2 STATE 1IVSITY COLWBIAN BLACK-TILr L

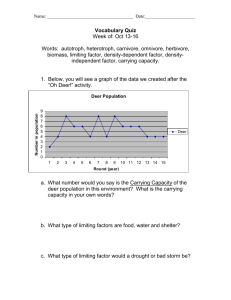

advertisement

OF T 0 1 iiCT 0135 .;VATI0N

JO1PAf:.ISji

TC1.NI.0 .:;S

COLWBIAN

01-

BLACK-TILr L

2

WILLIA

V'EST

'-2

i.

0

HINES

A TJi. IS

subiitted to

01 ...iGOi'

STATE 1IVSITY

in partial fulfillment of

the requirements for the

degree of'

'..

A

r'r'.

June 1961

JN

APPROV'D:

Redacted for privacy

Associjate Prol(essor of Fish and Uame Ivianagemen

In Charge of Major

Redacted for privacy

Head of Department of Fish and Game Management

Redacted for privacy

hairmaroJradu

ommi t tee

Redacted for privacy

Dean of Graduate Sohoo

Date thesis is presented______

Typed by Sylvia Anderson

ACKNOWLI.GiTS

Perhaps the r.ost important outcome of a student's

research is not in the results he obtains but rather in

the knowledge he gains while conducting his investigation. This knowledge is often imparted or stimulated

by those with whom the student has conferred. The

author is greatly indebted to the following individuals

and organizations for their generous assistance:

Arthur S. Elnarsen, Leader, L. Francis Schneider

and William C. Lightfoot, Assistant Leaders, Oregon

Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit, for the privilege

of conducting this investigation and for guidance,

field assistance, and manuscript reviewing.

Dajor Professor Lee W. Kuhn, Department of Fish and

Game Management for his ;uidance and thesis assistance.

Professors Foland . Iiniick, Department Head, and

Charles E. Warren, Department of Fish and Game Management

and Charlas E. Poulton arid Donald W. Hedrick, Departnent

of Range Management, Oregon State University, for their

advice on ways to improve this thesis.

Lyle D. Calvin, Agricultural Experiment Station

Statistician, for his advice on analytical procedures.

Francis F. Ives, Oregon State Game Commission

District Agent, for his field assistance and stimulating

attitude.

All graduate research assistants from the Oregon

Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit for their cooperation

throughout the study.

Mr. and Mrs. Fred Auer and Mr. and Mrs. Ross Dockins

of the Oregon State Board of Forestry for making living

conditions more pleasant while working in the field.

The Willamette Valley, Oregon Pulp and Paper, Pope

and Talbot, and the I. P. iller lumber companies and

the Oregon State Board of Forestry, the U.S. Forest

Service, and the Oregon State University School of

Forestry for granting permission to use their lands for

this study.

Foresters associated with these organizations were exceedingly cooperative in furnishing information.

OF ONTT

TAIL

I9OiUCTIUN .

.

.

.

,

.

wT}oLs AND f.oCTtmS.

Study Areas

.

1

..... .......

3

.

.

.

.

.

a

Sampleloutea .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

,

.

.

.

.

Observational Procedures

root Method . . . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

. ....... .

*

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

,

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

SpotlL::htMethod..........a..

SpotlightTests.

F- --SULTS

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

a

. a... .

10

.

a

. .... ...... is.

SpotlightMethod ..............

SpotlightTests.

Effects of leer Activity Changes upon

Counts . . .

.

.

.

.

.

.

,

Effects of Population Shifts and

Increases upon Counts , . . . . . .

Effects of Vegetation Changes upon

Counts

.

a

.

*

.

,

.

a

a

.

a

.

a

a

a

a

,

a

,

12

12

14

,

.

18

.

.

$0

38

'

Foot ethod . a .

a

.

a

a

'

a

a

Effects of Deer Activity Changes upon

Effects of Pooulation Shifts and

Increases upon Counts

.

.

.

.

.

Effects o Ve&;etation Changes upon

Counts .

a

.

.

a

a

,

3

4

8

6

9

.

.

a

a

.

.

.

.

.

39

41

*

44

46

,Ia.sas

Comparison of Spotlight and Foot

SamplingResults

SiY AWL Ci:CLUSiOS

BIBLAUO;.A?HY a

Ay.

,

,

.

,

a

a

a

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

a

a

a

.

a

a

.

.

.

.

a

,

a

a

.

.

.

.

47

50

5*7

LIST OF TABLS

1

2

Distribution an.d Description of Foot

and Spotlight Routes . . . . . a . .

7

a

Maximum Pistance

in Miles that

yeshine Could be

Observed by Various Spotlights .

Simu1td Deer

3

4

5

6

7

8

.

.

13

of the Maximum Distances

in Yards that Doer Antlers Could be

Recognized with Various Spotlights . .

.

15

A Summary of March through April, 1957,

Spotliht Counts from Three Routes in

the Adair and McDonald Areas a . a a a a

16

.

.

A

Results of Weekly Spotlight Counts

from Seventeen Routes between May and

September,l957 ............

17

Monthly Percentages of Classified

Deer Observed Bedded . . ' . a a

a

23

Comparison of Early and Late Deer Counts

Obtained from the Same Routes each

Night by Two Observers a a a a a a a

29

F.esulte of Weekly Foot Counts between

ay and September, 1957 a a a a a a a

40

LIST OF FIGU1 .S

Figure

I

2

Locations of seven study areas within

Benton nd Polk Counties, Oregon . . .

4

5

6

7

.

.

.

. .,,.....

24

Sums of movin average day and night

mean route counts for ten segments

ofthelunarmonth.,.........

26

A spotli;hted two-year-old doe which

was ear-taj:ed with "Scotchlite8

reflect1v eheettn to study nocturnal

moverents of black-tailed deer . . . .

.

31

Mean monthly deer counts for three

recently logged areas with southern

.

a

.

.

.

.

a

a

s

.

exposures

a

a

33

A comparison of monthly 4 p.m. mean

temperatures with the sums of the

monthly mean spotlight route counts

.

.

34

a

a

Monthly day and night percentage of

fawns in the total deer classified

byage

8

5

Monthly comoosition percentage of

mature male deer observed during the

dayandniht. .

3

.

a

a

a

a

.

.

.

a

a

a

A comparison of coefficients of

variation for eleven routes which wore

repeatedly sampled by the spotlight and

footniothods.....,..... ...

48

LIST OF APPENDICES

Appendix

A

B

Weekly schedule of spotlight and

foot route sampling from May 6 to

September2l,1957..........

57

Descriptions of seven lamps tested

.

.

.

on a spotlight range .

.

58

.

.

59

A summary of spotlighted deer sex

and age classifications obtained

between May and September, 157 .

.

.

61

Summary of ni.ht deer activity

observed while spotlighting between

.

.

.

May and September, 1957 .

.

.

62

$eptember,1957 ...........

63

A moving average analysis of lunar

effects upon night spotlight counts.

64

A summary of deer sex and age

classifications obtained from foot

routes between May and September, 1957

65

.

C

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

F

G

H

.

Eorizontal beam spread measurements

for seven lamps taken at twenty-five

yards.

D

.

.

*

.

Atmospheric conditions present while

spotlighting routes between May and

Atmospheric conditions present while

conducting weekly morning and evening

foot route counts between May and

September,l95?............

66

COi.:A I)N UT TO TI

i

C

II S 10

u

AI

'CT OBS:.t VATION

CULL BIA', BLACK-TATL'D

I:;i: IN wsTrN OF.GON

INTJ ULU CT ION

This investigation, under the auspices of the Oregon

Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit,1 concerns the study

of two direct observation techniques for enumerating

Columbian black-tailed deer, Odocoileus hemionus

columbianus (Richardson), in Benton and Polk counties of

Western Oregon.

