LLB Options Booklet 2015-16

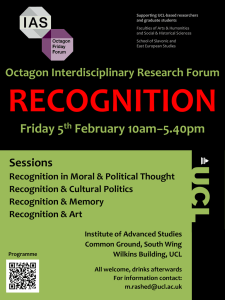

advertisement