Epistemology NQ Support Material Philosophy Higher

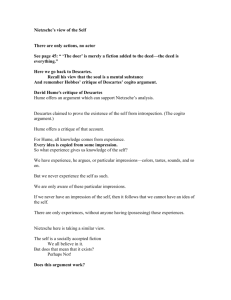

advertisement