The objectives of this work were:

(1) to compare the results of a daytime foot sampling

technique with a nighttime spotlight sampling technique

and (2) to study fluctuations in sampling results in

relation to deer habits and other possible influencing

factors.

Field investigations began March 1 and

terminated September 21, 1957.

Direct observation methods for obtaining big game

population trends are based on the assumption that

annual fluctuations in animal densities can be detected

by yearly changes in the number of individuals observed

by adequate sampling techniques.

The most suitable

technique for obtaining these observations would be one

1.

Oregon State Game Commission. United States Fish and

Wildlife Service, Wildlife Management Institute,

Agricultural Research Foundation, and Oregon State

University cooperating.

which, if used on the same population, gave the least

variation in animal numbers with repeated sempling.

A thorough understanding of deer habits is an essential

basis for developing inventory techniques.

The two

methods were tested under all prevailing weather

conditions to study deer habits and their influences

upon sarnoling results.

MbTLOLS AND ?vOOL.I. S

Study Areas

Preliminary sampling in the fall and winter of

1956 was conducted on the Adair Tract and in the

McDonald Forest of

enton County, Oregon.

Most of the

old growth timber was logged from these areas more than

30 years ago, and advanced stages of second-growth

timber are now found on most forest sites.

Recent

timber sales have been limited and selective cutting

units have been small.

Other areas, representing earlier stages of forest

succession were visited in April, 195?, to select

additional areas for testing the spotlight and foot

sampling techniques.

Consideration was given to the

following factors in judging the desirability of each

area:

(1) they should be heterogeneous in respect to

one another, but with each being typical of a Western

Oregon deer habitat; (2) vehicle access should be

possible by May; (3) the areas should be no more than

one and one-half hours traveling distance apart; and

(4) the areas should be subject to a minimum amount of

human activity.

Five additional areas were selected oil

the basis of this survey.

The locations of all areas

used throughout the spring and summer studies are shown

in Figure I.

Sample Toutes

All routes within an area had to be near one

another' to allow maximum time for sampling.

Each foot

route followed the same course that was spotlighted.

The maximum length of routes tested by both methods

could not exceed the distance that could be effectively

observed on foot during the four and one-half hours

following daylght.

Each week a total of 28 samples was obtained with

the two methods under investigation.

The weekly

sampling of eleven foot routes covered an observation

distance of approximately 35 miles, with the individual

transects varying from 1.0 to 5.5 miles in length.

Six

mornings and four evenings each week were spent sampling

on foot.

Only one route was walked during a morning or

evening period with the exception of the Skid Creek A

and B routes, whioh were 1.0 and 2.3 miles, respectively

(Appendix A).

These transects were observed on foot

each Friday evening, with Unit A being walked first.

The eleven foot routes were also sampled by the

spotlight method.

Starting in June, six additional

spotlight transects were also sampled.

This gave

weekly saiples for 17 spotlight routes that covered a

DORN P1<.

I

RILEY P1<.

N

MONMOUTHO

MONMOUTH P1<.

PEDEE

t

's__

LEGEND

PAVED ROADS

GRAVEL ROADS

o

.

ISI

23

TOWNS

PEAKS

-

CORVALLIS

COUNTY LINES

STUDY AREAS

PHILOMATH

TON

BE

VIA.

4MARYS

SCALE

1LLLA

lu 8 MILES

Lij

(I

'I

I

1

ALSEA

GREEN P1<.

- -

'

D%SO

BELLF0: TAIN

MONROE

FIGURE I.

LOCATION OF SEVEN STUDY AREAS WITHIN BENTON AND

POLK COUNTIES, OREGON.

distance of 65 miles.

The distribution and description

of each route is given in Table I.

The Green Peak A and B routes were alternately

spotlighted first each Sunday night (Appendix A).

This was done to compare the results of early and delayed

night sampling for the same routes.

Sootlihting along

the 15 remaining routes was kept consistent with respect

to time of night and day of week sampled.

Observational Procedures

Sampling began in the Green Peak area on May 6,

1957.

Foutes in this southernmost area were spotlighted

first each week.

Sampling progressed northward into

other areas as the week progressed.

The sampling proce-

dure involved moving into an area in the evening, spotlir2htin

its established transects that night, walking

its foot transects the next day, and moving on to the

next area where the procedure was repeated.

This weekly

circuit was continued for twenty weeks and terminated

September 21, 195?, one week before the opening of

Oregons general deer season.

Foot Method

Leer feed most actively during the early morning and

Table i:

Distribution and Description of Foot and Spotlight Routes

Hours to

Sample

Route

Lengths

Areas

Routes

Impaired

Visibility

bpotIi,bt

Foot

Spotlight

boot

Ày. Yards

Visible

Left Side

Green

Peak

Green Peak Unit A

Green Peak Unit B

*4.8

*4.8

2.4

2.4

1.3

1.3

2.5

2.0

14.5

9.3

Yew

Creek

Yew Creek Unit A

Yew Creek Unit 8

5.3

5.3

2.0

1.0

4.0

*2.8

132.7

41.7

McDonald

Forest

Soap Creek Burn

Oak Creek Drainage

4.3

5.4

4.3

2.5

1.7

4.0

65.7

Bald

Mountain

Bald Mt. Unit A

Bald Mt. Unit B

Bald Mt. Unit C

3.4

3.3

2.0

3.4

3.3

1.3

1.3

2.5

2.5

Skid Creek Unit A

Skid Creek Unit 8

Rickreail Loop Rd.

*1.6

1.0

2.3

5.5

wind

Creek

wind Creek Drain

Cedar Creek Burn

2.6

*4.6

2.6

Adair

Tract

Berry Cr. Trap Unit

Forest Peak

Soap Creek Pastures

2.2

6.8

2.6

2.2

64.3

34.7

Rickreall

Drainage

Totals

*

Routes approximately

return travel.

2.3

5.5

-

.5

.5

.7

1.0

2.5

1.9

4.0

1.0

2.0

3.0

1.0

3.0

2.0

82.9

86.3

59.3

46.5

29.0

-

14.1

124.5

.5

24.4

33.6

12.7

14.6

Grass

Ferns

Flevational

Changes

x

x

x

x

950-2690

975-1425

1700-2200

-

x

x

x

635-1675

200-1035

x

x

x

x

1000-1750

1000-2300

2610-3245

x

x

350-780

400-1650

400-1950

x

x

x

x

x

x

x

1000-2000

1150-1950

350-550

350-1700

250-275

29.1

length indicated, with counts being made on opposite side oi road while on

A

late evening.

The intensity and duration of mid-morning

and mid-afternoon feeding is variable.

Long transects

were established that required observations from about

5 a.rn. until approximately 9:30 a.m. to detect the

influences which irrsularit1es in mid-morning activity

have upon sampling results.

Sampling teriTinated earlier

in the morning on shorter routes.

Morning transect

lengths varied from 2.4 to 5.5 miles.

Evening sampling

was accomplished during the last two end one-half hours

before dusk.

Foutes varying from 1.0 to 3.4 miles in

length wore walked during this period.

Three of the eleven transects were always walked in

the evening, while another four were alternately sampled

morning and evening.

The remaining four transects were

consistently walked one morning each week throughout the

period of investigation.

The rate of foot travel along

transects varied according to cover density, topography,

and the number of doer observed.

The average walking

speed was 1.2 miles per hour.

Transects were always started from the same point

and walked in the same direction.

