Joint inspection of services to protect children and April 2009

advertisement

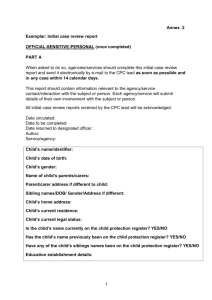

Joint inspection of services to protect children and young people in the Fife Council Area April 2009 Contents Page Introduction 1 1. Background 2 2. Key strengths 3 3. How effective is the help children get when they need it? 4 4. How well do services promote public awareness of child protection? 7 5. How good is the delivery of key processes? 8 6. How good is operational management in protecting children and meeting their needs? 13 7. How good is individual and collective leadership? 15 8. How well are children and young people protected and their needs met? 18 9. What happens next? 19 Appendix 1 Indicators of quality 20 Appendix 2 Examples of good practice 21 How can you contact us? 22 Introduction The Joint Inspection of Children’s Services and Inspection of Social Work Services (Scotland) Act 2006, together with the associated regulations and Code of Practice, provide the legislative framework for the conduct of joint inspections of the provision of services to children. Inspections are conducted within a published framework of quality indicators, ‘How well are children and young people protected and their needs met 1?’ Inspection teams include Associate Assessors who are members of staff from services and agencies providing services to children and young people in other Scottish local authority areas. 1 ‘How well are children and young people protected and their needs met?’. Self-evaluation using quality indicators, HM Inspectorate of Education 2005. 1 1. Background The inspection of services to protect children2 in the Fife Council area took place between October and November 2008. It covered the range of services and staff working in the area who had a role in protecting children. These included services provided by health, the police, the local authority and the Scottish Children’s Reporter Administration (SCRA), as well as those provided by voluntary and independent organisations. As part of the inspection process, inspectors reviewed practice through reading a sample of files held by services who work to protect children living in the area. Some of the children and families in the sample met and talked to inspectors about the services they had received. Inspectors visited services that provided help to children and families, and met users of these services. They talked to staff with responsibilities for protecting children across all the key services. This included staff with leadership and operational management responsibilities as well as those working directly with children and families. Inspectors also sampled work that was being done in the area to protect children, by attending meetings and reviews. As the findings in this report are based on a sample of children and families, inspectors cannot assure the quality of service received by every single child in the area who might need help. Fife is situated on the east coast of Scotland. It covers 1,325 kilometres and lies between the River Tay to the north and the River Forth in the south. Fife has retained the same council boundaries through consecutive local government reorganisations. Fife Constabulary, NHS Fife and Fife Council have the same administrative boundaries. The main towns in Fife are Glenrothes, Kirkcaldy, Dunfermline, Cowdenbeath and St Andrews. The administrative centre is Glenrothes. With a population of 358,930, Fife is the third largest local authority in Scotland. Unemployment rates in 28% of council wards are more than twice the national average. In 2006, the percentage of the population under 18 years was 20.8% which was slightly higher than the national figure of 20.5%. The incidence rate of domestic abuse in Fife in 2006 was higher than Scotland as a whole. At the end of 2007, 496 children had been referred for child protection enquiries representing an increase of 63% over the previous year. This was significantly higher than increases in comparator authorities3 at 11.1% and nationally at 13.6%. 2 3 2 Throughout this document ‘children’ refers to persons under the age of 18 years as defined in the Joint Inspection of Children’s Services and Inspection of Social Work Services (Scotland) Act 2006, Section 7(1). Comparator authorities include South Lanarkshire Council, Falkirk Council, Clackmannanshire Council, West Lothian Council and Renfrewshire Council. 2. Key strengths Inspectors found the following key strengths in how well children were protected and their needs met in Fife Council area. • The effective help and support provided by health staff to vulnerable pregnant women and their babies, particularly those affected by substance misuse. • The extensive range of helpful material promoting awareness of child protection in staff and the general public. • The increasing use of Family Group Conferences to explore all options for children at risk of being accommodated away from home. • ‘The Big Shout’ had created a valuable opportunity for children to contribute to policy development and as a result the confidence and self-esteem of those taking part had increased. 3 3. How effective is the help children get when they need it? Children knew who to go to if they needed help. Children and families had regular contact from staff across services. Children were helped by support from a range of specialist services. The availability of services to support families was inconsistent and there was no clear strategy for commissioning or compensating for gaps. Staff responded promptly to clear and identified risk of harm to children. They were often slow to respond when the need was less urgent. Frequently, action did not take place until a child’s situation was critical and problems deep-rooted. Long periods of involvement with services did not always improve the lives of children. Being listened to and respected Communication between staff, children and families was satisfactory. Staff built trusting relationships with children and families. School staff knew children well. Health staff had regular contact with younger children and carefully observed changes in their health and behaviour. Staff in voluntary services spent time with children and got to know them well. Social workers had very frequent contact with children, particularly when they were on the Child Protection Register (CPR). However, staff did not always explain adequately the purpose of contact and families did not always know the reasons for visits or understand why there were concerns. Although social workers visited children frequently, insufficient time was spent with individual children. This made it difficult to find out what children had to say about their circumstances. When children had communication difficulties, some