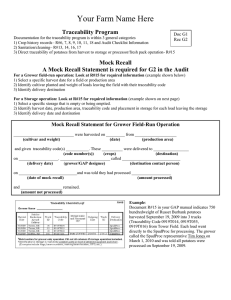

Assessing the Value and Role of Seafood Traceability from an... Value-Chain Perspective

advertisement