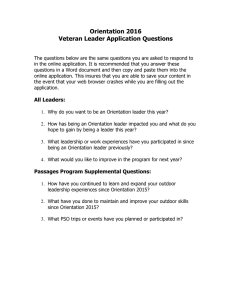

C O M M I S S I O N...

advertisement