A pair of 6 x 30

binoculars was used to search distant terrain and shadow

areas.

All terrain along each side of the route was

scanned in a systematic manner starting at the ridge tops

and working downhill.

Transect boundaries were established along natural

terrain features in situations where routes followed high

ridges and the view was riot restricted by adjacent ridge

This restriction was necessary because in areas of

tops.

unlimited viewing, adequate searches could not be made

of all deer habitat.

Spotlight Method

All spotlighting was conducted from a jeep that was

usually driven in second gear, low range, four-wheel

drive.

The average sootlighting speed was between three

and four miles per hour.

A model 740 Unity, 95,000 candle power sotlight with

a number 4535 General Electric lamp was used throughout

the study.

This lamp produces a horizontal and vertical

beam spread of five and one-half degrees and four degrees,

resoectively.

The lamp filament is covered by a hemi-

spherical mirror which directs all light back to the reflector before it is projected.

This feature provides a

well defined beam with little evidence of side light.

A systematic search for deer was made in all habitat

on the left side of the vehicle.

Thus, the maximum

sDotlight transect width was equal to the effective

distance of the light beam.

The spotlight was continually

operated with a horizontal, short stroke, whiing motion

as a search was made up and down the slopes from the

left vehicle headliht to the taillight.

The same

searching procedures wore used as the spotlight beam

was returned to the front of the vehicle.

1his continuous

searching provided a minimum of double coverage of

habitat at the slow speeds traveled.

The vehicle Was

stopped when a deer or animal eyeshine was Seen.

Leer

sex, age, and activity were classified by using $ x 30

binoculars.

Spotlight Tests

A spotlight range was established to determine the

suitability of several lights (Appendix B) for counting

deer and to test assumptions concerning the observer's

ability to see and classify deer during different times

of the lunar month.

Circular, convex "lAW Cataphote" highway reflectors,

five-eighths inch in diameter, were mounted in pairs to

simulate deer eyes when sootlighted.

These simulated eyes

were placed three feet above the ground and separated by

one-tenth mile intervals along a one-mile strip.

Additional reflectors were backed by deer antlers to

give the effect of nature male deer.

These were placed

at 50 yard intervals along a Z0O yard line extending

from the spotlight.

The horizontal beam spread intensity of each light

was measured at 25 yards from the light.

Foot candle

measurements were taken with a Weston, Model 756 street

light meter at one foot intervals along a plane at right

angles to the light beam.

RESULTS

Spotlight Tests

Table 2 shows the maximum distances which simu1ate

deer eyeshine could be observed by seven different

spotlights during full and no moon conditions.

Lamps

1484 and 4516 were inferior because they could not

produce observable reflection at distances equal to the

other lamps tested.

Measurements of beam spread

intensities (Appendix C) showed that these two lamps did

not project a narrow beam of concentrated light.

A

concave mirror in front of the lamp element in lamps

4435, 4535, and 4522 projected all light back to the

reflector before it was projected in a narrow beam.

These lamps produced highest candle power readings

at 25 yards (Appendix C).

Lamp 4522 was designed as

an aircraft landing light and is not suitable for deer

spotlighting because of its high wattage requirements,

short life expectancy, and intense heat production.

Table 2 indicates that the two extremes of no

moon and full moon bad no effect upon the distance which

simulated deer eyeshine could be seen with the naked eye

or optical equipment.

Wall (48) states, "I fee]. quite sure that your

counting more deer under Lull-moon than under no-moon

13

Table 2

Maximum Distances in Miles that Simulated Deer

Eyeshine Could be Observed by Various Spotlights

No Moon

Full Moø

No.

*Distance

in Ft. to

500 c.p.

1+1+35

lk.9

Light

Naked

lye

l3inoc.

30x

Scope

.5

*9

.9

i.9

.5

.9

12.5

.5

.9.

11.9

5

10.9

.5

6.6

6.0

Naked

Eye

7 x 50

Binoc.

30x

Scope

.5

.9

.9

.9

.6

.9

.9

.9

.5

.9

.9

.9

.5

.7

.8

.7

.9

.5

.7

.9

.1+

.7

.8

.5

.8

.8

.1+

.7

.7

.1+

.7

.8

7 x 50

v.12-16

1+535

v.6

1+522

v.13

v.12..l6

1+515

v.6-8

11+81+

v.6-8

1+516

v.6

Distance in feet from light to 500 candle power.

conditions indicates truly greater acttvity of the deer

themselves.

Theoretically, if moonli:.ht were to have

any significant effect upon the visibility of eyeshine

it should interfere, since it would decrease the

intensity-difference between the glowing eye and its

surrounding.

Since your data go in the opposite

direction, I am sure that no human.visual factor is

involved."

A comparison of the maximum distance which mature

deer antlers could be recognized during full and nomoonlight conditions is given in Table 3.

Moonlight did

not influence the observer's ability to see antlers.

Lamps 4405, 1484, and 4516 appeared to be the least

suited for classifyini doer features because of their

wide beam spreads (Appendix C).

From these data, the

assumption was made that the presence or absence of

moonlight had no effect on the observer's ability to

classify deer sex, age, or activity.

Spotlight Method

A total of 4254 deer were seen while completing

1342 miles of spotlight sampling between March and

September, 1957.

Tables 4 and 5 show the results

f

these night counts while Appendix D gives the sex and

age composition of doer classified between May and

Table 3

A Comparison of Maximum Distances in Yards that

Deer Antlers Could be Recognized with Various Spotli.hts*

Full Moon.

Light

No.

7 x 50

1inoc.

30x

Scope

Naked

Eye

No Moon

7 x 50

inoc.

30x

Scope

141+35

100

200

200

100

200

200

14535

100

00

200

100

150

200

14522

100

250

200

100

200

200

1+515

100

200

200

100

200

200

50

200

200

100

200

200

50

200

200

50

150

200

50

150

150

50

150

150

14516

*

Naked

ye

Simulated deer eyes were backed by deer antlers and placed at 50

yard intervals.

16

Table k

ri1, 1957 Sot1i;ht

A Summary of March through

Counts from Three outos in the Adair and McDonald Areas

Oak Creek Drainag

Date

Soap Creek Burn

Forest Peak

Date

Counts.

Counts

Date

Counts

3/1

13

3/26

'+3

3/2

23

3/9

8

k/k

'+5

3/12

20

/li

8

k/6

3/19

12

3/1k

17

k/il

27

'+/2

11

3/21

25

k/18

53

k/il

25

3/22

8

14/19

5k

'+/i5

1k

3/28

10

14/23

17*

'+/i7

7

17

'+/25

60

14/22

19

k/8

16

k/29

k/27

19

4/13

1k

k/17

20

k/2

1k

'4/28

10

Total Deer

180

Observations taken during fog

386

weather,

150

Tah3e 5

eek1 y Spotlight ounta frcm Seventeen

Routes betreen May and September, 1957

fle;iüt; of

pot1ight_Routes

weeks

1

2

5

6

7

3910

Green1eakUnitA

GreenPeakUnitB

6io8ki533

911

7191015

Ye.iCreekUnitA

252710111220101211

Yew Creek Unit B

Soaj Creek Buru

2k 20

44 44 32 20 2k 24 18 8

0akGreekDrairage

B1d Mt Unit A

8

17*125

*

-

Fogged in sample

84129

8 11 10 14

1

7

13 15 11

5 9

63 54 26 30 28 37 29 18 1

21 14 19 16 15 12 10 10 7

18 25 22 14 8

6 9 6 13 8

3 4 5 11 11

3 9 6 11 13

a' co

'.O

r4

r4

a'

Total deer

7

*

____3'J

1

31538935k?

