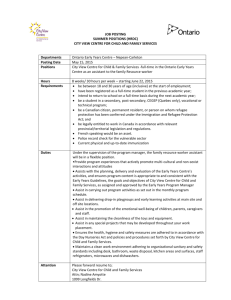

n tio ca u

advertisement