policy

and practice on sexual exploitation

from the start. From the mid-1990s,

we successfully challenged the idea

that exploited children were criminals

involved in prostitution. In the early

2000s, we lobbied for new protections

for under-18s and offences relating to

grooming, coercion and control were

introduced in the Sexual Offences Act

2003. More recently, we influenced

the UK and Welsh Government’s

guidance on safeguarding children

from exploitation. By the end of the

decade, attitudes to young victims had

improved, there was good guidance

on protecting young people and

greater provisions for prosecuting

abusers – but we were still waiting for

‘the major step change in policy and

practice… needed to recognise sexual

1 Barnardo’s (2011) Puppet on a string: The urgent need to cut children free from sexual exploitation.

Barnardo’s, Barkingside.

3

What we know about child

sexual exploitation

Child sexual exploitation is always

abusive. It involves children and young

people being forced or manipulated

into sexual activity. The exploitation

involves sexual activity in exchange

for something, whether money, gifts or

accommodation or less tangible goods

like affection or status. It victimises

children and young people under 18 –

sadly, this abuse is often misunderstood

and viewed as consensual. Yet no child

can consent to their own abuse, even if

they are 16 or 17 years old. We know the

abuse is based on an imbalance of power

which severely limits victims’ options.

The UK Government’s definition

of child sexual exploitation

Sexual exploitation of children and

young people under 18 involves

exploitative situations, contexts and

relationships where young people

(or a third person or persons) receive

‘something’ (e.g. food, accommodation,

drugs, alcohol, cigarettes, affection,

gifts, money) as a result of them

performing, and/or another or others

performing on them, sexual activities.

Child sexual exploitation can occur

through the use of technology without

the child’s immediate recognition;

for example, being persuaded to post

sexual images on the internet/mobile

phones without immediate payment or

gain. In all cases, those exploiting the

child/young person have power over

them by virtue of their age, gender,

intellect, physical strength and/or

economic or other resources. Violence,

coercion and intimidation are

common, involvement in exploitative

relationships being characterised in

the main by the child or young person’s

limited availability of choice resulting

from their social/economic and/or

emotional vulnerability.

The definition of child sexual exploitation

in the green box2 is taken from the

UK Government’s guidance on child

sexual exploitation for England3 and

the national action plan, and is based

on the definition agreed by the National

Working Group of organisations tackling

child sexual exploitation.

Sexual exploitation remains largely

hidden, but there is growing evidence

it is widespread. Our services alone

worked directly with 1,190 young

people in 2010-11. In 2009-10, a UK-wide

survey by the National Working Group

estimated there were over 3,000 service

users across the UK; a third of whom

were Barnardo’s service users. The Child

Exploitation and Online Protection

Centre’s (CEOP) thematic assessment

received 2,000 reports of victims,

despite only limited returns from local

authorities and police forces.

These figures are just the known

cases – we are aware that the number

of undetected victims is likely to be

much higher. In Northern Ireland,

Barnardo’s comprehensive 2011 study

estimated that one in seven young

people are at risk of exploitation. In

Wales, Barnardo’s has estimated that

nine per cent of vulnerable children are

at significant risk of sexual exploitation.

There is currently no estimate of the

prevalence of child sexual exploitation

in Scotland – something we are lobbying

the Scottish Government to address.

Sexual exploitation occurs throughout

the UK, in both rural and urban areas,

to boys and young men as well as girls

and young women. Overall, 10 per cent

of our sexual exploitation service users

are male, but a cluster of services have

developed local prominence for working

with boys and young men, and in those

services around a third of service users

are male. Our frontline experience

2 Definitions of child sexual exploitation used by the UK Government vary but this definition includes the

key characteristics.

3 Department for Children, Schools and Families (2009) Safeguarding children and young people from sexual

exploitation. DCSF, London.

4

and research both show that sexual

exploitation can affect young people

and children from all backgrounds –

however, there are some factors that may

make children and young people more

vulnerable. In particular young people

who go missing frequently and those

who live in care are over-represented

among sexual exploitation victims. Our

2010-11 survey of our sexual exploitation

services found that 44 per cent of all

our service users have gone missing4 on

more than one occasion, and 14 per cent

have been in care.

