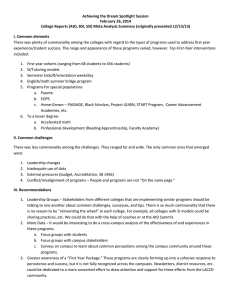

Using student voices to redefine support Student Support defined

advertisement