staff used a range of measures to help them make their opinions known. Staff had easy access to interpreting services and used them appropriately. Communication with children at formal meetings was variable. At some meetings communication was clear and effective. Time was taken to ensure that children and families understood what was happening and they were supported to express their opinions. However, not all staff routinely considered the views of children and families or took time to prepare them for attendance at meetings. Some children were not given sufficient opportunity in formal meetings to express their views. When children and families did not attend meetings, staff did not always pass on the views of children adequately. It was not normal practice for the chair of the meeting or other managers to meet non-attending families and convey the decisions of the meeting or explain what would happen next. Children’s Panel members consistently sought the views of children at hearings. Social work staff did not always support children sufficiently to complete Having Your Say forms. Being helped to keep safe The effectiveness of services to help keep children safe was satisfactory. Services to support children and families were distributed unevenly across the area. There was no consistent approach used across Fife to deliver parenting support. For example, Homestart staff and volunteers supported families practically and emotionally in several areas of Fife. In the Kirkcaldy area Barnardo’s ‘Family Matters’ used a range of parenting approaches such as Mellow Parenting effectively. 4 Overall, a number of key services in the voluntary sector were commissioned for delivery in specific localities, denying access to some families out with these areas and potential removal of service if a family moved home. There was not a consistent approach to delivering parenting support to families. Pre-school centres offered effective support to vulnerable children. However, some children could only receive a place outwith their home area. There was no overarching early year’s strategy. Waiting lists for access to some services, such as The Cottage Centre, were lengthy. Almost all child care services were not able to support families in the evening or weekends. Social workers were unable to use home care services to support children and families. There was no strategic approach to commissioning of services from the voluntary sector. The Vulnerable in Pregnancy (VIP) midwives supported a large number of vulnerable women through pregnancy and several weeks following delivery. Children received a wide range of informative materials from school, police and health staff about personal safety. A variety of programmes helped raise children’s awareness, promote their safety and help them improve relationships. Overall, children found information on personal safety helpful. Community police helpfully visited schools and spoke to children on a range of relevant subjects. ‘Boozebusters’ helped children understand alcohol through drama and workshops and develop strategies to cope if misuse affected their lives. ‘Cool in School’ successfully helped children develop positive ways of managing relationships. Children’s home circumstances were actively considered before any decision was taken to exclude them from school. The existing council policy on educating children at home was being updated appropriately in line with Scottish Government advice. There were effective procedures in place for dealing with children absent from school without explanation or reported as missing. Staff involved had a good understanding of their roles and responsibilities. Almost all children could identify someone outside their family they could go to for help with a problem. They expressed confidence in guidance staff, school nurses and community police officers. Children had access to relevant telephone numbers, including ChildLine, which were pre-printed in homework planners. They were confident about how to keep safe when using the Internet and mobile phones. Children knew about the bullying policies in their schools and were clear about approaches to resolving conflict. Parents, who responded to school inspection questionnaires, felt staff showed concern for the care and welfare of their child, treated them fairly and would act on a concern raised. Some examples of what children said about keeping themselves safe. “Ms X knows everybody. She is really good, easy to talk to and has always got time.” “They should put more CCTV up and have curfews.” “Our school nurse is really kind, really nice. You know she will understand.” “We are always being given this kind of information at registration.” 5 Immediate response to concerns The immediate response to concerns was weak. When staff had concerns about children’s safety or welfare they quickly reported their concerns to police or social work services. Overall, social workers took immediate steps to protect children when there were clear and identified risks. They made effective use of Child Protection Orders to remove children to a safe place. They ensured that unborn babies who were known to be at risk were protected as soon as they were born. However, there were important weaknesses. Staff were often slow to respond, particularly to children who were at risk of neglect. Situations often escalated to a crisis point before effective action was taken. Some children experienced delays before they received the help they needed. These children were left feeling unsafe and unsure about what was going to happen. It was difficult to find temporary foster placements for some children out-of-office hours. There were examples of children left for periods in police stations until appropriate care was found. In most, but not all cases, staff carried out checks on the suitability of relatives and friends when they made arrangements for children to be cared for in an emergency. In a few cases, these checks were carried out but not properly recorded. A few children remained in circumstances which continued to place them at risk. Meeting needs Overall, meeting children’s needs was weak. Some children identified as at risk of abuse or for whom concerns had been raised received effective support. They had their needs met and as a result their lives improved. Some staff across services worked well together to help meet children’s needs. However, some did not get the help they needed and support for vulnerable children across the Fife Council area lacked a coordinated approach. The immediate and short term needs of children were met more effectively than their longer term needs. There were significant delays in progressing plans for the longer term future of some vulnerable children. Some children and their