BREEDING GROUND AFFILIATION AND MOVEMENTS OF GREATER

advertisement

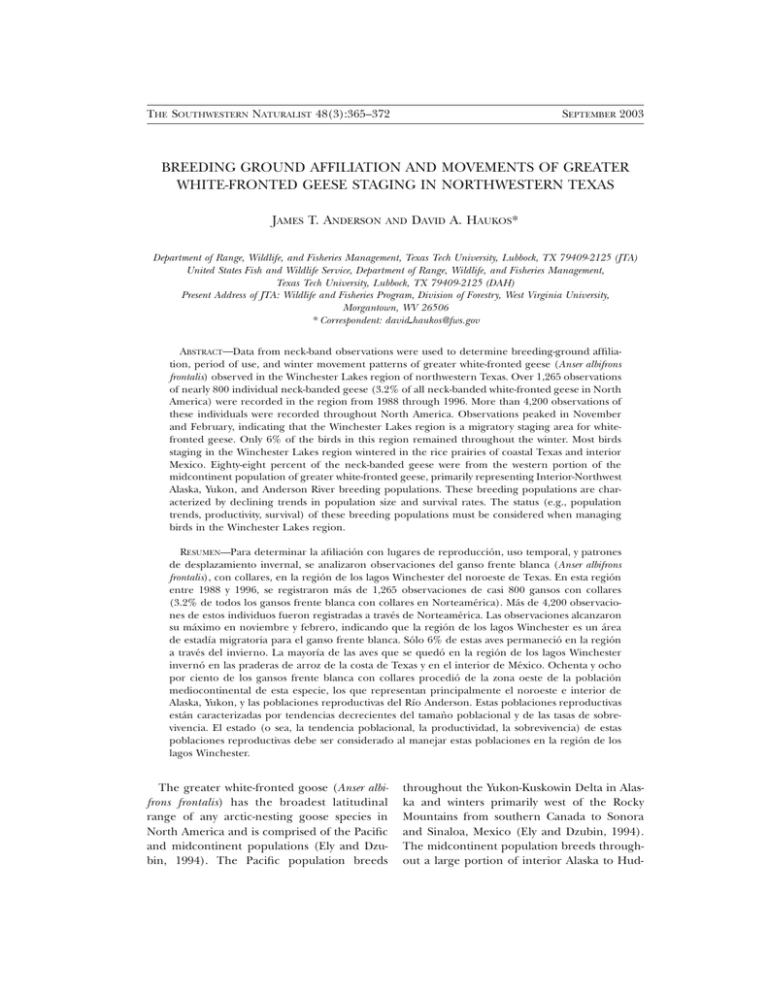

THE SOUTHWESTERN NATURALIST 48(3):365–372 SEPTEMBER 2003 BREEDING GROUND AFFILIATION AND MOVEMENTS OF GREATER WHITE-FRONTED GEESE STAGING IN NORTHWESTERN TEXAS JAMES T. ANDERSON AND DAVID A. HAUKOS* Department of Range, Wildlife, and Fisheries Management, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409-2125 (JTA) United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of Range, Wildlife, and Fisheries Management, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, TX 79409-2125 (DAH) Present Address of JTA: Wildlife and Fisheries Program, Division of Forestry, West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV 26506 * Correspondent: davidphaukos@fws.gov ABSTRACT Data from neck-band observations were used to determine breeding-ground affiliation, period of use, and winter movement patterns of greater white-fronted geese (Anser albifrons frontalis) observed in the Winchester Lakes region of northwestern Texas. Over 1,265 observations of nearly 800 individual neck-banded geese (3.2% of all neck-banded white-fronted geese in North America) were recorded in the region from 1988 through 1996. More than 4,200 observations of these individuals were recorded throughout North America. Observations peaked in November and February, indicating that the Winchester Lakes region is a migratory staging area for whitefronted geese. Only 6% of the birds in this region remained throughout the winter. Most birds staging in the Winchester Lakes region wintered in the rice prairies of coastal Texas and interior Mexico. Eighty-eight percent of the neck-banded geese were from the western portion of the midcontinent population of greater white-fronted geese, primarily representing Interior-Northwest Alaska, Yukon, and Anderson River breeding populations. These breeding populations are characterized by declining trends in population size and survival rates. The status (e.g., population trends, productivity, survival) of these breeding populations must be considered when managing birds in the Winchester Lakes region. RESUMEN Para determinar la afiliación con lugares de reproducción, uso temporal, y patrones de desplazamiento invernal, se analizaron observaciones del ganso frente blanca (Anser albifrons frontalis), con collares, en la región de los lagos Winchester del noroeste de Texas. En esta región entre 1988 y 1996, se registraron más de 1,265 observaciones de casi 800 gansos con collares (3.2% de todos los gansos frente blanca con collares en Norteamérica). Más de 4,200 observaciones de estos individuos fueron registradas a través de Norteamérica. Las observaciones alcanzaron su máximo en noviembre y febrero, indicando que la región de los lagos Winchester es un área de estadı́a migratoria para el ganso frente blanca. Sólo 6% de estas aves permaneció en la región a través del invierno. La mayorı́a de las aves que se quedó en la región de los lagos Winchester invernó en las praderas de arroz de la costa de Texas y en el interior de México. Ochenta y ocho por ciento de los gansos frente blanca con collares procedió de la zona oeste de la población mediocontinental de esta especie, los que representan principalmente el noroeste e interior de Alaska, Yukon, y las poblaciones reproductivas del Rı́o Anderson. Estas poblaciones reproductivas están caracterizadas por tendencias decrecientes del tamaño poblacional y de las tasas de sobrevivencia. El estado (o sea, la tendencia poblacional, la productividad, la sobrevivencia) de estas poblaciones reproductivas debe ser considerado al manejar estas poblaciones en la región de los lagos Winchester. The greater white-fronted goose (Anser albifrons frontalis) has the broadest latitudinal range of any arctic-nesting goose species in North America and is comprised of the Pacific and midcontinent populations (Ely and Dzubin, 1994). The Pacific population breeds throughout the Yukon-Kuskowin Delta in Alaska and winters primarily west of the Rocky Mountains from southern Canada to Sonora and Sinaloa, Mexico (Ely and Dzubin, 1994). The midcontinent population breeds throughout a large portion of interior Alaska to Hud- 366 The Southwestern Naturalist son Bay, Canada (Bellrose, 1980; King and Derksen, 1986; Sullivan, 1998; Haukos, 2001). During winter, portions of the midcontinent population are most abundant in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley in eastern Arkansas, coastal Louisiana and Texas, and the Mexican states of Tamaulipas and Vera Cruz (Ely and Dzubin, 1994). They might winter farther north during mild winters in lower Midwestern and Great Plains states (Ely and Dzubin, 1994). The midcontinent population has maintained a relatively stable population from 1992 through 2000, with an average count of 845,514 (range 5 622,200 to 1,129,378) based on the cooperative fall survey conducted in Saskatchewan, which is the official monitoring survey of greater white-fronted geese (Sullivan, 1998; Haukos, 2001). In contrast to the midcontinent population, white-fronted geese in Interior-Northwest Alaska (about 10% of the overall midcontinent population) have exhibited declining trends since 1983 (Spindler et al., 1999), and Interior Alaska birds have exhibited lower survival rates compared to other populations (Ely and Schmutz, 1999). Migration staging and wintering locations for a large portion of the midcontinent population of white-fronted geese are unfortunately unknown (Ely and Dzubin, 1994). The Winchester Lakes wetlands complex in the Rolling Plains of northwestern Texas has recently (ca. 1990) begun to be used by white-fronted geese (Haukos, 2001). The number of white-fronted geese using the Winchester Lakes region varies annually, but totaled greater than 100,000 birds during a survey in early February 1995 ( J. Winship and J. Haskins, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, pers. comm.). However, not more than 10,000 white-fronted geese have been recorded during the annual cooperative midwinter waterfowl inventory in early January ( J. Ray, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, pers. comm.; Haukos, 2001). Despite potentially large numbers of white-fronted geese in this region, little is known about the breedingground affiliations, movements, and period of use by this population in the Winchester Lakes region. Such information would aid in setting regional harvest regulations and understanding potential impacts of events occurring during migration and wintering periods on recognized breeding populations of greater whitefronted geese. vol. 48, no. 3 METHODS The Winchester Lakes region (33809 to 338509N, 9983 to 998569W) of northwestern Texas was the focal area of the study. This area is located in the Rolling Plains of Texas and encompasses portions of Knox, Baylor, Haskell, and Throckmorton counties. The region is characterized by native grassland, with scattered mesquite (Prosopis glandulosa) and juniper (Juniperus), with cropland, principally winter wheat, interspersed; the primary landuse is cattle production. Wetlands used by white-fronted geese in the region are comprised of approximately 10 named depressional wetlands (e.g., Winchester Lake, Thompson Lake, Zahn Lake), nearly 50 small (,3 ha) livestock tanks, and 3 larger (25 to 100 ha) impoundments (Benjamin, Davis, Catharine lakes). Wetland availability varies considerably in response to precipitation, with only the larger impoundments containing reliable water through extended drought. Most of the wetlands are characterized by open water with a narrow ring of emergent vegetation (e.g., Typha and Scirpus). Larger impoundments are surrounded by woody vegetation (e.g., mesquite, juniper, and salt cedar [Tamarix]). All wetlands are on or surrounded by private land. Neck-Band Data As part of a continental neckbanding project, 24,548 greater white-fronted geese from throughout their breeding range were captured and fitted with individually-coded neck bands from 1988 to 1996. Personnel from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Texas Tech University, and Texas Parks and Wildlife Department observed and recorded neck-banded geese between 1991 and 1998 in the Winchester Lakes region. Other participants in the project recorded neck bands throughout Canada, United States, and Mexico. We obtained all continental neck-band observations for white-fronted geese that were seen at least once in the Winchester Lakes region between 1991 and 1998 from