Why collaborate?

advertisement

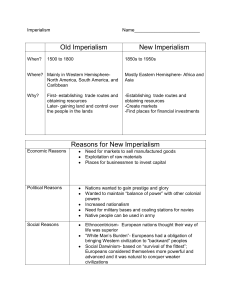

Why collaborate? According to Ronald Robinson ‘imperialism is a political function of the process of integrating some countries at some times into the international economy’ and so, he states that it was ‘the character of the collaborative mechanism that determined whether a country was allowed to remain independent or whether it was incorporated into the…empire of one of the major European powers’.1 Thus, it is possible to see that whether or not Africans were willing to collaborate strongly depended on what they were able to acquire from these new systems; collaboration rested solely on what Africans believed they would be able to reap from these imperialist powers. Moreover, the type of collaboration that occurred stemmed from the rate with which the colony’s economic and governance systems changed and Europeans undoubtedly found that certain colonies would accept their new colonial orders passively, as everyday life did not drastically change for these African peoples. Therefore, it is clear that imperialism and its subsequent collaboration with certain African societies happened because the indigenous peoples were willing – actively and passively - to accept the Europeans providing that they were able to ameliorate their situations. This could happen through the personal gains of Africans with the ‘increase [of] one’s economic status within the new colonial order’, through the advantages they received upon their acceptance of Christianity as their new religion or, because their society saw no immediate changes or disruptions.2 It seems that the main reason that Africans were willing to co-operate with the invading imperialists lay in the idea that ‘just as the Europeans used Africans to enhance their territorial domain, so indigenous societies were not averse to collaborating if it 1 Ronald Robinson, 'Non-European foundations on European imperialism: Sketch for a theory of collaboration', in R. Owen and B. Sutcliffe (eds), Studies in the Theory of Imperialism (Great Britain, 1972), p. 117. 2 Allen Isaacman and Barbara Isaacman, ‘Resistance and Collaboration in Southern and Central Africa, c. 1850-1920’, The International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol. 10:1 (1997), p. 57. 1 enabled them to expand their holdings and influence’.3 Europeans found that they could not avoid relying on Africans because of their need for interpreters and clerks and so, certain Africans who knew that resistance was futile and that modernisation was the way forward used this trust as a form of manipulation. Sir Apollo Kaggwa who was Buganda’s chief minister from 1889 to 1926 is a key example of one of these opportunists, as he dictated colonial order so that it was able to benefit him and his people. In 1900, he made a ‘profitable alliance with the incoming British and negotiated…a Uganda Agreement that ensured Buganda much autonomy, preserved its monarchy, and empowered its Christian leaders to distribute the kingdom’s land among themselves as freehold property’.4 However, while there were men like Kaggwa who wanted to collaborate in order to help not just himself but also his people profit from the invading Europeans, there were many others who were more concerned about utilising their new colonial relationships for their sole benefit. It appeared that ‘Collaborators…were concerned to exploit the wealth, prestige and influence to be derived from association with colonial government’ and this was certainly the case with Tippu Tip.5 This Swahili trader is a clear example of how Europeans and Africans collaborated so that each side utilised the other. Between 1887 and 1891, Tippu Tip was made the governor of East Congo, as the imperialists needed him to stabilise the area and to ensure that Swahili traders would be willing to work with them and in return, Tippu Tip received ‘grander notions of profit’.6 Thus, this influx of colonialism in the 19th century saw ‘a second generation of Swahili traders, led by Tippu Tip and his associates, [which] brought about a vast increase in the scale of commercial enterprise and 3 Isaacman and Isaacman, ‘Resistance and Collaboration’, p. 58. John Iliffe, Africans: The History of a Continent, Second Edition (United States of America, 2009), pp. 205-6. 5 Robinson, ‘Sketch for a theory of collaboration’, p. 134. 6 Marcia Wright and Peter Lary, ‘Swahili Settlements in Northern Zambia and Malawi’, African Historical Studies, vol. 4:3 (1971), p. 552. 4 2 a significant alteration of the political role of the foreigners’. 7 This, sequentially, showed how both sides formed these collaborations in order to exploit and gain from each other. Hence, it seems that the Europeans were willing to give certain African elites enough power to ensure that a policy of collaboration was followed. This was the case in Sudan from 1927 to 1933 when Sir John Maffey used indirect policy to give ‘official prestige, powers and patronage on the traditional chiefs and headmen’ because it was believed that in doing so, the elites would become and remain loyal to the colonial system and would thus, be willing to control the local rural communities on the imperialist’s behalf.8 Therefore, it appears that collaboration worked on two levels. This is the case due to the fact that Europeans needed African support in order to establish their rule over the colony and so, were willing to grant commissions to those Africans prepared to help. This