parents benefited in the short term from a range of support services, including those provided by the voluntary sector. However, practice to support families varied across the Fife Council area and the needs of vulnerable children were not always met. Staff from different services worked skilfully together to meet the needs of children with complex health or additional support needs. Families who required sustained support over a prolonged period of time did not always receive this. Support to families reduced when children were removed from the CPR. A shortage of foster placements meant that a few children had to move several times as suitable carers were not available or remain in situations where their needs were not being met. Some children did not have their individual needs met when they were part of a family group. The situations of some children did not improve despite long periods of involvement with services. Vulnerable children, including those whose sexual behaviour posed risks to themselves and others, were helped effectively by specialist services, such as the Child Support Service, educational psychologists and the Centre for the Vulnerable Child. Some children had to wait a considerable time before receiving specialist help. There was no Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services support out-of-office hours, resulting in a few children being placed inappropriately in hospital 6 in an emergency and treated by psychiatric staff who worked with adults. Women’s Aid children’s workers worked well with children affected by domestic abuse. 4. How well do services promote public awareness of child protection? The Child Protection Committee (CPC) had developed informative materials to promote child protection, which were widely available. Services were available which allowed the public to report concerns about child protection at all times. The social work Emergency Out of Hours Service (EOOHS) was not always able to respond appropriately to reported concerns. Being aware of protecting children The approaches taken to raise public awareness of child protection were good. The CPC had a clear communications strategy which gave a strong message that ‘child protection is everyone’s job...it’s our job’. This had been widely promoted and understood by staff. A wide range of eye catching information posters and leaflets had been produced. These were displayed prominently in public buildings and contained helpful information, including details of important contact points. The CPC had developed an easily recognisable logo which was visible on all child protection publicity materials. The CPC had created an effective website which was hosted on the Fife Council server and had links from the Fife Constabulary and NHS Fife websites. The informative Keep yourself safe Flip Fone had been distributed to a large number of children. There had been limited success in involving the local media to promote child protection. Concerns about children’s safety were reported by members of the public to staff in all services, particularly the police and social work services. Referrals, including those made anonymously, were given priority by police and social work staff and followed up appropriately and in good time. Specialist family protection police officers and social workers were available to receive concerns during office hours. In the evenings and at weekends call handling staff in the police contact centre referred calls about child protection to an appropriate officer. Calls to the social work EOOHS were routed through Fife Council Services Emergency Support Line and prompt contact was made to referrers. However, EOOHS was not always able to respond appropriately or provide a social worker with relevant child care experience to undertake investigations. There were no formal arrangements to ensure feedback was given routinely to members of the public who had raised concerns. 7 5. How good is the delivery of key processes? Services were inconsistent in ensuring the involvement of children and families in decision-making processes affecting their lives. Children received variable support to attend Children’s Hearings. While staff were aware of the need to share information, significant gaps in information had impacted adversely on the quality of risk assessment and planning for some vulnerable children. Social work and police worked well together to investigate when a child was at risk of abuse, but did not always involve health sufficiently early. There were significant weaknesses in assessments of risk and need. There was a lack of an integrated approach to planning for children. Planning for some children’s longer term needs was delayed. Involving children and their families The involvement of children and their families in key processes was weak. Practice across the Fife Council area varied significantly. Parents were routinely invited to child protection case conferences and invitations included informative leaflets outlining the process of the conference. Some children and families, including extended family members, were supported well to be involved in case conferences and other formal meetings where important decisions were made about them. They were encouraged to participate fully and the Chairperson ensured that the views of children and families were sought. However, families were not always prepared well to attend case conferences and reviews, or supported effectively to contribute meaningfully. Only a minority of children attended child protection case conferences. Reports were not consistently discussed with children and families in advance and were often issued to parents at meetings. Reviewing officers chairing case conferences did not routinely meet with parents or children prior to, or after meetings. As a result they were not prepared for them or supported to understand the decisions made and what would happen next. When families did not attend case conferences, there was no systematic approach to informing them of decisions. Most children and families attended looked after children’s reviews. Staff did not always ensure that children received sufficient encouragement and support to participate fully in such meetings. Some children and families were not adequately prepared or supported to attend Children’s Hearings. Procedures to have children excused from panels were not always followed. Advocacy services were available but their use was inconsistent. Priority was given to children who were looked after away from home. All families with children under the age of ten at risk of being looked after away from home, or for whom permanent plans were being considered for their future were referred to Children 1st for a Family Group Conference (FGC). Staff in Children 1st supported children and families well to prepare for, and participate in, FGC meetings. Easy to read leaflets advising people how to complain had been produced by services. However, they were not always visible in public buildings. Information about making a complaint about the quality of service was helpfully included on some websites. All services had clear written policies and procedures for dealing with formal complaints and expressions of dissatisfaction. This included timescales for responding. 