These findings are mirrored by the

University of Bedfordshire’s study,

which found that over half of all young

people using child sexual exploitation

services on one day in 2011 were known

to have gone missing (a quarter over

10 times), and 22 per cent were in

care.5 There are also strong indications

in this study and others that young

people involved in offending6 and those

excluded from school are also more

vulnerable to exploitation.7

Our work has identified key indications

of vulnerability which may show that

young people are being exploited or are

at significant risk. Our Spot the signs

leaflets list these ‘tell-tale signs’ for

young people themselves to be aware of

and for parents/carers and professionals

to look out for. These key indications of

vulnerability include:

n

going missing for periods of time or regularly returning home late

n regularly missing school or not taking part in education

n appearing with unexplained gifts or new possessions

n associating with other young people involved in exploitation

n having older boyfriends or girlfriends

n suffering from sexually transmitted infections

n mood swings or changes in emotional wellbeing

n drug and alcohol misuse

n displaying inappropriate sexualised behaviour.

4 ‘Missing’ refers to occasions when a child or young person’s whereabouts are unknown, for hours or days; ‘missing’

does not include a child or young person staying out for a short time after they should be at home.

5 Jago, S et al (2011) What’s going on to safeguard children and young people from sexual exploitation? How local

partnerships respond to child sexual exploitation. University of Bedfordshire, Bedford.

6 UCL (2010) Briefing document: CSE and Youth Offending. Jill Dando Institute of Security and Crime Science,

UCL, London.

7 Jago, S et al (2011) What’s going on to safeguard children and young people from sexual exploitation? How local

partnerships respond to child sexual exploitation. University of Bedfordshire, Bedford.

5

A changing picture: emerging

trends noted by Barnardo’s services

Barnardo’s annual survey of its 21 child

sexual exploitation services tracks local

variation and emerging trends. It enables

us to assess how child sexual exploitation

is changing and informs our practice,

research and policy.

Models of exploitation

There is no single form of child sexual

exploitation. Young women and girls

are being exploited by older men who

appear to be their boyfriend, but this is

only one model of sexual exploitation.

Older ‘girlfriends’, peers (some of whom

have been abused), loose networks of

abusers, more organised groups and

some criminal gangs have been identified

as perpetrators. Our 21 services find

that sexual exploitation varies between

areas and its form can change quickly.

As in previous years, the 2010-11 survey

reiterated this diversity.

Most services noted significant change

in the local form of sexual exploitation –

but not in the same direction. Eight

said that peer-based exploitation was

becoming more common, while two

said that they were seeing more abuse

by ‘older boyfriends’ again, after a

rise in peer-based or opportunistic

exploitation. Barnardo’s has found

that child sexual exploitation is much

more likely to happen in private

than in public, and this year’s survey

showed that street-based grooming and

exploitation remains rare. But services

reported increased exploitation in semipublic areas such as parks and cafes.

Echoing this, three services highlighted

the role of parties in putting groups

of young people at significant risk

of exploitation. Whether hosted by

older young people or risky adults,

these events are perceived as ‘safe’ by

young people as they feel protected

by being in a group. As one manager

said: ‘Friendship groups or pairs

6

[are] going to known risky people’s

houses feeling this will make them

safer, but [it is] putting more young

people at risk’. Services stress the

need for greater preventative work

to raise young people’s awareness

of sexual exploitation, judgement of

risk and knowledge of how to keep

safe. In particular, young people need

to be aware that ready availability of

alcohol and drugs may increase their

vulnerability to abuse.

Organised exploitation and internal trafficking

The extent of organised exploitation

has become increasingly apparent to

our services in the last three years.

Organised sexual exploitation is the

most sophisticated form of this abuse,

based on links between abusers, and

often involves victims being moved to

other cities or towns for exploitation

(referred to as ‘internal trafficking’).

The 2010-11 survey showed that

services continue to be concerned

about the extent of networked and

organised exploitation: the same

adults linked to victims who do not

know each other; abusers fostering

links between vulnerable children or

young people; and victims themselves

being forced to engage vulnerable

peers, for example through links made

in secure accommodation.

Services are seeing the movement of

young people for sex within their region

and across the UK. In some cases,

businesses are being used as hubs for the

organisation of this exploitation.