4

15

23

31

6

9

5

12

23

2

5

2

*

2

21?

9

1k

20

22

1k

33

23

29

11010

10

693

7

5

1717

16

1k

23

27

13

6

23

3.8

812

14

7

23

9

6

8

7

7

9

27

3

12

6

5

11

7

23

10

8

4

6

30

11

14

6

10

ii

9

28

7

12

14

5

10

5

r4

L(\

0'

r-

co

t

r4

9

17

1

4

4

913

13

16

18

16

911

173

289

259

453

150

138

8

41104235414458976012

10816014331632

2325754

6552242302k82213480

10 12 16

BaldMt.UnitB

BaldMt.UnitC

SkidCreekUnitA

Skid Creek Unit B

Rickreall Mt. Loop

wind Creek Drainage

Cedar Creek Burn

Berry Creek Trapping

Forest leak

Soa Cr. Pastures

*

7

iJ

r-4

r-4

4

r4

.D

u'

a'

,4

r4

0' 0'

o 'o

r4

r4

7

33

10

17

1

14

10

7

21

7

14

4

5

6

6

5

15

7

7

19

6

8

4

1k

34

13

13

4

13

5

t'\

4

17

3

5

9

8

16

5

-

0'

C\

0

('J

r4

r4

r-4

r4

r4

ir

13

35

5

9

4

10

5

0

0

t'.

"\1

r-4

co

r4

*

*

27

8

8

3

4

6

$

Lf\

r4

1k1

594

211

227

92

112

121

September.

Appendix E describes the activity of deer

that could be classified.

The assumption was made that

the sex and age compositIon and the activity of all deer

not classified was similar to the classified results

obtained during all months.

A further assumption was

made that changes in deer activity from the bedded to

standing position would Influence count results.

Thore

fore, changes in the percentage of bedded deer were used

as one criterion for studying nocturnal deer activity.

Effects of Deer ActIvity Changes upon Counts

This study was not designed to evaluate the difficult

problem of factor Interaction.

Single factor reasoning

was used to interpret changes In deer activity.

This

approach to understanding biological phenomena is often

dangerous and misleading.

Changes in daily weather,

seasonal weather, and lunar phase were recognized as

factors which could influence deer activity and thereby

affect sampling results.

Veather conditions were variable during the spring

and summer months of l97.

Foggy and low-ceiling

cloudy weather were common until the middle of July.

Frequently these conditions did not extend into all

study areas.

Appendix F smmarizes by routes, these

conditions as they existed during spotlight sampling.

The percentage of bedded deer was computed from

counts made under clear versus cloudy skies to determine

If this atmospheric difference had a possible effect upon

night activity. All route counts for cloudy and mostly

cloudy weather were combined and conpared with a

systematically selected number of samole counts represeritthg clear and scattered cloud conditions. The

criteria used for determining cloud cover are given in

Appendix F. This comparison revealed that bedded deer

constituted 21 and 18 per cent of the classified deer

for cloudy and clear weather, respectively. Thus, no

importance could be attached to the influence of cloud

conditions upon night activity.

Between March and

September,

twenty-one samples

were taken in the rain. The intensity of precipitation

varied from heavy rain downpours to moderate "fog drip."

The Oregon State University weather station reported that

9.4 inches of precipitation fell during March and April

with 26 days contributIng .10 of an Inch or more

(13, p. 39; and 14, p. 57). During seven nights In this

period, rain was encountered while making night

observations. Late spring and early sunmer precipi-

tation was less, with most of it falling In the fori

of light to moderate rain or heavy "fo drip."

Early spring counts revealed that 80

per cent of

the deer were active during rainy nights.

This figure

approximates the peroentaze which was active for all

weather conditions during the summer months (Appendix

E).

Thus it seemed that rain did not retard early

spring night activity.

Perhaps this was due to the

deer being conditioned by the regularity of rain

throughout the winter months.

Late spring and summer

precipitation was so infrequent that its effects upon

night activity could not be evaluated.

Vtthen a route or a portion of it was tfogged_in,fl

deer counts were not comparable to those obtained when

visibility was not restricted.

Under foggy conditions,

the spotlight beam penetration was sometimes greatly

restricted.

"Fogged-in" counts were made only for the

purpose of studying doer activity.

These counts were

not included in the comparison of the two census methods

results.

Foggy weather conditions, with an absence of wind,

did not seem to retard deer activity.

Only 16 per cent

of the deer were bedded under such conditions.

However,

some 35 per cent were bedded during foggy and windy

weather.

This aug.

eta that wind may influence deer

activity.

The three categories of "no wind," "breezy," and

"windy" weather were used to study the effects which wind

21

velocity was

highly variable at different points along each route.

seemed to have upon deer activity.

A subjective estimate was

!nade of

wind

the average air turbu-

lence for each route sampled by classifying it into one

of the three categories.

The sums of mean route counts for the "no wind,"

"breezy," and "windy" categories were 132, 108, arid 9?,

respectively. These results were obtained from the

samplings of ten routes that were spotlighted between

The Student's "t" test indicated

that a significant difference, at the five per cent

level, existed between the results of the "no wind" and

May and September.

"windy" counts.

Deer apparently preferred the leeward slopes during

windy weather. This was particularly noticeable during

the first part of the study when winds tended to

accentuate lower temperatures. A leeward preference was

less noticeable during the late summer months when night

temperatures were warmer.

No correlation existed between the percentage of

bedded deer and the air temperature recorded at the

beginning of each sample. This comparison was complicated

by frequent, large temperature differences encountered

during the sampling of routes on which there were large

changes in elevation, Table I.

The weather was cool, and cloudy with considerable

precipitation in W;arch.

A higher frequency of clear

warm days occurred as spring progressed into suner.

The average daily maximum temperature increased to

about BC degrees Pahrenheit by September.

Even though

the maximum temperature increased greetly, the average

monthly minimum temperature did not increase more than

10 degrees Fahrenheit.

These increased daytime and

relatively stable nighttime temperatures suggested

that a seasonal day to night change in feeding

activity might affect the results of night counts.

Small differences existed between the monthly

percentages of bedded deer, Table 6.

Normal variation

or better springtime ground visibility nay have been

realonsible for the slightly higher percentages

observed during the spring months.

No changes in

seasonal night activity could be detected through a

comoarison of monthly fluctuations in bedded mature

and yearling deer number.

Here, the assumption was

made that the seasonal activity habits of all sex and

age classes, exclusive of fawns, were the same.

Mature male deer were observed to change their daily

activities as the suriirner progressed.

Increases in night

observations of bucks occurred in the late summer while

at the same time fewer bucks were seen during daytime

This suested that nocturnal

sampling, Figure 2.

buck activity was greatest during the late summer

months.

Dasmarn (2, p. 145) in his studies of b1aek

tailed deer in California, states that, 'Durthg late

July and early August bucks are less evident.'1

Ha

continues by saying that the older msles move into

heavy cover about the time their antler velvet begins

to shed.

It was difficult to classify yearling deer by sex

and age at night.

Sex identifIcation was hindered by

the fact that eyeshine tended to obscure small antlers

when they were present.

On the Adair Tract and

Mconald Forest either-sex hunting area, Hines (6, p. 7)

found that fully developed yearling antlers varied from

one to nine inches in length,.

It was thus impossible

to classify enough yearlin.s to study their nocturnal

habits as a group.

A lunar month may be defined as the period from

new moon to new moon,

According to Jones (7, p. 76)

its mean length is approximately 29.5 days while the

actual length nay vary considerably from the mean

value.

The name, lunar phases, is cormected with the

variations in the

visible outline.