the neck-band database maintained by the Canadian Wildlife Service. The first observation of a neck-banded white-fronted goose in the region occurred on 16 March 1991 and the final observation was on 15 February 1998. The earliest calendar date a bird was observed was 28 October 1995 with the latest 16 March 1991. Most observations of neck-banded geese in the region were recorded during 1995 (33% of 1,265 total observations) and 1996 (56% of observations), when a Texas Parks and Wildlife Department biologist and personnel from Texas Tech University surveyed the area daily from November through February. In other years, neck bands were recorded on a weekly basis following reports of white-fronted geese arriving in the region. Statistical Analyses Latitude and longitude data were entered into a geographic information system; observations were subsequently mapped with the aid of this technology. We used each unique neck-banded goose to test for differences based on breeding- September 2003 Anderson and Haukos—Breeding ground affiliation of white-fronted geese staging in Texas TABLE 1—Number of white-fronted geese neckbanded on breeding grounds by year and observed (October to March) in the Winchester Lakes region of northwestern Texas, 1991 to 1998. Number of Banded birds Banding Number unique birds observed year neck-banded recorded (%) 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 Total 407 446 3,412 3,253 3,651 3,546 5,614 2,947 1,272 24,548 3 0 73 60 105 149 334 66 7 797 0.74 0.00 2.14 1.84 2.88 4.20 5.95 2.24 0.55 3.25 ground affiliation of birds observed in the Winchester Lakes region. We determined wintering-ground affiliation (farthest south observation) on birds for which there were multiple observations from the same winter. We used contingency tables with a Gtest (Sokal and Rohlf, 1995) to test for differences in frequency of occurrence of neck-collared geese (number observed and number banded) on breeding and wintering areas. We set a 5 0.05 to test overall significance of a test and a 5 0.01 to test for differences between pairs of factors following a significant overall test. RESULTS Seven hundred ninety-seven neckbanded white-fronted geese were observed between 1991 and 1998 in the Winchester Lakes region of northwestern Texas (Table 1; Fig. 1). These birds were observed 4,266 times at Winchester Lakes and other areas throughout North America. Eighty birds (10.04%) were observed at the Winchester Lakes region during more than 1 winter. Four white-fronted geese were observed in 3 successive years. Five geese were observed twice, with the second observation occurring 4 years after the first. Approximately 80% of neck-banded whitefronted geese observations occurred from late January through February, but more than 100 observations were recorded during late November (Fig. 2). Birds typically arrived in the Winchester Lakes region during the fall migration after stopping in Nebraska, with observation in Winchester Lakes peaking during late November. Most birds left the Winchester Lakes region in early December, continuing 367 south to winter in the Texas rice prairies, Louisiana, and Mexico. During the northward migration, white-fronted geese increased in abundance in the Winchester Lakes region from early January through February (Fig. 2). Most birds left before March and were recorded in Nebraska within 2 weeks after their last observation at Winchester Lakes. Anser albifrons frontalis neck-banded in Alaska comprised 69% of the unique neck-banded geese observed in the Winchester Lakes region. Frequency of neck-banded white-fronted geese differed among banding areas (G5 5 890.5, P , 0.001; Table 2). About 9% of birds neck-banded in interior Alaska and in the Yukon area of Old Crow Flats were observed in the Winchester Lakes region (Fig. 3), but only 0.5% of Inglis River birds (eastern-most Arctic banding location) were observed (Table 2). Most of the birds banded in Alaska and recorded in the Winchester Lakes region were from Innoko National Wildlife Refuge (55.7%), but Koyukuk (17.9%), Kanuti (13.2%), and Selawik (10.1%) national wildlife refuges, and the Colville River Delta (2.9%) also were represented. Overall, 3.3% of the 24,548 white-fronted geese banded on 6 Arctic breeding areas