CYNOMYS LUDOVICIANUS

advertisement

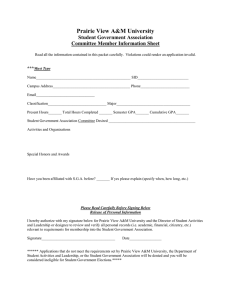

CONSERVATION OF BLACK-TAILED PRAIRIE DOGS (CYNOMYS LUDOVICIANUS) Author(s): Sterling D. Miller and Jack F. Cully Jr. Source: Journal of Mammalogy, 82(4):889-893. 2001. Published By: American Society of Mammalogists DOI: 10.1644/1545-1542(2001)082<0889:COBTPD>2.0.CO;2 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1644/15451542%282001%29082%3C0889%3ACOBTPD%3E2.0.CO%3B2 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is an electronic aggregator of bioscience research content, and the online home to over 160 journals and books published by not-for-profit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Mammalogy, 82(4):889–893, 2001 CONSERVATION OF BLACK-TAILED PRAIRIE DOGS (CYNOMYS LUDOVICIANUS) STERLING D. MILLER* AND JACK F. CULLY, JR. National Wildlife Federation, Northern Rockies Project Office, 240 North Higgins, Suite #2, Missoula, MT 59802 (SDM) United States Geological Survey, Kansas Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Division of Biology, Kansas State University, Manhattan, KS 66504 (JFC) ‘‘. . . discovered a Village of Small animals that burrow in the grown (those animals are Called by the french Petite Chien) . . . we found 2 frogs in the hole and Killed a Dark rattle Snake near with a Ground rat [prairie dog] in him . . . Those Animals are about the Size of a Small Squ[ir]el . . . much resembling a Squirel in every respect . . . his tail like a ground squirel which they shake and whistle when allarmd . . . it is Said that a kind of Lizard also a Snake reside with those animals.’’ (Meriwether Lewis, Lewis and Clark Expedition, 17 September 1804) Key words: conservation, Cynomys ludovicianus, Endangered Species Act, plague, prairie dogs On his voyage of discovery up the Missouri River, across the Rocky Mountains, down the Columbia River, and back, Meriwether Lewis catalogued many new species. One of those was the black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus), which the Lewis and Clark Expedition found to be abundant in many places along their route to the Rocky Mountains. Two hundred years later, modern travelers along this same route are almost as unlikely to encounter prairie dogs as they are to encounter wolves (Canis lupus), bison (Bison bison), or grizzly bears (Ursus arctos), species that currently are functionally extinct on the Great Plains. The habitat of the prairie dog has been fragmented and converted to croplands and pastures (Hoogland 1995; Mac et al. 1998). Numbers of prairie dogs have been decimated by poisoning campaigns designed to reduce suspected competition with livestock and an exotic disease, sylvatic plague (Yersinia pestis—Cully and Williams 2001; S. Forrest et al., in litt.; Hoogland 1995). The huge colonies in which prairie dogs evolved are now gone (Hoogland 1995; Miller et al. 1996). In terms of the role of the prairie dog in maintaining the biodiversity of prairie ecosystems, the prairie dog may be as functionally extinct as the bison (M. Gilpin, pers. comm.). The paucity of large prairie dog colonies bodes ill for the conservation of associated species such as black-footed ferrets (Mustela nigripes), ferruginous hawks (Buteo regalis), mountain plovers (Charadrius montanus), and burrowing owls (Athene cunicularia). Although he was not familiar with the term keystone, the ever-observant Meriwether Lewis noted numerous creatures that were associated intimately with prairie dogs. More recently, the status of prairie dogs as a keystone species of prairie ecosystems has been confirmed (Kotliar 2000; Kotliar et al. 1999; Miller et al. 1994, 2000; cf. Stapp 1998 for a different perspective). Five species of prairie dogs occur in North America (Fig. 1) and all suffer to different degrees from the same problems of mismanagement or plague as the black- * Correspondent: millerS@nwf.org 889 890 JOURNAL OF MAMMALOGY FIG. 1.—The historical geographic ranges of the 5 recognized species of prairie dogs (based on Miller et al. 1996). tailed prairie dog. The Utah prairie dog (C. parvidens) was listed as endangered in 1973, and that classification was changed to threatened in 1984, although the status of the species remains precarious (United States Fish and Wildlife Service 1991; M. Ritchie, in litt.). The Mexican prairie dog (C. mexicanus) inhabits northeastern Mexico and was listed as endangered in 1970 (Miller et al. 1996), before passage of the Endangered Species Act. Gunnison’s (C. gunnisoni) and white-tailed (C. leucurus) prairie dogs are geographically more restricted in range than black-tailed prairie dogs (Hoogland 1996). White-tailed prairie dogs live in less dense colonies that may be more resilient to plague, but Gunnison’s prairie dogs may be even more susceptible to plague than black-tailed prairie dogs (Cully and Williams 2001). Numerically, the most abundant of prairie dog species is the black-tailed prairie dog, which inhabits Vol. 82, No. 4 mixed-grass and short-grass prairies of North America east of the continental divide from southern Saskatchewan, Canada, to northern Mexico. No good estimate of total numbers of prairie dogs is available, although the number of black-tailed prairie dogs is in the millions. Prairie dog abundance usually is expressed in terms of surface area occupied by their colonies. