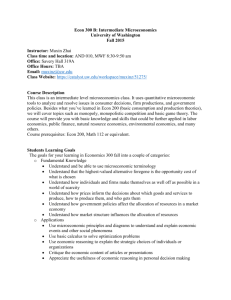

CLES

advertisement