Document 13000777

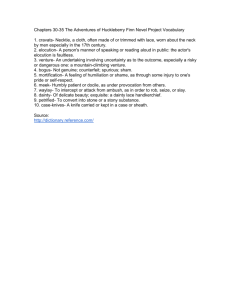

advertisement