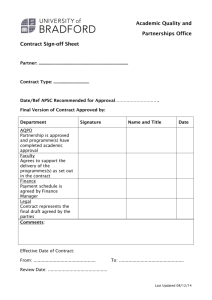

Aspect Review of the Education Authority and University ITE Partnership Arrangements (phase

advertisement