Overall, the survey showed that one in

six of our service users are known to

have been moved for exploitation within

the UK, but in some services many

more service users have been moved.

Four services reported that a quarter of

service users had been moved, and for

another three services this rises to half

of all service users.

Involvement of peers in exploitation

Eight services reported an increase in

exploitation by peers – either directly

as abusers or indirectly by linking

victims with abusers. It can be difficult

to distinguish between young people’s

involvement in direct and indirect

peer exploitation, and some young

people may be involved in both. Direct

peer exploitation refers to young

people who actively exploit their peers

themselves. Indirect peer exploitation

refers to young people engaging

their peers in exploitation, but not

initiating the abuse. Often these young

people are victims of exploitation, or

fear abuse, and are drawing others

in as protection. Sometimes they are

pressured into bringing others to be

abused. Indirect exploitation typically

involves young people of similar ages,

but some services reported that young

teenagers are increasingly used to

engage older teenagers in exploitation,

making the initial contact so potential

victims feel safer than they might if

approached by an adult.

Exploitation of younger children

Services are still seeing young children

drawn into this form of abuse. Five

services raised it as a major concern,

identifying children as young as 11 at

high risk of sexual exploitation, although

the majority were working with children

from 13 years old.

The role of technology in exploitation

Exploited young people and children are

typically abused in person, but sexual

exploitation also takes place over the

internet, through mobile phones, online

gaming and instant messaging. This

is not surprising given how central

technology is now to young people’s

lives, and the issue has long been a major

concern for our services. However, the

services reported that the scale of online

and mobile abuse has markedly increased

even since 2010. Almost all services

reported it as an increasing priority, and

some have identified that the majority

of their service users were initially

groomed via social networking sites and

mobile technology.

‘The use of technology is such a big

issue. I hear of young people who post

inappropriate pictures of themselves on

the internet through the encouragement

of others. I hear about grooming of

young people by older adults over the

internet which progresses onto mobiles.

Sexual bullying and threats over the

internet and mobiles, we hear about this

all the time.’ [Service manager]

Young people, parents/carers and

professionals need to be more aware

of how such technology can be used by

abusers. Our services help young people

to understand what could be risky in

the many associations, conversations

and images they are surrounded by

when using this technology. In addition,

Barnardo’s lobbied for an amendment8

to the current Education Bill, to include

guidance to schools not to automatically

delete explicit images from mobile

phones. Images may constitute

evidence of abuse for any subsequent

prosecution, and could also raise

safeguarding concerns.

Prosecutions

Although legislation has created

offences around child sexual

exploitation,9 there have been very few

prosecutions so far. In 2010, only 57

people (over 21 years old) were found

guilty of offences relating to sexual

exploitation in England and Wales – and

these include those found guilty for

offences relating to trafficking adults.10

8 Our call for the guidance was raised by Lady Benjamin and acknowledged by Lord Hill.

9 England and Wales: Sexual Offences Act 2003. Northern Ireland: Sexual Offences (Northern Ireland) Order 2008.

Scotland: Protection of Children and Prevention of Sexual Offences (Scotland) Act 2005.

10Ministry of Justice (2011) Criminal Statistics England and Wales, 2010 (Table S5.7). MoJ, London.

7

The official statistics show a very small

increase on 2009, when the total was

55. However, convictions for abuse

of children through prostitution and

pornography have risen more markedly

over the last year, from 32 to 47.

Our services also indicate that there

has been some slight increase in the

prosecution rate – with offenders often

tried for other offences such as rape or

sexual activity with a child under 13 or

under 16. Across the UK, our services

knew of 137 police investigations

involving their service users as victims

of crimes relating to sexual exploitation.

Of these, seven are ongoing and 40 have

been taken to prosecution – mostly for

grooming via the internet (12 cases),

abuse of children through prostitution

(six cases), sex with a child under

13 (six cases) and rape (five cases).

Of the 37 prosecutions which have

concluded, two-thirds (24) have resulted

in conviction – eight for internet

grooming, five for abuse through

prostitution and three for rape.

It is concerning that the conviction

rate is still lower than it should be,

depressed by only partial understanding

of child sexual exploitation within

the criminal justice system which can

result in misunderstandings of the

relationship between victim and offender

and insufficient attention to the needs

of the young victim in giving evidence.