8 Most services had arrangements in place to monitor and report on trends and how this could influence service development and review. Social work services had yet to establish a formal mechanism for monitoring and reporting on complaints received. Sharing and recording information The sharing and recording of information was weak. Almost all staff in agencies were aware of the need to share information and of its importance in protecting children. A joint practitioners’ and managers’ guide on information-sharing emphasised responsibility for sharing information and gave reassurance to staff on confidentiality. However, there was a lack of detailed support and guidance for staff to ensure consistency in information-sharing across agencies. Some key information, such as changes in family circumstances and children on supervision requirements, was not always passed to all relevant staff. At times, Information-sharing was too dependent on informal approaches and individual relationships. Particular features of information-sharing included the following: • effective information-sharing at case conferences and core group meetings; • improved multi-agency access to information through the 24-hour online CPR; • the Child Protection Messaging Alert System gave key staff improved information on child protection investigations, registrations and de-registrations. In some areas of health the system was not yet fully operational or effective; • some health and social work staff did not always understand the purpose and use made of information and the need for the information flow to be continued following referral; • sometimes school nurses did not receive information on vulnerable children or children on the CPR; • some social workers delayed returning calls to colleagues from other services wishing to discuss concerns about vulnerable children; • General Practitioners (GPs) were not routinely invited to attend child protection meetings; and • multiple health records in different locations presented a significant challenge to staff to ensure they had all relevant information on children for whom there may be child protection concerns. Recording in children’s files was variable. Social work recorded information electronically as well as in a paper system. Recording in social work files was organised effectively and historical information on families was included in reports. However, the information did not provide a usable or effective summary of significant 9 events in the child’s life which could help assessment and planning. Social work staff found the electronic recording system time consuming and unwieldy. Health and school files lacked organisation. Overall, the Children’s Reporter’s files were well structured and organised. Police information included a useful summary of historical involvement with cases. There were examples where key information was missing or incomplete in education, health and social work records. Practice in seeking and recording the consent of service users for the sharing of information was not well developed. Parents and families were not routinely advised of what information was being shared about them and with whom. Staff were aware of the need to obtain consent. Sometimes this happened verbally but it was not recorded consistently. Parents were unsure of the information being shared about them and their children. Recent guidance had clarified the position on disclosure of confidential information and staff were aware of the need to inform service users about information shared when consent had not been given. There was effective sharing and recording of information on sex offenders. Regular Multi-Agency Public Protection Arrangements (MAPPA) meetings were attended well by police, social work and housing staff, and provided an effective forum for exchanging information. Police officers had a good knowledge of the arrangements for sharing information and were aware of the need to manage the information on sex offenders effectively. Regular risk assessment meetings were held to monitor sexually aggressive children and those not covered by the MAPPA process. Police officers ensured information was recorded about individuals following an allegation of neglect or abuse, ensuring relevant information was available to Disclosure Scotland. Recognising and assessing risks and needs Recognition and assessment of risks and needs was weak. Staff in all services were alert to signs that children may need help or protection. This included staff who worked with adults and did not have a direct responsibility for children. However, staff were often unclear about how and when to use a variety of forms available to record and refer concerns about children. This included children who may be in need of immediate protection. An inter-agency agreement had been reached to carry out Initial Referral Discussions (IRDs) to gather information, conduct initial assessments of risks and plan joint investigations. Staff in police, social work, health and education were unsure about the purpose of IRDs and were inconsistent in how they used this process. Social work staff did not always initiate an IRD when they investigated concerns about a child as a single service. Police officers and social workers worked well to gather information and plan joint investigations. They did not always fully involve health staff at a sufficiently early stage to assist in decisions about whether a medical examination was necessary. Child Protection Case Conferences (CPCCs) were quickly and appropriately arranged for children who needed them. The creation of a multi-agency screening group to consider children for whom the police had cause for concern was being planned. The quality of assessments of risks and needs was variable. The Child Support Team completed thorough assessments of children who were displaying sexually inappropriate behaviour. Barnardo’s ‘Family Matters’ completed comprehensive 10 assessments of parenting and children’s needs. Health staff used a number of approaches to help identify children who may be in need of care and protection. Social workers had very recently started to use an initial assessment framework for all children and families who were referred. A small number of assessments by social