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service estimated that about 159.4 million ha of potential habitat existed in the United States, but only about 20% (78.7 million ha) was occupied at any one time (Gober 2000). Less than 0.4 million ha of habitat are currently occupied (Gober 2000), ,1% of historically occupied habitat. This decline, and other factors, led the National Wildlife Federation to file its 1stever petition to list a species under the Endangered Species Act. In 1998, the National Wildlife Federation filed a petition to list black-tailed prairie dogs as threatened (Graber et al. 1998; Van Putten and Miller 1999). The National Wildlife Federation petition claimed that listing was warranted under at least the first 4 of the 5 requirements for listing (only 1 is required for listing under the Endangered Species Act; United States Code Title 16 §1533): 1) present or threatened destruction, modification, or curtailment of habitat; 2) overutilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes; 3) disease or predation; 4) inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms; and 5) other natural or man-made factors affecting its continued existence. Many of the same concerns expressed in the National Wildlife Federation petition were expressed in a ‘‘Resolution on the decline of prairie dogs and the grassland ecosystem in North America’’ adopted by the American Society of Mammalogists (American Society of Mammalogists 1998) and a resolution on ‘‘Conservation of Prairie-dog Ecosystems’’ (Society for Conservation Biology, in litt.). In February 2000, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service responded to the pe- November 2001 SPECIAL FEATURE—PRAIRIE DOGS tition by the National Wildlife Federation by finding that the species was warranted for listing but currently precluded because of higher priority threats facing other species and shortage of funds (Gober 2000). This warranted-but-precluded finding classified prairie dogs as a candidate for listing and mandated that the Fish and Wildlife Service conduct an annual status review to see if the species should be listed, removed from the candidate list, or retained on this list. During the period the Fish and Wildlife Service was considering the petition, all 11 states within the current or former range of the black-tailed prairie dog either initiated or accelerated their efforts to develop management plans for the species. During 1999, 9 of those states signed an agreement designed to provide guidelines for management and conservation of prairie dogs and other species associated with prairie dog colonies (only Colorado and North Dakota did not sign). As part of this coordinated effort, the states appointed an Interstate Coordinator of the Black-tailed Prairie Dog Conservation Team, Bob Luce from Rock Springs, Wyoming, to coordinate the states’ management planning efforts. States that are part of the collaborative effort have agreed that their prairie dog management plans should be in place by October 2001. Much of the accelerated planning effort by the states was motivated by the states’ desire to avoid a federal listing of the species. Unlike a ‘‘non-warranted’’ finding, the warranted-but-precluded finding retains an incentive for the states to improve the status of prairie dog management and implement their plans and agreements. If the Fish and Wildlife Service decides that the species needs to be listed after 1 of the annual reviews, the states with an acceptable prairie dog management plan possibly could be exempted from federal management through a ‘‘Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances.’’ Those agreements would specify conservation actions that the states would take and would provide assurances 891 that as long as the agreement was followed by a state, that state could continue its management even if the species was listed (P. Gober, pers. comm.). As part of the petition review process, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service initiated a population viability analysis and contracted with M. Gilpin of the University of California, San Diego, to conduct the viability study. A team of prairie dog experts met to provide input into this population viability analysis. That team had several meetings culminating in a conference that was held in Phoenix, Arizona, in December 1999. This special feature on prairie dogs incorporates a selection of those presentations. The papers at the conference addressed all of the criteria, enumerated above, for listing under the Endangered Species Act, but not all of those papers are presented here. Emphasis in this special feature is on the most important factors influencing prairie dog persistence. Cully and Williams (2001) present information on the devastating impacts of plague on North American prairie dogs and speculate on the configuration of prairie dog towns most likely to persist on future landscapes. Biggins and Kosoy (2001) contrast the relatively moderate impacts of plague on Asian rodents and mustelids that coevolved with plague to the more severe impacts of plague found in ecologically similar species in North American that have only relatively recent exposure to plague. Habitat fragmentation and the importance of anthropogenic activities on colony size and probability of persistence on the southeastern edge of prairie dog range are examined by Lomolino and Smith (2001). Roach et al. (2001) used genetic markers to describe dispersal patterns in a complex of colonies in northern Colorado and discuss the pertinence of their findings to colony persistence. Interspecific comparisons based on field studies of reproductive biology of 3 species of prairie dogs are presented by Hoogland (2001). Hoogland’s studies demonstrate that prairie 892 JOURNAL OF MAMMALOGY dogs have lower intrinsic rates of increase and are consequently more vulnerable to colony extinction than are most rodents. Finally, Sidle et al. (2001) present new estimates of prairie dog abundance in 4 states that