Utah Supreme Court Review - 1967 Utah Supreme Court Review Utah Law Review

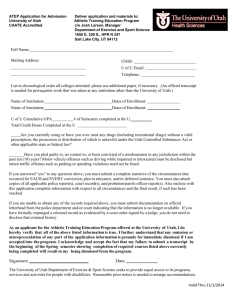

advertisement