was further supported because it was discovered that without these indigenous collaborators, the imperialists either found themselves leaving the colony or they were forced to go. And so, it would appear that collaboration relied on those Africans who were prepared to exploit this system to gain for themselves and, in some cases, for their people, thus proving that these associations were based solely on a system of manipulation and personal ameliorations. Furthermore, it is possible to see that collaboration not only occurred because of what Africans believed they could attain from the colonists, but also from the way with which this imperialism was presented to them. This can be seen through the proposition of colonisation as a form of converting these indigenous peoples to Christianity. During the 1840s and 1850s, the spread of this new religion through missionaries was the only factor in aiding imperialist expansion in Bechuanaland. However, yet again the use of religion to enforce collaboration was met with success because Africans found that there were many benefits to accepting this new order, as ‘Missionaries soon realised that Africans were most 7 8 Wright and Lary, ‘Swahili Settlements’, p. 552. Robinson, ‘Sketch for a theory of collaboration’, p. 136. 3 successfully converted when along with conversion came benefits, most notably Western education, but also health care and other forms of training’.9 Moreover, many new African Christians came from threatened groups who saw it as an escape from indigenous customs and conflicts. This was seen with the oppressed Khosian peoples of the Cape Colony who accepted missionaries are men who were sent by the Khosian God ‘to ‘show us Hottentots a narrow way, by which we might escape from the fire’’.10 And yet, this relationship was not just one sided, as missionaries themselves took advantage of the colonial infrastructure which included transportation and communication systems, legal enforcements and grants for land to expand their influence and thus, spread schools, churches and hospitals throughout the colonies. Additionally, through the creation of these networks which spread from the coast to the interior of Africa, these Christian missionaries were able to travel and expand their power deeper into the interior while maintaining their access to European supplies, at the same time. Therefore, it seems that ‘The main difference between colonial and noncolonial mission models was the amount of cultural support colonial missions received from…the host country’, proving true to the idea that even with their ‘obvious links to white expansion’ Christianity was a form of collaboration which was accepted by Africans.11 And so, as was the case with the Africans who collaborated with the Europeans for personal gain, so too did societies accept the missionaries and their associations to imperialism as, in doing so, they found themselves subject to benefits whether it was through an education or as an escape from oppression. On the other hand, while collaboration did offer benefits for those who were prepared to manipulate the systems, as Freund states the concept of collaboration 9 Nathan Nunn, ‘Religious Conversion in Colonial Africa’, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, vol. 100:2 (2010), p. 151. 10 Iliffe, Africans, p. 184. 11 H. B. Cavalcanti, ‘The Right Faith at the Right Time? Determinants of the Protestant Mission th Success in the 19 -Century Brazilian Religious Market’, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, vol. 41:3 (2002), p. 423; Iliffe, Africans, p. 184. 4 between Africans and Europeans was also ‘a process’.12 Depending on the type of collaborative mechanism that was imposed on the colonies, the occupation by the imperialists did not filter down into everyday life because there were gradual changes in the government and economic systems. This was also due to the concept of imperialism in that the colonialised states ‘represented an absentee ruling class, the metropolitan bourgeoisie, and it performed the functions of both state and ruling class in an ‘independent’ nation’.13 The fact that Africans were, therefore, willing to accommodate the invading Europeans was largely due to the imperialist’s policy of indirect rule which saw colonial authorities reigning through local and traditional African leaders in order to ensure their legitimacy. Consequently, it appears that collaboration only really affected those Africans who were considered to be elites, and this is undoubtedly seen in the book, The Dual Mandate in Tropical Africa, by Lord Lugard, a British colonial administer. In his work, he emphasised that ‘continuity…[had to] be maintained on all administrative levels’, and further proposed that in using indigenous institutions and authorities to ensure this the colonists would be able to forge ahead with improving African society. 14 Nigeria was just one of the colonies that was placed under this system, and while this strategy ultimately proved to be unsuccessful, at the beginning collaboration was able to take place. This was because the colonists’ ability to significantly interfere with the lives of Africans’ varied spatially and temporally and, in Nigeria’s case, the British chose to pay Emirs to rule on their behalf. And so, it appears that not all collaboration was done on a level which directly affected every single person and, therefore, the Europeans were able to impose their systems due to 12 Bill Freund, The Making of Contemporary Africa: The Development of African Society since 1800. Second Edition (Great Britain, 1998), p. 91. 