Waxing and

waning refer to respective increases and decreases in

the visible outline which occur before and after a full

Table 6

Monthly percentages of Clas.ified Deer

Obaerved i3edded

Months

No. Standing

No. Bedded

Per Cent

*

March and

April

May

June

July

371

221

268

23

300

223

78

61

52

58

91

k7

21.1

21.6

16.3

19.3

23.5

1?.k

5xc1sjve 0t fawns

August

September

24

35

30

25

w

4

I-

2O

0

Lu

'5

5

I]

JUNE

JULY

AUG.

SEPT.

MONTHS

FIGURE

2.

MONTHLY

COMPOSITION PERCENTAGE OF

MATURE MALE DEER OBSERVED DURING THE DAY AND

NIGHT (EXCLUSIVE OF FAWN OBSERVATIONS).

25

moon, respectively.

There is a conimon belief that deer restrict their

diurnal activity during the middle of lunar month when

night illumination is the greatest.

It is contended

that moonlight either stimulates or allows prolonged

nocturnal activity to occur, and this results in less

diurnal activity.

All spotlight results were classified into ten,

three-day segments of the lunar month.

Analysis of

variance was used to determine if differences existed

in the results of these ten phases, which showed higher

counts during the second and third quarters of the

lunar cycle (8, p. 227).

A significant difference,

at the five per cent level, existed between these

results, which were weighted for this test.

Analysts

of variance also indicated that there was a difference,

at the five per cent level, between the number of

standing and bedded deer observed in the above ten

lunar month segments.

A moving average analysis was also used to comare

the sampling results obtained under different phases of

the moon.

Appenix G presents the computations for

this analysis, while Figure 3 presents these results

graphically.

This analysis supports the conclusions

of the previous tests.

Leer seemed to be most active

LUNAR SEGMENTS

1-15

4-lB

7-21

10-24

13-27

16-30

19-3

22-6

25-9

28-12

19

18

U)

I

z

D 17

0

C)

LU

f- is

0

z

LU

Li..

0

14

U)

U)

12

IC,-

FIGURE 3. SUMS OF MOVING AVERAGE DAY AND NIGHT MEAN ROUTE COUNTS FOR TEN

SEGMENTS OF THE LUNAR MONTH.

at night during the middle of the lunar month, when

illwination was the greatest.

This accelerated

activity aoeared to cause siynificant increases in

spotlight counts,

Many investigators recognize nocturnal movements

as part of a deer's daily cycle, but they rarely

discuss them in relation to moon ohases (12, p. 149,

558; 4, n.

9, and 5, p

213).

Linsdale, however,

found that moonlight did not regulate nor was it

essential to foraging and other movements of blacktailed deer (9, p. 122).

In Finland, Slivonen

(11, p. 20) found that, "Preliminary control experi

ments suggest the probability of a stimulating effect

of moonlight upon the nightly activity of animals."

Changes in deer activity during the night could

effect the results of repeated route counts

accomnlished at different hours.

Counts in brushy areas

would be most influenced by such changes since bedded

deer would be more difficult to deteot than standing

animals.

A time difference existed between the sampling of

the first and last route each night.

The Fiokreall

route was completed the latest, with observations

terminating about 2 a.m.

Totals of about 1500 deer were observed during

the seven earliest and seven latest samples taken each

week. Bedded deer comprised 22.4 per cent of the

earliest and l.4 per cent of the latest counts. Thus,

no appreciable change in deer activity was detected

before the predawn hours.

In the late summer, a second observer was used to

spotlight the same routes a second time each night.

These predawn counts were about one-thrd lower,

Table 7, with 55 per cent of all classified deer

bedded.

Bedded deer constituted only 25 per cent of

all deer classified during the first nightly counts.

This suggested that a retardation of predawn activity

did occur and that this decrease in activity tended to

reduce the number of deer seen.

In support of this theory, Linadale (9, p. 268)

reports that there may be no black-tailed deer activity

in the open between midnight and daylight. Halloran

found that white-tailed deer commonly feed at all

times of night during the late summer. Taylor

(12, p. 150) cites Fuff (10, p. 26) as saying that

white-tailed deer, Odocoileus virginianus vlrginianus

(Zimmerman), have been known to feed until near midnight.

He continues by saying that some individuals are active

a greater part of the night but that there appears to

be a period of night inactivity just as in the daytime.

Table 7

A Comarison of Early and Late Deer Counta Obtained

from the Same Routes Each Night by Different Observers

Spotlight Routes

Cedar Creek burn

md Creek Drainage

Rickreall Mt. Loop

Bald Mt. Unit C

Nald Mt. Unit B

Bald Mt. Unit A

18th Ueek

Early

Late

8

8

27

1

0

8

6

16

13

0

3

0

Oak Creek Draina;;e

Soap Creek Burn

Yew Creek Unit B

Yew Creek Unit A

Green Peak Unit 3

Green Peak Unit A

Total Deer

-

Fogged in

19thJoek

Late

Early

Late

1k

11

30

3

12

13

5

12

7

k

6

21

1

7

9

2

23

18

13

5

7

52

38

2OUi..:eek

Early

1k1

0

3

6

2k

28

k

2

7

11

16

0

3

5

3

25

6

18

16

12

11

12

7

5

13

6

5

6

113

l4O

88

30

ffects of Population Shifts and Increases upon Counts

Population shifts acpeared to be one of the most

important factors causing fluctuations in weekly counts.

Here, population shifts describe movements of animals

into and out of open areas whore changes in their numbers

could readily be recognized.

In general, the home range of black-tailed deer

was observed to be small In size.

contained numerous

Instances

Daytime sight records

where the same Individuals

or groups were repeatedly seen within restricted areas,

oftentimes no larger than five acres In size.

In the winter of 1956-5?, several deer, along the

Berry Creek route, were live-trapped and ear-tagged with

circular aluminum tags covered with 'Seotohlite1'

reflective sheeting, }lgure 4.

Night observations of

these tagged deer suggested that their home range was

small during the summer months.

The greatest observed

movement occurred when two individuals shifted their

activities about 400 yards from a rapidly drying forb

and grass opening to a small area containing volunteer

legumes and remnant fruit trees.

A frequency distribution of all sight records for

each route, by one-tenth mile Intervals, revealed that

the most important population shifts affecting route

71

FIGURE 4.

A SPOTLIGHTED TWO-YEAR-OLD DOE WHICH WAS EAR-

TAGGED WITH "SCOTCHLITE" REFLECTIVE S}ETING TO STUDY

NOCTURNAL MOVEIVENTS OF BLACK-TAILED DEER.

counts occurred from relatively open south slope areas.

Leer were concentrated in these areas during the spring

when warmer temperatures and a greater abundance of forb

and grass forage were present.

Frequency distribution

data indicated that population dispersals occurred from

these areas during June and early July.

Figure 5 shows

the mean monthly sotlight counts for three such areas.

Perhaps earlier maturin

vegetation and higher

temperatures on south slopes influenced population

shifts from these areas.

The mean monthly 4 p.m. temperatures were plotted

and compared with the sums of mean monthly route counts

to further study the effects which temperatures had

upon total counts.

These temperature data were recorded

at the Oregon State University Hyslop Agronomy Farm in

the \Nillamette Valley.

given in Figure 6.

A comparison of these data is

It can be seen that an inverse

relationship exists between late afternoon, or near

maximum temperatures, and the sums of mean monthly deer

counts.

Care should be taken not to interpret Figure 6 as

meaning that there were fluctuations in night activity

which were caused by temperature differences and

resulted in higher or lower counts.