Prosecutions can be traumatic for young

victims, and Barnardo’s knows that

the invasive nature of the court cases

can stop young people from reporting

the horrific abuse or from providing

evidence. Until young victims are better

supported through this daunting and

potentially damaging process, for

example by making better use of the

available special measures for court,

there will only be marginal increases in

the number of prosecutions.

As well as seeking prosecutions,

police can try to disrupt exploitation –

for example by issuing abduction

notices, which state that the offender

must not be in the company of the

young person. Disruption tactics

are becoming more widely used by

police – either in place of or alongside

efforts to prosecute. Our services

were aware of at least 16 notices11

issued to abusers, but also said that

much more could be done to disrupt

and deter abuse by using such tactics

more widely.

11 Six abduction notices, five harbouring notices and five sex offender prevention orders.

8

National and local progress

on sexual exploitation

2011: A busy year

When Barnardo’s launched its Cut them

free campaign at the start of 2011, we

welcomed the greater interest that was

being shown in identifying and tackling

child sexual exploitation, but said that

we were still waiting for ‘the major step

change in policy and practice… needed

to recognise sexual exploitation as a

pervasive form of abuse from which all

children are at risk.’12

From the start, 2011 did see far greater

policy and public attention to sexual

exploitation – this report will consider

whether it has amounted to the major

step change required.

January:

Cut them free

campaign

launched.

May: Tim Loughton

announces national

action plan to be

published in autumn.

February: Children’s

Minister Tim Loughton

appointed ministerial lead

on child sexual exploitation.

June: CEOP’s

thematic

assessment is

published.13

October: University of

Bedfordshire publishes study of

local action in England.

October: Launch of Office of the

Children’s Commissioner (England)

two-year inquiry into child sexual

exploitation by gangs and groups.

November: Barnardo’s study within

Northern Ireland14 is published.

November: Tackling Child Sexual

Exploitation, the Government’s national

action plan for England is launched at

Barnardo’s event.

Progress across the UK Nations

So by late 2011 there had been some

marked progress on sexual exploitation,

specifically on the evidence base,

governmental recognition of the problem

and provisions for action. Much of this

had already been achieved in Wales, so

the greatest progress in 2011 was made

in England, but Barnardo’s campaigns

in Scotland and Northern Ireland also

catalysed change.

12Barnardo’s (2011) Puppet on a string: The urgent need to cut children free from sexual exploitation.

Barnardo’s, London.

13 CEOP (2011) Out of Sight, Out of Mind: Breaking down the barriers to understanding child sexual exploitation.

CEOP, London.

14Barnardo’s (2011) Not a world away. The sexual exploitation of children and young people in Northern Ireland.

Barnardo’s Northern Ireland, Belfast.

9

Barnardo’s Northern Ireland published a report exposing the extent

of child sexual exploitation in Northern Ireland (NI). Not a world

away found that sexual exploitation is an issue of concern for almost

two-thirds of girls in residential care homes in NI who were included

in the study.

It also found that sexual exploitation affects both males and females

and that, in half of the cases identified, the abuse lasted at least one

year and in over 16 per cent, it lasted three or more years.

In light of these findings, Barnardo’s Northern Ireland is calling

for the NI Policing Board to incorporate child protection including

sexual exploitation as a priority in the forthcoming Policing Plans

and for the Health and Social Care Board to draw together an

action plan to tackle sexual exploitation head on. Supporters are

being asked to sign up to a petition to the NI Policing Board to

urge them to make child sexual exploitation a priority at

www.barnardos.org.uk/cutthemfree

Barnardo’s Cymru welcomed the review of the

implementation of new Child Sexual Exploitation

Safeguarding Guidance (2011) being undertaken by

the Welsh Government – this is an important step in

addressing the gap between policy and practice in

relation to child sexual exploitation safeguarding

in Wales. The Welsh Government commissioned

Barnardo’s Cymru to deliver implementation

support events across Wales in early 2011 and all

Local Safeguarding Children’s Boards (LSCBs)

attended. Examples of good practice are available

and we hope that new collaboration arrangements

being put forward by the Welsh Government will

support the growth of good practice across Wales.