are critically important to conservation of prairie dogs. Their paper presents a new aerial survey technique for abundance estimation that is replicable, includes estimates of precision, and does not require trespass permission from private landowners. A previously published paper on the effects of recreational shooting on prairie dogs (Vosburg and Irby 1998) also was presented at the conference. Additional important information was presented at the conference that is not included in this special feature. These included a historical analysis of prairie dog poisoning campaigns on federal lands (S. Forrest et al., Haylite Consulting, Bozeman, Montana), a review of prairie dog genetics and phylogeography (M. Antolin et al., Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado), and an analysis of techniques for creating new prairie dog colonies by translocation (J. Truett et al., Turner Endangered Species Fund, Glenwood, New Mexico). We hope that this special feature will direct attention to the plight of prairie dogs and the ecosystems in which they play a keystone role. All of the states within the range of the prairie dog have statutes classifying the species as a pest or varmint, and no state has adequate regulatory mechanisms in place to assure conservation of this species within its borders (Gober 2000; Graber et al. 1997; Van Putten and Miller 1999). By itself, the impacts of a century of prairie dog mismanagement may be reversible with implementation of more ecologically based management programs; however, recovery is made more problematic because of the presence of plague. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank B. Van Pelt and the Arizona Game and Fish Department for hosting the conference Vol. 82, No. 4 at which these manuscripts and others were presented. We thank P. Gober of the Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Wildlife Federation for facilitating travel of participants to the conference. M. Gilpin, University of California, San Diego, conducted the population viability analysis, which was based on many of the ideas and concepts presented at the conference. We are grateful to all who made presentations at this conference, including those that are not included in this special feature. We thank M. Willig for his interest in and efforts on behalf of this special feature. LITERATURE CITED AMERICAN SOCIETY OF MAMMALOGISTS. 1998. American Society of Mammalogists’ resolution on the decline of prairie dogs and the grassland ecosystem in North America. Journal of Mammalogy 79:1447– 1448. BIGGINS, D. E., AND M. Y. KOSOY. 2001. Influences of introduced plague on North American mammals: implications from ecology of plague in Asia. Journal of Mammalogy 82:906–916. CULLY, J. F., JR., AND E. S. WILLIAMS. 2001. Interspecific comparisons of sylvatic plague in prairie dogs. Journal of Mammalogy 82:894–905. GOBER, P. 2000. 12-Month administrative finding, black-tailed prairie dog. Federal Register 65:5476– 5488. GRABER, K., T. FRANCE, AND S. MILLER. 1998. Petition for rule listing the black-tailed prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus) as threatened throughout its range. National Wildlife Federation, Boulder, Colorado. HOOGLAND, J. L. 1995. The black-tailed prairie dog: social life of a burrowing mammal. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois. HOOGLAND, J. L. 1996. Cynomys ludovicianus. Mammalian Species 535:1–10. HOOGLAND, J. L. 2001. Black-tailed, Gunnison’s, and Utah prairie dogs reproduce slowly. Journal of Mammalogy 82:917–927. KOTLIAR, N. B. 2000. Application of the new keystonespecies concept to prairie dogs: how well does it work? Conservation Biology 14:1715–1721. KOTLIAR, N. B., B. W. BAKER, A. D. WHICKER, AND G. PLUMB. 1999. A critical review of assumptions about the prairie dog as a keystone species. Environmental Management 24:177–192. LOMOLINO, M. V., AND G. A. SMITH. 2001. Dynamic biogeography of prairie dog (Cynomys ludovicianus) towns near the edge of their range. Journal of Mammalogy 82:937–945. MAC, M. J., P. A. OPLER, C. E. PUCKETT HAECKER, AND P. D. DORAN. 1998. Status and trends of the nation’s biological resources. United States Department of the Interior, United States Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia 2: 437–964. MILLER, B., G. CEBALLOS, AND R. READING. 1994. The prairie dog and biotic diversity. Conservation Biology 8:677–681. November 2001 SPECIAL FEATURE—PRAIRIE DOGS MILLER, B., ET AL. 2000. The role of prairie dogs as keystone species: a response to Stapp. Conservation Biology 14:318–321. MILLER, B., R. P. READING, AND S. FORREST. 1996. Prairie night: black-footed ferrets and the recovery of endangered species. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C. ROACH, J. L., P. STAPP, B. VAN HORNE, AND M. F. ANTOLIN. 2001. Genetic structure of a metapopulation of black-tailed prairie dogs. Journal of Mammalogy 82:946–959. SIDLE, J. G., D. H. JOHNSON, AND B. R. EULISS. 2001. Estimated areal extent of colonies of black-tailed prairie dogs in the northern Great Plains. Journal of Mammalogy 82:928–936. 893 STAPP, P. 1998. A reevaluation of the role of prairie dogs in Great Plains grasslands. Conservation Biology 12:1253–1259. UNITED STATES FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE. 1991. Utah prairie dog recovery plan. United States Fish and Wildlife Service, Denver, Colorado. VAN PUTTEN, M., AND S. D. MILLER. 1999. Prairie dogs: the case for listing. Wildlife Society Bulletin 27:113–120. VOSBURGH, T. C., AND L. R. IRBY. 1998. Effects of recreational shooting on prairie dog colonies. The Journal of Wildlife Management 62:363–372. Special Feature Editor was Michael R. Willig.