from 1988 to 1996 were observed in the Winchester Lakes region. There were 59 neck-banded white-fronted geese (7.4% of recorded banded birds) observed in both the Winchester Lakes region and Mexico (Table 3). The frequency of neckbanded white-fronted geese observed in Mexico and associated with the Winchester Lakes region differed among banding areas (G5 5 12.8, P 5 0.02). The highest proportion of neck-banded white-fronted geese observed in Mexico and northwestern Texas were from the Queen Maud Gulf and Yukon (Old Crow Flats) areas (Table 3). Almost 13% of Queen Maud Gulf birds seen at Winchester Lakes were also seen in Mexico, but only 1 Central Arctic West bird was observed in both localities. The largest number of white-fronted geese seen in Winchester Lakes and Mexico were from Alaska, primarily from Innoko (65.2%) and Selawik (13.0%) national wildlife refuges. There were no Inglis River birds observed in both Mexico and the Winchester Lakes region. Based on 4,266 observations of 797 unique 368 The Southwestern Naturalist vol. 48, no. 3 FIG. 1 Location of 4,266 observations of neck-banded white-fronted geese from 6 breeding locations associated with the Winchester Lakes region of northwestern Texas, 1991 to 1998. white-fronted geese observed in the Winchester Lakes region, 77.4% and 7.4% of these individual birds were also seen in Canada and Mexico, respectively (Table 4). Observations of individual birds recorded from the Winchester Lakes region were primarily in Alberta (36.3%), Saskatchewan (67.4%), Nebraska (35.6%), and Texas rice prairies (21.3%). September 2003 Anderson and Haukos—Breeding ground affiliation of white-fronted geese staging in Texas 369 FIG. 2 Temporal distribution of observations (2-week intervals) for neck-banded white-fronted geese in Winchester Lakes region of northwestern Texas, 1991 to 1998. TABLE 2—Breeding ground affiliation of neckbanded white-fronted geese observed (October to March) in the Winchester Lakes region of northwestern Texas, 1991 to 1998. Neck-banded geese observed Banding area Interior Alaska Yukon (Old Crow Flats) Anderson River Queen Maud Gulf Central Arctic West Inglis River Totals Total banded Observed (num(num- Observed ber) ber) (%)1 5,799 323 5,668 5,933 4,173 2,652 24,548 545 27 134 48 31 12 797 9.40a 8.36a 2.36b 0.80c 0.74c 0.45c 3.25 1 Same letter following percentage indicates no difference (a 5 0.01) based on G-test. Eighty birds observed in the Winchester Lakes region were encountered again during the same winter (October through March). These birds wintered primarily in the Texas rice prairies (53), with many traveling to interior Mexico (17) and Louisiana coast (5). There seems to be a regular exchange of whitefronted geese between northwestern Texas and the rice prairies of Texas, because several birds were observed multiple times at each location during the same winter. Approximately 6% of the individual neck-banded white-fronted geese were observed each month in the Winchester Lakes region, indicating some use of the area as a wintering area. DISCUSSION The Winchester Lakes region of northwestern Texas serves primarily as a staging area for spring and fall migrants of the midcontinent population of greater whitefronted geese. Birds staging in the Winchester Lakes region predominately winter in Mexico and the rice prairies of the Texas Gulf Coast 370 The Southwestern Naturalist vol. 48, no. 3 FIG. 3 Location of 2,989 observations of neck-banded white-fronted geese from interior Alaska and associated with Winchester Lakes region of northwestern Texas, 1991 to 1998. September 2003 Anderson and Haukos—Breeding ground affiliation of white-fronted geese staging in Texas TABLE 3—Breeding ground affiliation of neckbanded white-fronted geese observed (October to March) in both Mexico and Winchester Lakes region of northwestern Texas, 1991 to 1998. Neck-banded geese observed Banding area Queen Maud Gulf Yukon (Old Crow Flats) Interior Alaska Central Arctic West Anderson River Inglis River Total Texas Mexico (num- (number) ber) 48 27 545 31 134 12 797 6 3 46 1 3 0 59 Mexico (%)1 12.50a 11.11a 8.44b 3.23bc 2.24c 0.00c 7.40 1 Same letter following percentage indicates no difference (a 5 0.01) based on G-test. 371 region. During spring migration, white-fronted