Our Seraf service is doing innovative work to assist

local authorities in their workforce development in

relation to child sexual exploitation by the sharing

of skills, knowledge and expertise through our new

Practitioner Mentoring Programs.

Unfortunately a high proportion of the children and young people who are

identified as needing support still have those needs unmet in Wales. There is a

continued need for better multi-agency responses to children and young people

who go missing so that risk of sexual exploitation can be identified earlier

and children and young people can be better safeguarded from this abuse.

Barnardo’s Cymru Seraf Service is working with the police and a number of

local authorities to support the development of better responses to children and

young people who go missing. Briefings on internal trafficking and child sexual

exploitation are being delivered to three police forces across Wales.

10

Barnardo’s Scotland has been calling for the Vulnerable children and young

people: sexual exploitation through prostitution guidelines (2003) to be updated

along the lines of recent developments in Wales and England, and for action

to be taken on the recommendation in the existing guidelines that research be

carried out into the nature and scope of child sexual exploitation in Scotland.

These guidelines should be revised and refreshed to take account of recent

legal changes, and also to assess the role of the internet and text messages in

child sexual exploitation which our services have identified as having changed

significantly in recent years.

Barnardo’s recently submitted a petition to the Scottish Parliament, which

was signed by over 3,000 people. The petition calls on the Scottish

Government to:

n carry out research on the nature of sexual exploitation in Scotland

n tell us what their progress is in tackling this issue

n develop robust new policies to tackle sexual exploitation.

There is still the need to continue to push for this

progress in Scotland in 2012.

In England, Barnardo’s called for a national action

plan to tackle child sexual exploitation and a lead

government minister, and both have been met with

the appointment of the Children’s Minister as lead

on child sexual exploitation and the launch of the

national action plan. In addition, Barnardo’s has

issued a direct call to local authorities to publicly

commit to addressing child sexual exploitation; this

commitment is made by pledging to develop a local

action plan and assess their progress in protecting

young people from child sexual exploitation against

the following key points:

n What

system is in place to monitor the number of

young people at risk of sexual exploitation?

n Does the Local Safeguarding Children’s

Board have a strategy in place to tackle child

sexual exploitation?

n Is there a lead person with responsibility for

coordinating a multi-agency response?

n Are young people able to access specialist support

for children at risk of sexual exploitation?

n How are professionals in the area trained to spot the signs of child sexual exploitation?

See the local authority checklist for more detail at www.barnardos.org.uk/

cutthemfree_labriefing.pdf

Throughout 2012, Barnardo’s will be continuing to urge local authorities to take

action to tackle this form of abuse.

11

Having a ministerial lead and a

national action plan for child sexual

exploitation were key policy calls in our

Cut them free campaign for England.

We called for a lead minister ‘to provide

dedicated attention to this issue’. The

appointment of the minister has given

greater prominence to child sexual

exploitation as a national responsibility

in England, and we welcome the

attention that the minister has given it

so far. Barnardo’s will scrutinise this to

see whether it is maintained.

We called for a national action plan

‘to embed guidance and overcome

the barriers to more effective local

delivery’. The publication of the national

action plan has set out in broad terms

how the responsibility is to be shared

across central government and by

local authorities, police forces and

other agencies. Barnardo’s welcomes

the plan, especially its emphasis on

cross-departmental working to tackle

sexual exploitation, its proposals

to raise awareness of child sexual

exploitation and improve training for

some professionals, and recognition of

the need to improve the prosecution rate

and experience for victims. However,

much in the plan is ongoing rather than

new, and relatively few of the new actions

commit government departments or

statutory agencies to specific changes.

This means that further progress is

largely dependent on goodwill, which is a

concern during these challenging times.

How far the national action plan

met our calls is set out against our

four recommendations.

1. Raise awareness to improve early

identification of child sexual exploitation.

National action plan commitments:

n Barnardo’s calls were heard with

specific commitments to awareness

raising among professionals, young

12

people and parents and training for

some frontline staff.

Work to do:

Barnardo’s will monitor how these

commitments and intentions are

implemented. In particular, we

will scrutinise the Department

for Education’s assessment of

how it could help LSCBs raise

awareness and understanding of

child sexual exploitation.

n

2. Improve statutory responses and the

provision of services. National action

plan commitments:

n Barnardo’s calls have been recognised

in the emphasis on improving

responses to this abuse but there

is limited mention of the need for

additional specialist services.

