CLES

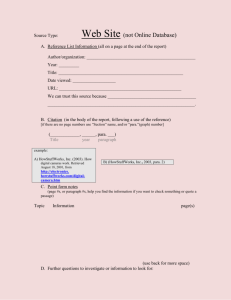

advertisement