for the presented on (Degree) (Major)

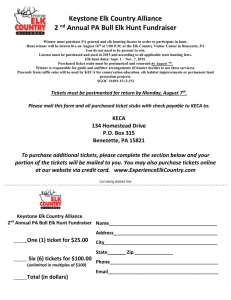

advertisement