Work to do:

n Barnardo’s will assess how the

Department for Education is helping

LSCBs to track and respond to sexual

exploitation, especially whether it

is encouraging LSCBs to establish

a child sexual exploitation working

group or appoint a lead officer to co-ordinate action.

n Barnardo’s will respond to the Home

Office’s proposals for increased

funding of rape/sexual abuse

support services, emphasising the

need to ensure this funding will also

provide specifically for victims of

sexual exploitation.

3. Improve the evidence.

National action plan commitments:

n Barnardo’s calls are partly recognised

in the acknowledgement that ‘areas

cannot conclude [child sexual

exploitation] is not an issue for them

in the absence of a proper assessment’

(p10), and the intention to support

LSCBs in mapping levels. However,

there is no provision for a national

reporting mechanism or standardised

process by which services can share

concerns with police.

Work to do:

n Barnardo’s welcomes the recognition

of a need to map child sexual

exploitation levels and to monitor

ongoing prevalence, using information

from all relevant agencies. However,

we are disappointed at the absence of a

national reporting mechanism.

n Barnardo’s will encourage the

Department for Education and the

Home Office to consider how systems

can be established for information

sharing between services and the

police, as part of the work to improve

responses to sexual exploitation. We

will also assess whether adequate

resources are given to making this

local data into a national picture.

4. Improve prosecution procedures.

National action plan commitments:

n Barnardo’s calls are acknowledged

in the emphasis on young witnesses’

welfare as a priority throughout

prosecutions, and on improving police

and justice agencies’ effectiveness in

prosecutions. However, there are few

new commitments.

Work to do:

n Barnardo’s will ask the Ministry of

Justice to show how their intentions to

improve support for young witnesses

and responses to intimidation have

been implemented.

n We will monitor whether pre-trial

video-recorded cross-examination

is used, and will ask the Ministry of

Justice to explain its decision if the

provisions are not used.

n We will respond to the consultation for

the review of victims’ services.

The Department for Education will be

publishing a review of progress on the

national action plan in Spring 2012.

Barnardo’s hopes that this review

will maintain momentum on tackling

child sexual exploitation, but we will

continue to monitor progress against

our campaign calls. Specifically, we will

assess whether the emphasis placed on

local responsibility for tackling child

sexual exploitation has led LSCBs to

improve their responses – or the fact

that the national action plan did not

require action from LSCBs has allowed

momentum to slip.

Local progress on sexual

exploitation

In England, the updated government

guidance on addressing child sexual

exploitation15 sets out how Local

Safeguarding Children Boards and

statutory agencies should act to protect

young people. However, it is evident that

the guidance is only being used in some

areas and not in full. The University of

Bedfordshire’s comprehensive study of

local action over child sexual exploitation

found that only a third of LSCBs were

implementing the guidance. Such

variation in local awareness of the issue

and statutory responses to it is also

clear from Barnardo’s evaluation of our

Recovery Project which delivers intensive

support to victims of exploitation across

London.16 Few of the 25 boroughs which

have received the service so far follow the

pan-London protocol on safeguarding

children and young people from sexual

exploitation, which was jointly developed

by all 33 London boroughs.17

Our services show that this difference

in awareness and approach is mirrored

with LSCBs across England and Wales

(which has comprehensive guidance on

sexual exploitation) and in equivalent

child protection bodies in Scotland and

Northern Ireland. Overall, the services

described their links with LSCBs or their

15 DCSF (2009) Safeguarding children and young people from sexual exploitation. DSCF, London.

16 This Metropolitan Police Service-funded provision runs from 2008-2012.

17 London Safeguarding Children Board (2006) Safeguarding children abused through sexual exploitation.

London Councils, London.

13

equivalents in positive terms – half said

they had ‘very good’ relationships. But

there were clear gaps and some services

indicated concerns that child protection

bodies are downgrading child sexual

exploitation as a priority, even in areas

with an established specialist service

highlighting the issue.

Research from Barnardo’s services

shows what enables young people to be

protected from sexual exploitation and

supported if they have been exploited.