The suggested

implication is that temperature fluctuations wore in

25

2

0

0

a:

15

LiJ

0

>-J

I

2

0

2

I0

w

[.J

APR. 30 MAY 31

JUNE30 JULY 31

AUG. 31

SEPT.21

MONTHS

FIGURE 5.

MEAN MONTHLY DEER COUNTS FOR THREE

RECENTLY LOGGED AREAS WITH SOUTHERN EXPOSURE

SLOPES.

COUNTS.

ROUTE

SPOTLIGHT

MEAN

MONTHLY

THE

OF

SUMS

THE

WITH

P.M.

4

MONTHLY

OF

COMPARISON

A

MEAN

TEMPERATURES

6.

FIGURE

MONTHS

21

SEPT.

31

AUG.

31

JULY

30

JUNE

65

70

Z

75

w

80

cZ

85

165

°'

170

¶2

'75

Iw

180

85

some way related to population shifts which caused

seasonal differences in route counts.

Significant increases in deer numbers occurred in

the late spring with the 1957 fawning season.

It was

necessary to study the Influences which this population

increase had upon night counts.

Total monthly fawn

counts and classified fawn actiTity data were used as

indices for determining nocturnal fawn behavior and its

effects UDon total counts.

The first new-born fawn was seen in the Wind Creek

drainage on the morning of May 25, 195?.

It was believed

that the fawning season peak occurred during the first

week of June.

This was based on the observed decline in

frequency of does with distended flanks.

The last

pregnant doe was seen along the Oak Creek route on

July 30, 1957.

Her genital region was enlarged, suggesting

that her fawning time was near.

Spotlighted fawns were usually observed bedded

during the first weeks after the peak of the fawning

season.

During June, only in four instances was a doe

not in the near vicinity of each fawn seen.

In July,

mature does were more frequently observed feeding alone

or with groups of deer that contained no fawns.

The

fawns were usually seen by themselves, either bedded or

stand thg.

In early August the night doe-rawn relationship was

similar to that of July.

The does, fawns, and frequently

yearlings, ciere united into distinct family groups during

late August and 5eptember.

The percentage of fawns, from all deer classified

each month, was used as an index to study night fawn

activity.

It will be seen that the percentage of fawns

remained stable until September, suggesting that night

fawn activity, Figure 7, dId not accelerate until late

summer.

Here, the assumption is made that significant

increases in fawn movements, from the bedded to standing

position, would be reflected by the proportion of fawns

seen in all deer classified by age.

The observed increaso in night activity of fawns and

mature bucks did not cause increases in weekly counts.

Average weekly counts for three week intervals, during

the last twelve weeks sampled, ranged between 163 and

170 deer.

Here a ratio estimate technique was used to

predict three missing sample values by utilizing all

results obtained by both methods.

Population shifts,

deer dispersals, and vegetation growth tended to reduce

sampling results as the summer progressed.

These changes

prevented late summer counts from being higher than

spring counts, even though the fawn additions increased

the population.

35

30

U,

z

Ui

0

25

20

z

Ui

C-)

Ui

5

JUNE

JULY

AUG.

SEPT.

MONTHS

FIGURE

7.

MONTHLY DAY AND NIGHT PERCENTAGE OF

FAWNS IN THE TOTAL DEER CLASSIFIED BY AGE.

Iffects of Vegetation Changes upon Counts

Early spring deciduous shrub and tree growth

hindered the spotlighting of some slopes that were highly

visible during the winter.

Leaf growth on species such

as vine maple Acer oircinatum Pursh.,1 big leaf meple

Acer macrophyllurn Pursh., ocean spray Holodiscus

discolor Pursh., thimbleberry Rubus parviflorus Nutt.,

sairnonberry Bubus spectabilis Pursh., hazel Corylus

californica Pose, Oregon alder Alnu

oregona Nutt.,

and Oregon oak Quercus garryana Dougl. began to conceal

the presence of deer and their activities.

This growth

became evident in mid-April at low and medium elevations.

It was well developed by the end of May.

At higher

elevations, spring growth was about two weeks later in

gaining its full complement.

Further restrictions in visibility came when

herbaceous vegetation reached several feet in height.

This followed the initial deciduous shrub and tree

growth.

Bracken fern, Pteridium a4uilinum pubescens

Underw., was the most abundant species.

it grew to a height of six feet.

In places,

At medium and low

elevations fronds of this fern opened during May, while

1.

6

Abrams's (1955) Illustrated Flora

acifie

States was used to identify all plant species.

on the higher slopes this development was not reached

merata L.

until June. Tall grasses such as Lactylis

and Jlus laucus Bucki. also started to conceal the

presence of deer in open areas by late May.

Growth of herbaceous roadside vegetation progressively restricted the distance which could be spotlighted as the summer progressed. Table 1 shows those

routes which contained considerable amounts of this

interfering vegetation.

Deer counts took an appreciable drop In May as may

be noted by conmaring the early spring counts given In

Table 4 with the same route counts given In Table 5.

This suggests that in May vegetation growth was one

factor contributing to the decline in sampling results.

Foot Method

A total of 2198 deer was seen during approximately

650 miles of daytime foot sampling. Table 8 gives these

observations for May through September. Approximately 35

per cent of all deer wore not classified by sex and age

(Appendix H). This was due to insufficient observation

time, poor light conditions, or inadequate optical

equipment.

Table 8

Results of Weekly Foot Counts betweeu

May and September, 1957

Foot Routes

Green Peak Unit A

GreenPoakUnitB

Yew Creek Unit A

Soap Greek Burn

BaldMt.UnitA

Ba1dMt.UnitB

SkidCreekUnitA

SkidCreekUnitB

Rickreall Mt. Loop

Wind Creek Drainage

Berry Creek Trap Unit

Weeks

May

2 3

*

-

Unsampled

Fogged in sample

July

10 11

4

Seternber

August

1k 15 16

18

19

20

0321*7221365k 1721k

*

k

19

17

2

8

3.

k

0

5

7

7

2

20

7

6

1

*

+6

5

3

5

6

12 5 13

* 29

*

8

0

9

12

13

17

6

1

8

3

k

5

3

7

10

6

9 12

17 27

12

21

3k

13

57

10

56

0

29

16

3k

21

29

39

27

2k

kl

8677611537

562k* 592].812

2k

235690

24O

5k3

1k175

9221k 92

kl3lk 701997 6119

713

12032735621000k

61k983 532 61k ilk 32283

6

58 12 23 1k 22 65 30 22 *

20 7 7 1k 17 7 15 17

0 2 * 5 2

o co

Total deer

June

6 7

C

-

Lf\ 0

r-4

Co

Co

'O

t- tU\ tr-t

\

0'

(7

t-

50

8

+3

37

13

0

3.

1k

6

0

\O

$

r-4

k9

9

1

$

r4

1t\

U'

C'

v-4

rl

*

9

19

6

8

0'

0'

2

8

12

3

5

*

P\

CO

CO

C-

0

0

tf\

U'\

i-4

-I

I

5k5

269

38

1k

0

0

kO

16

22

50

3k

k

29

16

3

k

Co

Lt\

0'

Effects of Leer Activiy Changes upon Counts

Cloudy weather conditions were more common during

daylight observations (Appendix I) than they were during

night sampling (Appendix F).

Most of this cloudy weather

occurred during the first half of the 20-week sampling

period.

This weather caused subdued light which lessened

the contrast between the deer pelage and the surrounding

vegetation.

Deer were more difficult to detect under

these poor light conditions.

Sample counts could not be

used to interpret activity changes in relation to the

presence or absence of clouds because of this varying

visibility of doer.

Leer seemed to forage later into the morning on

cloudy, cool days.

