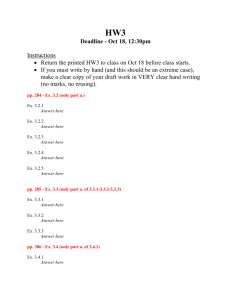

K A R D J O U R N A... H E W L © Copr. 1949-1998 Hewlett-Packard Co.

advertisement