There are five clear lessons from our

longer-term work:

1. Raising awareness among young

people and practitioners is

crucial in preventing exploitation

and identifying victims – early

identification and intervention is

known to significantly reduce the

potential harm of sexual exploitation.

2. A clear multi-agency system to

identify and respond to local cases of

exploitation is essential if victims and

those at risk are to receive timely and

appropriate interventions.

3. Having a lead worker to co-ordinate

the multi-agency response can

make planning and delivering it

more efficient.

4. Gathering and assessing data on

levels and risks of child sexual

exploitation is fundamental to

understanding the profile of

exploitation, and guiding the response.

5. Specialist services are best placed to

provide the necessary support; sexual

health services, child and adolescent

mental health services and other

statutory agencies play a key role but

may not develop a fuller picture of the

young person’s situation.

Barnardo’s Cut them free campaign

includes a direct call to local authorities

in England to publicly commit to

addressing sexual exploitation. This

commitment is made by pledging to

18www.barnardos.org.uk/cutthemfree

14

develop a local action plan, and signing

up to a minimum standard of action

based on these five key elements – drawn

from the lessons above.18 Barnardo’s

five-step checklist provides English local

authorities with a way to assess their

progress in protecting young people

from sexual exploitation:

Checklist for English

local authorities

q What system is in place to monitor

the number of young people at risk

of child sexual exploitation?

q Does your LSCB have a

strategy in place to tackle child

sexual exploitation?

q Is there a lead person with

responsibility for coordinating

multi-agency response?

q Are young people able to access

specialist support for children at

risk of child sexual exploitation?

q How are professionals in your area

trained to spot the signs of child

sexual exploitation?

Barnardo’s has contacted all local

authorities and all councillors setting out

the importance of tackling child sexual

exploitation and asking them to ensure

that their local authority does sign up to

the Cut them free commitment. The public

can also contact their council through our

campaign website to ask them to commit

to taking action. By late December, over

7,000 people had joined the campaign,

showing the strength of public concern

over sexual exploitation. Despite this

considerable public support, and

Barnardo’s contacting councils directly,

only 73 of England’s 152 local authorities

had joined the campaign with a public

commitment to tackle sexual exploitation.

Our campaigning work will continue to

ensure that local authorities throughout

England commit to taking real action.

Recommendations to maintain

momentum and ensure change

Much has been done this year to raise

the profile of child sexual exploitation

as a priority concern for the UK, and

specifically for authorities which have

local responsibility for protecting young

people. However, we are yet to see how

this effort has translated into action, so

Barnardo’s and all agencies focused on

tackling sexual exploitation will need to

ensure that the momentum is maintained

and leads to real change.

In Northern Ireland urgent action is

still needed to protect young people

from this abuse. More effective statutory

responses will be in place if the Northern

Ireland Policing Board incorporates child

protection, including sexual exploitation,

as a priority in the forthcoming

Policing Plans to recognise the critical

importance of this area of work and if

the Health and Social Care Board draws

together an action plan to tackle sexual

exploitation head on.

To tackle the problem more effectively

in Scotland, the Scottish Government

needs to review and update the existing

guidelines, dating from 2003, and

commission research so the nature and

scope of child sexual exploitation in

Scotland can be fully understood. A new

robust set of policies will be required

to tackle sexual exploitation and the

Scottish Government should set out

any progress they make in addressing

this issue.

In Wales local authorities must

address the gap between those

numbers of children and young people

who are identified as needing support

and those who still have those needs

unmet. Police and local authorities

should also continue to work to

improve multi-agency responses for

children and young people who go

missing so that risk of child sexual

exploitation can be identified earlier

and children and young people can be

better safeguarded from abuse through

child sexual exploitation.

In England work must continue to focus

the efforts of local authorities and LSCBs

on tackling this abuse, and it must be

acknowledged that the four key changes

called for in Puppet on a string still need

significant work before they are met.

Raise awareness

The national action plan for England sets

out many ways that awareness is to be

raised – among young people, parents/

carers and professionals. However, there

is some evidence from our services that

agencies have reduced their uptake of

awareness raising and training on child

sexual exploitation over the past year.

