Document 13036475

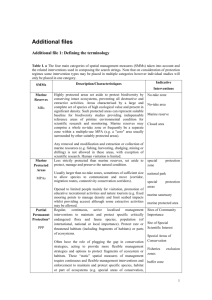

advertisement