workers were of a high quality. Most did not analyse the risks and needs of children sufficiently or present clear conclusions about the actions needed to safeguard children. Assessments did not focus sufficiently on the risks to and needs of individual children within a family grouping. Some overlooked the risks associated with neglect and possible sexual abuse. School nurses did not use a standard approach to health assessment suitable for working with children of school age. There was no tool to assist staff in the assessment of risks associated with domestic abuse. Social workers in EOOHS were unable to access completed assessments to help them to carry out their own assessments in emergency situations. There were a few children who were placed with kinship carers without sufficient assessment. Staff in social work and police worked well together to carry out joint investigations of child abuse. Overall, staff carefully planned joint investigations and they took good account of the child’s age and communication needs. However, for some children there were delays in joint investigations due to difficulties in identifying and releasing a suitably trained social worker. This was more difficult during evenings and weekends. There was a rota of paediatricians available to carry out medical examinations and, where appropriate, these were carried out jointly with experienced Forensic Medical Examiners. Children were examined in a child friendly environment and paediatricians ensured that children’s health needs were followed up. Staff assessed risks and needs of children affected by parental substance misuse without clear guidance or reference to the principles of ‘Getting Our Priorities Right’. A public health nurse assisted staff in addictions services with assessment of patients with dependent children. The VIP midwives identified effectively the needs of pregnant women with problem substance misuse at a very early stage. Together with the CPC, Fife Drug and Alcohol Team had plans to report on the numbers of children affected by parental substance misuse. A Practitioners’ Guide to working with families affected by parental substance was under development. Planning to meet needs The processes for planning to meet children’s needs were weak. Staff met regularly to plan how best to meet children’s needs. Reviewing officers, independent of the management of the case, chaired CPCCs, reviews and looked after children’s reviews. However, their authority to challenge staff practice across services, and their role in quality assurance was limited. Plans were often too broad, and did not reflect the particular needs of individual children within the family. They did not always give sufficient attention to what needed to improve in order to meet children’s needs. There were delays in planning for the longer term needs of some vulnerable children. Clear and effective planning at CPCCs helped some children. Most CPCCs and looked after children’s reviews were held promptly. Minutes of these meetings were 11 usually circulated in good time. Most initial CPCCs were well attended. Review case conferences, where important decisions about de-registration were taken, were less well attended. In a few cases only one agency was represented. Addictions staff rarely attended child protection meetings. GPs and school nurses were not routinely invited to meetings, leaving most school aged children without a named health professional to take responsibility for their health needs. The quality of child protection plans was variable. Many lacked detail, clear timescales, identification of a lead professional responsible for progressing actions or expected outcomes for children. For some children, plans did not reflect their individual needs. Plans did not sufficiently set out how identified risks would be reduced. Some children remained on the CPR for long periods with no improvement in their circumstances. The plans for some children remained the same over time and did not reflect changes in their circumstances. There were delays in planning to meet their longer term needs of some children. There were delays by Children’s Reporters in decision-making and in arranging children’s hearings. The quality of reports provided to the Children’s Reporter was variable and they did not always assist them to take timely decisions. Some hearings were postponed as reports were not available for the panel to consider. Overall, core groups took place for children on the CPR. Some parents and extended family attended these meetings. Meetings were used to share information and monitor developments in children and family’s circumstances. However, they did not focus sufficiently on evaluating progress of plans and reduction in the risks to each child. Core groups were now taking place regularly. The range of meetings for children who may not be returning to their parents’ care were not always well coordinated. There was no mechanism in place to ensure continuing coordinated support for children who needed this following de-registration from the CPR. 12 6. How good is operational management in protecting children and meeting their needs? Services and the Child Protection Committee (CPC) had produced a broad range of policies, procedures and strategies to guide staff in their work with children. The collation and use of management information was inconsistent across services. The impact of the Integrated Children’s Services Plan (ICSP) had not been fully evaluated. Staff had little awareness of the plan and how their work contributed to it. Services had sound systems to ensure safer recruitment of staff. Valuable training was available to staff. The support and management of staff holding child protection cases was variable across services. An imaginative approach to involving children in the development of policies was progressing well. Aspect Comments Policies and procedures Overall, policies and procedures were satisfactory. Individual services had appropriate and helpful child protection policies and guidelines in place. Staff across services also used as appropriate the CPC inter-agency child protection guidelines. These were now due for revision and updating. The CPC had produced a range of additional guidance and information to support integrated working. However, some guidance for staff lacked clarity, including guidance on information-sharing, and significant case reviews. There was no consistent approach to ensuring effective implementation of policies and procedures. The impact of policies and procedures on practice was not systematically evaluated. Operational planning Operational planning was satisfactory. The Fife Children’s Services Group had involved key partners in the development of the ICSP since 2005. The ICSP priorities for 2008-2009 were linked to the Fife Community Plan and the Single Outcome Agreement. Six local Children’s Services Groups developed local plans for children in line with these priorities. There had been regular progress reports on meeting the priorities set out in the 2005-2008 ICSP. However, there had been limited evaluation of the improvement in the lives of vulnerable children. The most recent local performance figures on protection of children were limited and did not focus on impact and outcomes. Staff working mainly with vulnerable children were not fully aware of the ICSP and its relevance for their work. The use of management information was inconsistent across services. There was no systematic approach to using performance management information to inform service improvement. 