Five times as many deer were seen

along the last two miles of the three longest routes,

Table 1, during the first l

weeks of sampling as

were seen during the last seven weeks.

Deer had

presumably bedded, and were less conspicuous, before

sampling was comleted on the warm days of August and

September,

Deer usually did not start feeding in sunny areas

until near sunset on hot days when the 5 p.m. temperature was near the daily maximum.

foragin

On these evenings,

deer were first observed on shady slopes.

42

Foraging activities commenced earlier in the afternoon

on all slopes when the days were cloudy and cool.

"Windy" weather occurred during 10 per cent of the

197 daytime route samplings, and it occurred equally

on clear and cloudy days.

"No wind" and "breezy" Wind

conditions also occurred equally duiin: clear and cloudy

route samplings.

Sums of moan route counts for the

"no wind," "breezy," and "Windy" categories were 41, 32,

and 27 deer, respectively.

These Liè:ures were obtained

from the sampling results of five routes which were well

represented in all tbree categories.

The sums of the

mean route counts for all 11 routes were 78 and 65 deer

for the "no wind" and "breezy" conditions, respectively.

The Student's "t" test did not indicate a difference

between these data at the Live per cent significance

level.

Insufficient observations durIng windy weather

prevented a comparison of the "no wth&' and "windy"

results for all routes.

Both Dasmann (3, p. 82) and Linadale (9, p. 316)

observed that wind caused black-tailed deer to seek

sheltered spots while Aldous (1, p. 328) stated that

deer seek the protection of heavy cover during 8trong

winds.

Heavy rains occurred on only one occasion during all

foot sampling.

The total deer seen on this evening sample

of the Bald Lountain Unit A route was within the range of

previous counts.

It was not oossible to evaluate the

effects which rain bad upon diurnal activity since the

duration and intensity of precipitation was highly

variable.

Poor light conditions and wet optical equip-

ment lessened the ability to detect deer under these

conditions.

Mature male deer were the only sex and age group,

excepting fawns, observed to change their daily pattern

of activity as the summer progressed.

Figure 2 depicts

the nionthly percentage of mature bucks seen in the

total mature deer classified by sex and ago each month.

There was an appreciable drop in the proportion of buck8

seen during the August and September daytime counts.

Corresponding increases in night observations of mature

bucks occurred during the last two months of investigation.

It is commonly believed that morning deer activity

is retarded following nights of full or near full moon

conditions.

The daytime counts were teatd by a moving

average analysis to determine if there was a relationship between the reoults of foot samoling counts and

lunar chases.

This technique was described in the

previous section dealing with lunar effects upon night

counts.

Figure 3 illustrates the relationship between

the sums of the mean morning route counts for the ten

44

lunar segments treated.

This method of using the same

route means in different combinations revealed that

slightly lower daytime counts were obtained on mornings

following nights with waning moon conditions.

It ws

possible to test for differences between the results of

morning counts by regrouping foot count data into ton

three-day periods of the lunar cycle.

Analysis of

variance indicated that there was no difference between

counts for these ten lunar segments, at the five per cent

significance level.

Effects of

ulation Shifts and Increases upon Counts

High numbers of mature and yearling deer were

observed on the warmer, open., south-racing slopes at the

beginning of the study.

Deer became less evident in

those open areas as summer progressed and temperatures

became warmer.

Three such openings, along the Soap Creek

Burn, Fickreall Loop, and Skid Creek B routes, possessed

a predoninance of low grass cover where deer were easily

recognized.

A May to September reduction in deer

observed within these three route segments ranged from

57 to 80 per cent.

These shifts from the open grassy

areas, though associated with rising sunnuer temperatures,

may have been influenced by changes in deer food

preferences from the maturing herbaceous vegetation

found in the openings to browse species and thoir

associated understory plants found in adjacent areas.

However, it was interesting to note that during the first

two weeks of

ugust, when cool, cloudy weather re-

occurred after several weeks of high daytime temperatures,

there were population shifts back into these three open

areas.

This suggested that perhaps temperature changes

were more influential than food preferences in causing

deer redistributions.

Deer numbers decreased again in

these open areas with the return of warm weather.

The early June fawning season caused sizable

increases in the potential number of deer that could be

sampled.

In early July, these fawns became more notice-

able as they started to follow the does.

Iigure 7 gives

the monthly percentages of fawns seen in all deer

classified by age.

This indicates that early summer

diurnal fawn movements were more extensive than were

nocturnal movements for the same months.

The daytime

percentage of observed fawns increased to about 35

per cent of the total deer classified by the end of the

summer.

Thia firure Is somewhat biased since mature

bucks were less frequently observed In the late summer.

This tended to increase the percentage of observed fawns

for the months of August and September.

The monthly sums of mean route counts for the

eight routes which were observed May through September,

were 102, 9?, 135, 138, and 81, respectively.

The June

count drop to 9? could reflect animal shifts from the

open areas.

The accelerated activities of fawns caused

the sums of monthly moan route counts to peak in August

before dropping to a low of 81 deer in September.

Effects of Vegetation Changes upon Counts

A description of spring and summer vegetation

growth and its effects upon the ability to see deer were

discussed in a previous spotlight section.

Daytime

observations were further influenced by changes in

foliage and deer pelage color.

The color of vine maple

leaves began to change from green to reddish-orange by

midsummer.

This lessened the contrast between the

door's reddish-brown summer pelage and the abundant

vine maple.

this time.

Most grass and forb growth had matured by

This dry herbage also lessened the pelage-

vegetation contrast, which was an important clue to

locating deer in the early summer.

By September, the ability to distinguish motionless

deer became more difficult as they began to molt into

their grey winter pelage.

The mature bucks were the

first to shed their reddish-brown pelage while the

mature does were the last to undergo this change.

Comparison of Spotlight and Foot Sampling Results

This section compares the night spotlight and the

daylight foot methods of observing deer by analyzing the

A co-

variations between their repeated samplings.

efficient of variation, or relative standard deviation,

was omutd from the results of all observations

(exclusive of those obtained on foggy days) for each

Counts from

route sampled by each method of' observation.

morning and evening foot routes were combined because

their results were not significantly different.

Figure 8 compares those coefficients for the eleven

routes which were sampled by both methods.

The results

from nine of the eleven spotlight routes had less

variation between repeated samplings when compared to

daytime results obtained from the same routes.

Previous

sections discuss some of the factors possibly causing

this variation.

A day and night comparison of sums of mean route

counts for the eight routes spotlighted on the left sIde

of the vehicle were 107 and 116 for spotlight and foot

counts, respectively.

This illustrates that approxLmately

the same number of deer were seen while spotlithting the

left side of the transect as were seen along both sides

during daytime sampling.

The sum of the average deer

seen per hour of spotlight and foot sampling on these

1

Z

zrn

-I

G)0

,

oz

(fl-I

-<

a,0

U)

>0

(flfl

-n

QC)

rO

in

rr

rn-0

(0X()

0->

,i

U)

BERRY CREEK

WIND CREEK

SKID CREEK B

SKID CREEK A

RICKREALL LOOP

BALD MOUNTAIN B

BALD MOUNTAIN A

SOAP CREEK BURN

YEW CREEK A

GREEN PEAKB

GREEN PEAK A

cfl

m

o

C

oz

Oi

cji

-

S.

-

'S

o

0

c.n

Ui

a,

I

0

Ui

0

-i

COEFFICIENTS OF VARIATION

Ui

0

a,

UI

a,

0

(0

ei;-ht routes was 66 and 34, respectIvely.

This

indicates that the spotlight routes were sampled in

approximately one-half the time of the foot routes.

