Touchstone 2012 Kansas State University No. 44

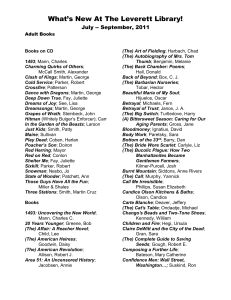

advertisement