13 Aspect Comments Participation of children, their families and other relevant people in policy development Participation of children in policy development was good. The ‘Big Shout’ effectively brought together representatives from a range of forums, including Youth Forums, Scottish Youth Parliament, Young People’s Panel, and Pupil Councils. Participating children and young people came from a variety of different backgrounds. Staff were extremely supportive of the young people and a creative approach had established a strong foundation for meaningful participation of children. Children involved felt their views were taken very seriously. There had been limited success in seeking the views of families in their use of all children’s services. A robust and systematic approach to the participation of service users was yet to be fully established across all services. Recruitment and retention of staff Overall, the recruitment and retention of staff was satisfactory. Safe recruitment and vetting practices were now in place. These took account of relevant legislation and were supported by a range of appropriate policies. The recruitment of social workers had improved and there were few vacancies. The introduction of a senior practitioner grade had helped retain staff. However, senior practitioners and staff trained for joint investigative interviewing were unevenly spread across the area. The impact of health visitor vacancies was reduced by registered nurses supporting the service. Services were not working together to minimise the impact of vacancies and there was no joint workforce planning. Development of staff Development of staff was good. Services delivered well-planned single agency child protection training programmes. The CPC had developed an extensive range of multi-agency child protection training. A list and future diary of all training courses available was easily accessible on the CPC website. Training courses were systematically evaluated by participants at the time. The long term impact training had on practice had not yet been fully evaluated. Social work did not have a central database of training and development needs. Health staff with responsibility for child protection cases did not always have their work reviewed effectively. 14 7. How good is individual and collective leadership? Chief Officers and senior managers shared a vision to protect children. The Chief Officers Public Safety Group (COPS) scrutinised child protection carefully but did not provide sufficient strategic leadership and direction to the Child Protection Committee (CPC) or staff working to protect children. The vision of the CPC was clearly recognised by staff across services. The CPC had undertaken a wide range of activity but had not monitored the implementation or progress of agreed guidance and protocols. Chief Officers and senior managers were committed to the principles of joint working. Processes for quality assurance and self-evaluation had been recently introduced. The main points for action arising from audit and evaluation activities had not resulted in improvement plans. Vision, values and aims The quality of vision, values and aims was good. Collectively Chief Officers and senior managers adopted the comprehensive vision of the CPC to protect children. Most staff across services understood the collective vision to protect children and how it should direct their work with vulnerable children. Fife Council promoted diversity and supported the ‘Frae Fife’ project in significant work with young people from ethnic minority families. • The Chief Executive of the Council adopted the aims and values of the CPC and was committed to help keep children healthy, safe and living in their own communities. Senior managers across all council services promoted child protection as central to all work with children. Elected members had a very clear vision that every child should be supported to keep safe. • Within NHS Fife the Chief Executive and senior managers shared a vision to support child protection through services promoting the health, well being and safety of children. They understood their individual and joint accountability for all child protection work. Staff, including those not directly responsible for children’s services, were aware of their responsibilities to give appropriate priority to child protection. • The Chief Constable of Fife Constabulary had a strong personal vision to protect vulnerable people in the community, particularly children, and emphasised this to officers as core business of the force. The importance of child protection was further confirmed as integral to community safety as one of four pillars of Fife Policing Plan. Officers understood this expectation in undertaking their duties. Chief Officers understood well their collective responsibilities and accountability. Sound reporting arrangements to Chief Officers were in place. The CPC reported directly to the COPS group. A recently formed subgroup of Fife Partnership intended to involve members of the health board and council in scrutiny of public safety work. The Children’s Services Group (CSG) encouraged multi-agency working through the development of the ICSP. 15 Leadership and direction Collective leadership and direction was weak. The COPS group had a clear understanding of their collective responsibility to scrutinise child protection activity and the work of the CPC. The ability of COPS to ensure there was robust scrutiny of child protection work was hampered by insufficient performance and management information. The group did not give collective strategic direction for child protection services nor did it direct key priorities for child protection. Links between strategic planning for children’s services and child protection were informal and were often dependent on common membership of strategic groups. The CPC had restructured to improve focus and performance. A wide range of services were represented on the committee and helpfully