An evaluation of plastic flow stress models for the

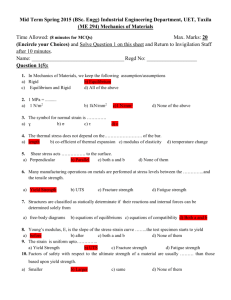

advertisement