GL

StlM.4.'Y AJ

I.?NS

A corperison of two direct ObS-IV&t1Ori net hods of

black-tailed d.er i

enumerat.in

was oonducted under t

'.00perative Viildlif

leaerhi

esearch

e.ten )reon

of the )reofl

nit.

A ni.:ht spotli ht and a day foot observation method

were tested betw,en

resated1y samiin

arch arid September, 195?, by

the same routes.

Weeiy and

seasonal variations in counts were determined for each

method, and attapts were made to establish the causes

of these variations,

Thtals of 4254 and 2198 deer were observed along

niit s?Ctli.it kind daytime Loot routes, resoectively.

The following results were obtained from these

observations

Lffects of Peer Activity Chang

1.

upon 3ounts

iight deer activity was riot influenced by the

presence of cloudy weather.

u.mer daytime

activity was prolonged on cloudy days.

Cloudy

weather resulted in lower daytime temperatures,

and the long! er foot routes had higher counts

along their last two miles on these days.

2.

P1:hest morninc counts were obtained on clear days

when the temperature remained below 80 degrees

Fahrenheit.

3.

The presence of rain did not seem to affect

night deer activity in the spring.

Fain was so

infrequent during daytime counts that its

effects could not be measured.

4.

Viny weather caused significant decreases in

night counts.

Doer tended to 530k the leeward

slopes on these nights.

There was no difference

in daytime counts taken on 'no wind' and "breezy"

days.

5.

Significantly higher night counts were obtained

during the second and third quarters of the

lunar month.

This was at a time when night

illumination was the greatest.

Higher percentages

of active deer were also observed during these

night counts.

Daytime counts were not significantly

different when grouped into lunar month phases.

6.

Higher proportions of mature male doer were observed

during late summer nights.

This increase corres-

ponded with a reduction in the proportion of mature

bucks seen during daylight counts.

'7.

Foute sampling durinc: the predawn hours produced

lower counts than did sampling earlier in the night.

Twice as many bedded deer were seen during the

52

predawn hours.

This suggested that oounts may be

influenced by the time of night sampled.

8.

No difference existed between morning and evening

foot route counts.

Effects of Pooulation Shifts

1.

Increases upon Counts

Early summer population shifts from open south

slopes caused large reductions in route counts.

An

inverse relationship existed between mean monthly

4 p.m., or near maximum, temperatures and the sums of

mean monthly night counts.

This indicated that

population shifts resulted when increased tempera-

tures adversely influenced the deer either directly

or indirectly.

2.

Daytime counts were first influenced by the fawn

increment in July, when fawns started to follow the

does.

Night fawn observations were less frequent

than daytime observations until September, when the

fawns became more active.

Effects of Vegetation Changes upon Counts

1.

Spring and summer vegetation growth tended to conceal

the presence of deer during this study.

This was

undoubtedly responsible for some of the variation

53

between counts.

2.

Seasonal changes in color contrasts between vegetation and deer

elage influenced daytime counts.

Deer were most readily seen on sunny days in the

early summer when the deer pelage was reddishbrown and the vegetation was green.

Animals were

most difficult to see in the late summer when deer

color was grey.

Comparison of Spotlight and F00t Sampling Fesults

1.

Nine of eleven routes had less variation for night

sampling than for day sampling.

2.

Similar deer numbers were seen along the left side

of routes at night as were seen along both sides of

the sa,e routes during the day.

3.

The spotlight counts were accomplished at twice the

rate of daytime foot sampling.

From the results of this study it is recommended

that further tests of the spotlight method be undertaken.

This work should be done in the late winter and early

spring, prior to the onset of spring vegetation growth.

This would eliminate the influence which vegetation growth

has upon the ability to see deer.

Populations would still

be concentrated on open grassy slopes where counting is

easiest.

Also, early spring counts would not be

influenced by the fawn increment.

1.

Conduction deer studies with

Aldous, C1arnce M.

the use of a helicopter. Journal of ildlife

Management 20:327-328.

2.

1956.

Behavior of Columbian black-

Dasmann, P aymond F.

tailed deer with reference to poDuletion ecology.

Journal of Mammalogy.

37:143-164.

1956.

Determining structure in

Columbian b1aok-ii1ed deer pooulstions. Journal

3.

__________________,

4.

of Wildlife Management 20:78-83. 1956.

Gregory, Tappan.

yes in the night. New York,

Thomas Y. Orowell Ccmpany, 1939. 243 p.

5.

Halioran, arthur F. Management of deer and cattle

on the Aransa,s National Wildlife Refuge, Texas.

Journal of Wildlife Manement 7:203-216. 1943.

6.

Hines, William W.

Kill statistics from an

intensively hunted Columbian black-tailed daor

population in estern Oregon. Unpublished

manuscript. 1958. 13 numb. leaves.

7. Jones, H. Spencer. General astronomy. New York,

Longmans, Green and Company, 1923.

386 p.

Li, Jerome C. P. Introduction to statistical

Arbor, Michigan, Fdwards Brothers,

inference.

Inc., 1957. 553 p.

9. Linadale, Jean . and P. Quentin Tomich. A herd

of mule deer. Perkeley, California, University

of California Press, 1953. 567 p.

10. fluff, Frederick J. The white-tailed deer on the

Pisab. National Came Preserve, North Carolina.

Washington, D.C., TJS Forest Service, 1938.

8.

249 p.

11. Slivonen, Lauri and Jukka Koskimlea.

Population

fluctuations and the lunar cycle. Papers on Game

Pesearch.

22 p.

Helsinki, Finnish Game Foundation, 1955.

12.

Taylor, Walter P. The deer of North America,

Harrisburg, Staekpole Company, 1956. 668 p.

13.

u.S. \eather Bureau. Cliniatological data.

Oregon. 63:39.

1957.

14.

_______________

Oregon.

15.

6357.

Walls, Gordon L.

July 7, 1958.

Climatological data.

1957.

Letter, Berkeley, California.

APPI2,NLICFS

5?

APPJNDIX A

eek1y Schedule of Spotli.ht and ?::ot Route

Saiing from May 6 to September 21, 1957

Miles

Day

Sunday

Monday

Tuesday

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

Routes

Green Peek Unit A

Green Peak Unit B

Green Peak Unit A

Green Peak Unit a

Yew Creek Unit A

Yew Creek Unit B

Spotlight

SA

SA

Soap

Bald

Bald

Bald

SC

bC

SC

Jind Creek Drainage

Berry Creek Trap Unit

Berry Creek Trap Unit

Forest Peak

Soap Creek Pastures

2.14

2.14

5.3

2.8

5.3

14.3

IC

3.3

2.0

IA

IA

3.14

3.3

1.6

2.3

5.5

SC

SC

SC

IC

10

IC

5k-id Creek Unit

Saturday

14.8

IC

Rickreall Mt. Loop

Skid Creek Unit A

ind Creek Drainage

Cedar Creek Burn

iiles

Foot

14.8

SC

SC

SC

C

Bald Mt. Unit A

Bald Mt. Unit B

Skid Creek Unit A

skid Creek Unit B

Rickreall Mt. Loop

Spot.

IA

IA

Yew Creek Unit A

Soap Creek Burn

Oak Creek Drainage

Creek Burn

Mt. Unit A

Mt. Unit B

Mt. Unit C

Foot

5.5

1.0

2.3

2.6

CC

50

14.6

IC

IC

SC

SC

SC

Totals

SA Spotlighted alternately, early then late

SC Spotlighted at consistent time each night

IA

a1ked alternately, morning then evening

IC Walked conitent1y morning or evening

2.6

2.2

2.2

6.8

2.6

614.3