included the Children’s Rights Officer to offer the perspective of children. The CPC had undertaken a range of activity, but this had not always resulted in intended changes or improvements in practice across services. Agreed short term tasks were supervised well to ensure they were completed. However, the CPC did not give sufficient direction to ensure agreed policies and protocols were implemented across services. The effectiveness of policies was not routinely considered. Guidance lacked clarity which led to confusion in practitioners and inconsistency of application. There had been delays in completing important developments such as a practitioners guide for working with children affected by parental substance misuse. Overall, Chief Officers gave priority to resourcing child protection and services shared some resources to protect children. The COPS group had given priority to funding the CPC and its support team and monies had doubled within four years. The support team had sufficient staff and budget for awareness raising activities and training. Several jointly supported posts were positive developments towards greater resource sharing. The CSG had begun to monitor spending to ensure the desired outcomes of the ICSP were met. Allocation of resources to child protection was not always prioritised jointly or linked to clear strategies to protect children. Leadership of people and partnerships Individual and collective leadership of people and partnerships was satisfactory. Chief Officers and senior managers worked together through the Fife Partnership, COPS group and CSG and promoted a partnership approach to services aimed at the protection of children. However, individual services continued to develop some policies in isolation from key partners. A collaborative ethos was not yet fully developed and services did not always consider a partnership approach. There were limited opportunities to learn from other partners’ expertise or benefit from combining tasks to avoid duplication. There were recent improvements in staff’s awareness of the need to work in partnership. Children and families benefited from some effective and well coordinated joint work across services. In education, Joint Action Teams and School Liaison Groups promoted joint working and ensured helpful multi-agency support was available for children. 16 Effective working relationships between social work, education and the Children’s Reporter resulted in a large number of looked after children, previously accommodated throughout the country, returning to live and be educated in Fife. Local groups in health, children’s services and child protection promoted partnership working between services. Children’s Reporters were often unable to take part in these multi-agency groups. Fife Domestic Abuse Partnership had initiated the helpful Children Experiencing Domestic Abuse Recovery group and the Domestic Abuse Unit. Partnership working with the voluntary sector was well developed. The sector was represented on Fife CPC. Voluntary services provided effective support and help to many children and their families. Funding for larger voluntary providers such as Children 1st was provided on a three-yearly basis promoting continuity of service. However, many voluntary services were locality based. There was limited considered planning in the commissioning and provision of services in partnership with the voluntary sector. Multi-agency screening of offence referrals to the Children’s Reporters had successfully reduced inappropriate referrals but implementation of this to non-offence referrals had been delayed. Leadership of change and improvement The leadership of change and improvement was weak. The CPC had promoted multi-agency self-evaluation and staff had a growing awareness of its importance in child protection practice. A series of ‘How Good is Your Practice?’ multi-agency seminars had raised staff awareness of self-evaluation. However, Chief Officers and senior managers across services did not give a strong enough lead on the importance of self-evaluation in building capacity for service improvement. The CPC had carried out a multi-agency case file audit which identified strengths and weaknesses. This worthwhile exercise had not been followed up with improvement actions on the areas identified as needing attention. Social work services had carried out useful audits of cases on the CPR. These had led to some improvements in service levels. For instance, the number and frequency of social worker contacts with families had improved. However, the audits had not yet focused on the actual quality of the service experienced, such as that of contacts, risk assessments and child care plans. There were no links between this audit work and the multi-agency case file audit carried out by the CPC. Council services did not have systematic approaches to self-evaluation of child protection in place. Single agency self-evaluation had not been given a high priority. Across partner agencies, including Fife Constabulary and NHS Fife, there was no systematic approach to single agency quality improvement. The CPC had made some use of joint inspection reports to benchmark performance but it was unclear what improvements had been made as a result. A recent case review had resulted in some confusion over procedures and the lessons learned from the process were not clear. There was a lack of consistent quality assurance by managers to ensure that poor and inconsistent practices were addressed and improvements made by individuals and teams. 17 8. How well are children and young people protected and their needs met? Summary Inspectors were not confident that every child needing help to keep them safe from abuse and neglect had been properly identified, assessed and protected. While there were examples of good practice and well developed services these were not yet consistent across the Fife Council area. Children who were clearly identified as being at serious risk of harm were often receiving the help and support they needed. In those cases their situation often improved as a result of the effective involvement of services. However, the response provided to concerns was variable and there were differences in the time taken to carry out an initial assessment of risk. As a result some children were left in situations of risk or without adequate support. Within the local authority area, inspectors recognised that services were improving but key developments such as multi-agency screening of children for whom there was concern, were not taken forward systematically. There was a need for leaders to give greater direction to the development of integrated planning and consistent partnership working to protect children. Individual services and the CPC had structures in place to identify and implement improvements in the protection of children in Fife. In doing so Chief Officers and the CPC should take account of the need to: • improve the participation of children and families in key child protection processes and ensure they are more fully involved in decision-making about their lives; • improve guidance on information-sharing, related support and training and improve consistency across services; • improve the processes to assess the risk and needs of individual vulnerable children and ensure assessments are sufficiently rigorous to identify the actions needed to protect children; • improve planning to meet children’s needs ensuring all children have sufficiently detailed plans which contain arrangements for monitoring and review; and • ensure that Chief Officers and senior managers direct and monitor the effectiveness of the CPC and key child protection processes. 