13 Bruce Berman, ‘Structure and Process in the Bureaucratic States in Colonial Africa’, Development and Change, vol. 15:2 (April 1984), p. 161. 14 Robert O. Collins, Problems in the History of Colonial Africa, 1860-1960 (United States of America, 1970), pp. 83-4. 5 passive acceptance from certain colonies. Additionally, even those Africans who were not prepared to actively collaborate soon understood that there was no other option. In West Africa, Samori and Minilik who were well-known military resistors learnt this when they found that even though they could procure weaponry, organise training for their troops and obtain repair works, they were no match when faced with the ‘depredation of the Europeans’ with their technology and military force.15 Hence, while collaboration between the colonists and the indigenous peoples of Africa occurred because of deals made with the African elite to ensure loyalty which meant that the Europeans were inertly accommodated by their colonies, in the end it proved to be the best option. This was because resistance appeared to be futile against these more technologically advanced imperialists. Overall, it would appear that collaboration occurred due to the whole concept of what one was able to gain in terms of benefits and ultimately, power. Africans were fully prepared to co-operate with the Europeans because of their ‘ambitions for wealth, social status, political power’ and, in some cases, new institutions such as schools and churches.16 In turn, the colonial powers sought to control their territories whether it was for developmental or exploitative purposes and were thus, prepared to grant these concessions to ensure they had support and allegiance. Moreover, it was the way in which each colony’s collaborative mechanism was presented to the indigenous peoples, as through indirect rule the imperialists were accepted because change to these African societies occurred over a period of time meaning that everyday life was largely unaffected for the first fifty years of colonial rule. Additionally, as resistance attempts did appear to be futile against the better equipped Europeans, Africans found that if they were willing to collaborate instead, they were able to manipulate the system. This was certainly seen when Africans agreed to accept the Christianity in return for education, as Moshoeshoe did when 15 Bill Freund, The Making of Contemporary Africa, p. 93. Thomas Spear, ‘Neo-Traditionalism and the Limits of Invention in British Colonial Africa’, The Journal of African History, vol. 44:1 (2003), p. 27. 16 6 he ‘sent an emissary with a hundred cattle to procure a missionary, whom he promptly set to educating princes’.17 Or, even in how elites such as Tippu Tip were able to exercise power due to the strong positions they had been granted, in order to ensure the successful implementation of a new European and colonial order. Therefore, it appears that, on the whole, collaboration happened because it was not based on a system where Africans were ‘simply objects or victims of processes set in motion outside Africa and sustain only by white initiative’.18 Rather it was a co-operation which was formed on the basis of enhancing one’s position socially, economically and politically for both the imperial powers and their colonial subjects. . 17 Iliffe, Africans, pp. 183-4. Ranger, ‘African Reaction to the Imposition of Colonial Rule in East and Central Africa’, in Robert O. Collins (ed), Problems in the History of Colonial Africa, 1860-1960 (United States of America, 1970), p. 69. 18 7 Bibliography Berman, Bruce, ‘Structure and Process in the Bureaucratic States in Colonial Africa’, Development and Change, vol. 15:2 (April 1984), pp. 161-202. Cavalcanti, H. B., ‘The Right Faith at the Right Time? Determinants of the Protestant Mission Success in the 19th-Century Brazilian Religious Market’, Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, vol. 41:3 (2002), pp. 423-438. Freund, Bill, The Making of Contemporary Africa: The Development of African Society since 1800. Second Edition (Great Britain, 1998). Iliffe, John, Africans: The History of a Continent, Second Edition (United States of America, 2009). Isaacman, Allen and Isaacman, Barbara, ‘Resistance and Collaboration in Southern and Central Africa, c. 1850-1920’, The International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol. 10:1 (1997), pp. 31-62. Nunn, Nathan, ‘Religious Conversion in Colonial Africa’, American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings, vol. 100:2 (2010), pp. 147-152. O. Collins, Robert, Problems in the History of Colonial Africa, 1860-1960 (United States of America, 1970). Ranger, ‘African Reaction to the Imposition of Colonial Rule in East and Central Africa’, in Robert O. Collins (ed), Problems in the History of Colonial Africa, 1860-1960 (United States of America, 1970), pp. 68-82. Robinson, Ronald, 'Non-European foundations on European imperialism: Sketch for a theory of collaboration', in R. Owen and B. Sutcliffe (eds), Studies in the Theory of Imperialism (Great Britain, 1972. Spear, Thomas, ‘Neo-Traditionalism and the Limits of Invention in British Colonial Africa’, The Journal of African History, vol. 44:1 (2003), pp. 3-27. Wright, Marcia and Lary, Peter, ‘Swahili Settlements in Northern Zambia and Malawi’, African Historical Studies, vol. 4:3 (1971), pp. 547-573. 8