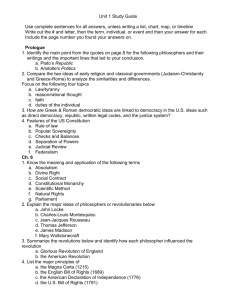

Scientific Revolution

advertisement

Handout Scientific Revolution 1. The Scientific Revolution: Term and definitions Def. Scientific Revolution: term ‘Scientific Revolution usually refers to the period from Nicolaus Copernicus to Isaac Newton (that is roughly between 1500 and the closing of the seventeenth century). It is the period in which modern ideas about nature and how it is best investigated emerge. The term “Scientific Revolution” was only minted in 1940s. In fact, the idea of a “Scientific Revolution” was initially a brain-child of a group of historians such as Herbert Butterfield, The origin of modern science (1949): “…that revolution…outshines everything since the rise of Christianity and reduces the Renaissance and Reformation to the rank of mere episodes.” Stereotypes about the natural sciences: 1. the somhow romantic image that science proceeds by “geniuses” making “discoveries” at totally unexpected moments. 2. the “great scientist” himself/herself is an autonomous agent without any connection to the social, political or economic circumstances surrounding him. 3. Science in itself value free. Current historians of science see the natural sciences as a cultural production and scientists as cultural beings. Therefore science can never be value –free. But the term is still useful because something DOES change in that period. 1. First of all the use of mathematics and measurements to give precise determinations of how the world and its parts work. 2. And second, the use of observation, experience, and where necessary artificially constructed experiments, to gain understanding of nature. Natural philosophy: a category, also known as ‘physics’. It refers to systematic knowledge of all aspects of the physical world, including living things, and in the sixteenth and seventeenth century routinely understood that world as being God’s Creation. It therefore possessed strong theological implications. Scholasticism, scholastic: A term applied to the intellectual and academic style of the medieval universities, a style stressing debate, disputation, and the effective use of canonical texts (such as Aristotle) in the making of arguments. A scholastic is a practitioner of that style. What was there to know for a natural philosopher in 1500? Aristotelian natural philosophers aimed at true, universal and God-given knowledge and therefore taken for granted. The important question for them to ask was why something was the way it was. It was not about discovery. In a sense, therefore, an Aristotelian world was not one in which there were countless new things to be discovered; instead, it was one in which there were countless already known things left to be explained. 2. Scientific Renaissance in the Sixteenth Century: Renewing Ancient Wisdom Nicolaus Copernicus, De revolutionibus orbium colestium (On the revolution of the Celestial Spheres), 1543 Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica (On the Fabric of the Human Body) The Scientific Revolution: establishing new systems of thinking and practice to deal with the natural world 1. 1633 trial against Galileo Galilei and his , Dialogue concerning two Chief World Systems. He claims his observation is no longer a hypothesis but truths. 2. René Descartes, ‘I know therefore I am’ – mechanistic philosophy, mind-body split. All phenomena could in his view be explained in terms of mathematical and mechanical concepts such as shape, size, quantity and motion. He and other mechanical philosophers saw the workings of the natural world by analogy with machinery. 3. William Harvey, Anatomical Exercise on the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Animals’, 1628. The rise of experimental philosophy. Nature can be explored and explained by experiment. 4. Isaac Newton, Philosophiae naturalis principia mathematica (Mathematical principles of natural philosophy) (1687) Conclusion: Although the investigation of nature, called natural philosophy did change beyond recognition there is one component which stayed remarkably the same: From the beginning to the end, natural philosophy involved God. Newton himself saw his endeavour as being a service to the Almighty. There were very few atheists among the natural philosophers in the sixteenth and seventeenth century. They all saw themselves as part of God governed universe that changed its structure but did not doubt its creator.