18 9. What happens next? The Chief Officers have been asked to prepare an action plan indicating how they will address the main recommendations of this report, and to share that plan with stakeholders. Within four months Chief Officers should submit to HM Inspectors a report on the extent to which they have made progress in implementing the action plan. Within one year of the publication of the report HM Inspectors will re-visit the authority area to assess and report on progress made in meeting the recommendations. Joan Lafferty Inspector April 2009 19 Appendix 1 Quality indicators The following quality indicators have been used in the inspection process to evaluate the overall effectiveness of services to protect children and meet their needs. How effective is the help children get when they need it? Children are listened to, understood and Satisfactory respected Children benefit from strategies to Satisfactory minimise harm Children are helped by the actions taken Weak in immediate response to concerns Children’s needs are met Weak How well do services promote public awareness of child protection? Public awareness of the safety and Good protection of children How good is the delivery of key processes? Involving children and their families in Weak key processes Information-sharing and recording Weak Recognising and assessing risks and Weak needs Effectiveness of planning to meet needs Weak How good is operational management in protecting children and meeting their needs? Policies and procedures Satisfactory Operational planning Satisfactory Participation of children, families and Good other relevant people in policy development Recruitment and retention of staff Satisfactory Development of staff Good How good is individual and collective leadership? Vision, values and aims Good Leadership and direction Weak Leadership of people and partnerships Satisfactory Leadership of change and improvement Weak This report uses the following word scale to make clear the evaluations made by inspectors: Excellent Very good Good Satisfactory Weak Unsatisfactory 20 Outstanding, sector leading Major strengths Important strengths with areas for improvement Strengths just outweigh weaknesses Important weaknesses Major weaknesses Appendix 2 Examples of good practice The following good practice example demonstrated how services can work together effectively to improve the life chances of children and families at risk of abuse and neglect. Vulnerable in pregnancy project (VIP) Community midwives identified increasing numbers of babies displaying signs of withdrawal from maternal substance misuse. Many of the mothers had not been in contact previously with addiction services and their substance misuse was not known to staff during pregnancy. Child protection enquiries or assessment of risk did not take place until after the baby was born. VIP was developed from the drug liaison midwifery service in partnership with addiction and social work staff. Families for whom there was concern were identified at an early stage of pregnancy. Staff worked closely together to share information about vulnerable women. They assessed risks and needs of families. Staff planned well together and women had an individualised pregnancy plan to support them. Women and their families were supported intensively by specialist health staff, addiction nurses and social work staff from ante-natal registration until the baby was 12 weeks old. This support was extended for longer periods if required. Families had a named worker who met with them individually, got to know them well and coordinated support from other services. Women were helped to manage their substance abuse. They were supported to take advantage of effective post birth medical advice and screening. Support in parenting skills helped to improve the relationship between mothers and babies promoting better outcomes for children. 21 How can you contact us? If you would like an additional copy of this report Copies of this report have been sent to the Chief Executives of the local authority and Health Board, Chief Constable, Authority and Principal Reporter, Members of the Scottish Parliament, and other relevant individuals and agencies. Subject to availability, further copies may be obtained free of charge from HM Inspectorate of Education, First Floor, Denholm House, Almondvale Business Park, Almondvale Way, Livingston EH54 6GA or by telephoning 01506 600262. Copies are also available on our website www.hmie.gov.uk If you wish to comment about this inspection Should you wish to comment on any aspect of child protection inspections you should write in the first instance to Neil McKechnie, HMCI, Directorate 6: Services for Children at HM Inspectorate of Education, Denholm House, Almondvale Business Park, Almondvale Way, Livingston EH54 6GA. Our complaints procedure If you wish to comment about any of our inspections, contact us at HMIEenquiries@hmie.gsi.gov.uk or alternatively you should write to BMCT, HM Inspectorate of Education, Denholm House, Almondvale Business Park, Almondvale Way, Livingston EH54 6GA. If you are not satisfied with the action we have taken at the end of our complaints procedure, you can raise your complaint with the Scottish Public Services Ombudsman (SPSO). The SPSO is fully independent and has powers to investigate complaints about Government departments and agencies. You should write to the SPSO, Freepost EH641, Edinburgh, EH3 0BR. You can also telephone 0800 377 7330, fax 0800 377 7331 or e-mail: ask@spso.org.uk. More information about the Ombudsman’s office can be obtained from the website: www.spso.org.uk. Crown Copyright 2009 HM Inspectorate of Education This report may be reproduced in whole or in part, except for commercial purposes or in connection with a prospectus or advertisement, provided that the source and date thereof are stated. 22