Chapter 112 White Collar Crime I.

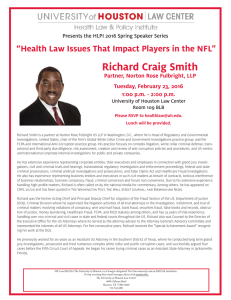

advertisement