geese observed in the Winchester Lakes region travel to the Rainwater Basins of Nebraska and then onward to the prairies of southern Saskatchewan and Alberta prior to traveling to their respective breeding grounds. Decisions regarding length of hunting seasons and associated harvest limits for northwestern Texas must consider the status of white-fronted geese from Interior-Northwest Alaska, Yukon, and Anderson River areas (western portion of midcontinent population). Status of populations from the Anderson River area and Koyukuk National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska should receive additional consideration, as white-fronted geese from these areas tend to be winter residents in the Winchester Lakes region. Although use varies by breeding area, the Winchester Lakes region provides habitat for a significant portion of the midcontinent population of greater white-fronted geese. Addition- TABLE 4—Number of neck-banded white-fronted geese observed by state or province that occurred (October to March) in Winchester Lakes Region of northwestern Texas, 1991 to 1998. Area Canada Alberta Northwest Territory Saskatchewan 1,913 480 2 1,431 44.84 11.25 0.05 33.54 617 289 2 537 77.42 36.26 0.25 67.38 78 3 18 48 9 1.83 0.07 0.42 1.13 0.21 59 3 17 32 9 7.40 0.38 2.13 4.02 1.13 Mexico Chihuahua Durango Tamaulipas Zacatecas Observations by area (%) Number of unique individuals Number of observations Individuals by area (%) United States Alaska Arkansas California Colorado Kansas Louisiana Missouri Nebraska North Dakota Oklahoma South Dakota Texas (Rice Prairies) (Winchester Lakes) 2,275 19 3 1 2 65 48 1 515 17 48 18 53.33 0.45 0.07 0.02 0.05 1.52 1.13 0.02 12.07 0.40 1.13 0.42 797 19 3 1 2 48 31 1 284 16 22 15 100.00 2.38 0.38 0.13 0.25 6.02 3.89 0.13 35.63 2.01 2.76 1.88 273 1,265 6.40 29.65 170 797 21.33 100.00 Totals 4,266 100.00 797 100.00 372 The Southwestern Naturalist al investigations should delineate white-fronted goose-habitat relationships in the Winchester Lakes region and assess effects of hunter harvest and other mortality factors in the region on the various breeding populations to better manage geese using the area. We thank J. Haskins and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (Region 2) for providing funding to complete the study. D. Nieman and K. Meeres, Canadian Wildlife Service, assisted in procuring neck-band data. L. Smith, R. Cox, Jr., R. Malecki, and J. Ray provided critical reviews of the manuscript. I. M. Ortega provided the Spanish translation of the abstract. LITERATURE CITED BELLROSE, F. C. 1980. Ducks, geese and swans of North America, third edition. Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. ELY, C. R., AND A. X. DZUBIN. 1994. Greater whitefronted goose (Anser albifrons). In: Poole, A., and F. Gill, editors. The birds of North America, number 131. Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, and American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C. ELY, C. R., AND J. A. SCHMUTZ. 1999. Characteristics vol. 48, no. 3 of midcontinent greater white-fronted geese from interior Alaska: distribution, migration ecology, and survival. Central Flyway Report, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Denver, Colorado. HAUKOS, D. A. 2001. Analyses of selected mid-winter waterfowl survey data (1955–2000): Region 2 (Central Flyway). United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Albuquerque, New Mexico. KING, J. G., AND D. V. DERKSEN. 1986. Alaska goose populations: past, present, and future. Transactions of the North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference 51:464–479. SOKAL, R. R., AND F. J. ROHLF. 1995. Biometry, third edition. W. H. Freeman and Company, New York. SPINDLER, M. A., J. M. LOWE, AND J. Y. FUJIKAWA. 1999. Trends in abundance and productivity of whitefronted geese in the taiga of northwestern and interior Alaska. Central Flyway Report, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Denver, Colorado. SULLIVAN, B. 1998. Management plan for midcontinent greater white-fronted geese. Central Flyway Report, United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Denver, Colorado. Submitted 31 May 2000. Accepted 12 July 2002. Associate Editor was William H. Baltosser.