Document 12956125

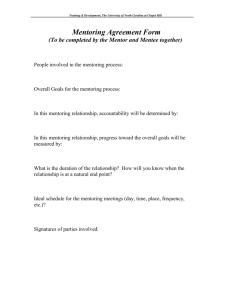

advertisement