Our services delivered school sessions on

child sexual exploitation to 6,814 young

people across the UK (6,676 in England)

but this was a third fewer than in 200910. Acknowledgement and recognition

of child sexual exploitation remains very

patchy – even in areas where Barnardo’s

services are highlighting the problem –

so this trend is worrying.

Barnardo’s welcomes the Government’s

intention to highlight the issue of

exploitation in its review of Personal

Social Health and Economic Education,19

but we hope that other education

providers which are not subject to

the guidance, such as academies, will

also raise awareness of child sexual

exploitation among their pupils. We

urge all local authorities to provide

information and training on sexual

exploitation to both frontline and

strategic professionals responsible

for young people’s welfare. We will be

monitoring the implementation of plans

to improve the training of police officers

and social workers.

Improve support

Young people who are sexually exploited

need timely and tailored interventions if

19 This is also delivered in short-stay schools, formerly known as pupil referral units.

15

they are to be cut free from their abuse.

The national action plan encourages

LSCBs to assess the local need and to

develop a response strategy – but it

does not oblige them to do so. We are

concerned that many will continue

to sideline the issue, especially given

severe budget cuts. Investing in early

identification and specialist support

could reduce overall expenditure

by many agencies. An evaluation by

Barnardo’s and Pro Bono Economics20

has shown that spending on specialist

services potentially saves taxpayers’

money; for every £1 spent on Barnardo’s

child sexual exploitation services, £12

may be saved by the Exchequer over the

longer term.

As a minimum, local authorities

should devise a multi-agency strategy

incorporating police, social services,

health and education and appoint a

lead officer to co-ordinate responses.

Barnardo’s knows that one of the most

successful strategies for addressing

exploitation is to bring specialist support

services to work alongside police

and, where possible, social or health

services. The study by the University of

Bedfordshire illustrates this. Barnardo’s

will continue our campaign, calling

on local authorities to protect young

people from child sexual exploitation,

and we will continue working with the

Association of Chief Police Officers and

the Local Government Association to

inform police and council responses to

this abuse.

Improve the evidence

Recent research has improved our

understanding of how widespread the

problem of child sexual exploitation

is – and has also highlighted that there

is much still to do to raise awareness

of the issue. The English Office of the

Children’s Commissioner’s inquiry into

child sexual exploitation by groups

and gangs will considerably extend the

evidence of these forms of exploitation,

and contribute to the overall picture.

The national action plan also mentions

the importance of developing a fuller

understanding of the levels and forms

of child sexual exploitation, but it is not

clear how this is to be achieved. Child

Exploitation and Online Protection

Centre has ongoing responsibility for

centrally collating local data, and can

call for local authorities to provide their

evidence. However, data analysis would

need to be adequately resourced – we

will wait to see whether the national

picture can be updated.

Improve prosecutions

Prosecutions have been a particular

cause for concern – there are low rates of

successful prosecutions and the process

can be a negative experience for young

victims. Our services indicate that some

police forces are becoming far better in

their engagement with young victims

and are often supportive through the

preparation for trial and the prosecution.

However, cross-examination can still be

very traumatic. Barnardo’s welcomes

the national action plan’s emphasis on

enabling young victims and witnesses

to give their best evidence in court.

However, we are concerned that there

will still be limited understanding of this

complex issue within the courts and the

wider criminal justice system. Barnardo’s

will be monitoring whether the efforts do

indeed improve the prosecution process

and enhance victim support.

20Barnardo’s and Pro Bono Economics (2011) Reducing the risk, cutting the cost: An assessment of the potential savings

from Barnardo’s interventions for young people who have been sexually exploited. Barnardo’s, Barkingside.

16

17

Cutting them free

How is the UK progressing in

protecting its children from

sexual exploitation?

© Barnardo’s, 2012

All rights reserved

No part of this report, including

images, may be reproduced or

stored on an authorised retrieval

system, or transmitted in any

form or by any means, without

prior permission of the publisher.

Some images posed by models.

Cover image:

Photography by Marcus Lyon

www.barnardos.org.uk

Head Office

Tanners Lane

Barkingside, Ilford

Essex IG6 1QG

Tel: 020 8550 8822

Barnardo’s Registered Charity Nos.

216250 and SC037605 14354dos11