Document 13000778

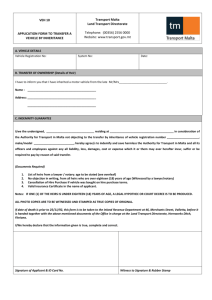

advertisement