R -B A

advertisement

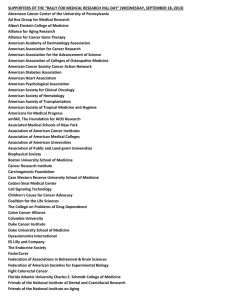

RE-BRANDING ADVOCACY: NAVIGATING MEMBER COMMUNICATIONS IN A DIGITAL WORLD Spring 2014 SIS Practicum: Cultural Diplomacy and International Exchange Jessica Giguere, Emily Heddon, Lindsay Little, Olga Sevcuka School of International Service American University TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION: THE ALLIANCE FOR INTERNATIONAL EDUCATIONAL AND CULTURAL EXCHANGE ................................................................................................................................................................5 LITERATURE REVIEW ...........................................................................................................................................7 METHODOLOGY .................................................................................................................................................... 11 ANALYSIS OF TOOLS ............................................................................................................................................ 13 REGIONAL FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS ............................................................................................................ 16 PROGRAM FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS ............................................................................................................. 18 LEVEL WITHIN ORGANIZATION FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS ................................................................... 21 VOLUME OF COMMUNICATIONS, WEBSITE, AND SOCIAL MEDIA ....................................................... 23 NEW YORK CITY INTERVIEWS ......................................................................................................................... 24 WASHINGTON, D.C. INTERVIEWS .................................................................................................................... 26 RECOMMENDATIONS .......................................................................................................................................... 29 LIMITATIONS AND LESSONS LEARNED ......................................................................................................... 33 FUTURE RESEARCH .............................................................................................................................................. 34 CONCLUSION .......................................................................................................................................................... 35 BIBLIOGRAPHY ...................................................................................................................................................... 37 APPENDIX A: ........................................................................................................................................................... 40 APPENDIX B: ........................................................................................................................................................... 51 2 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report details the analysis of the member communications of the Alliance for International Educational and Cultural Exchange (the Alliance), a 501(c)(3). The Alliance is a member-based advocacy organization with three full-time staff located in Washington, D.C. It is the only organization that advocates for issues related to international exchange and is comprised of 84 member organizations that administer international exchanges located throughout the United States. The Alliance aims to serve the informational needs of its diverse membership and employs various online tools to achieve this end. Specifically, the Alliance utilizes five online tools to communicate with its members: 1. Policy Monitor: a collection of international exchange news and policy trends, emailed to members on an as needed basis and also posted to the Alliance website. 2. Policy Monitor Weekly Digest: a weekly email that includes Policy Monitor items, as well as local news stories, Exchange Voice items posted during that particular week, and that week’s Federal Register listing. 3. Exchange Voice: located on the Alliance website, the Exchange Voice page features success stories of member organizations’ exchange participants. 4. Federal Register: member-only weekly updates on federal action regarding international exchanges, with information from the Department of State, the Department of Education, and USAID. 5. Action Alerts: email alerts that call on members to take action on urgent exchange related congressional issues. In addition to these tools, the Alliance provides information through its website and social media. The present report analyzes how members utilize information and interact with the Alliance via these tools, the website, and social media. This analysis was conducted through two channels. First, an online survey sent to 451 staff members of Alliance member organizations. Second, inperson interviews were conducted with staff of several member organizations in Washington, D.C. and New York City. Based on the results of this analysis, five key findings emerged: 1. Overall, staff members of Alliance member organizations are generally satisfied with Alliance communication and its ability to meet their organizational needs. 2. According to survey respondents, the most effective communication tools are the Policy Monitor Weekly Digest and Action Alerts. 3 3. All five tools were primarily used for general awareness, rather than research or organizational decisions. 4. In terms of the potential expansion of Alliance communication, topic-specific webinars were preferred. 5. The majority of member organization staff does not interact with the Alliance via social media. Based on these key findings, as well as an extensive literature review, short-term and long-term recommendations were identified: Short-term 1. Implement better branding for Alliance tools, as well as information on the Alliance website. 2. Create and utilize topic-specific webinars. 3. Better tailor the information and target the appropriate audience. Long-term 4. Design and implement a more robust communication strategy. 5. Target and integrate more entry-level staff members at member organizations, as well as those outside of the northeast. In addition to the information noted above, the report details the specifics of the literature review, methodology employed in this analysis, describes the limitations of the present evaluation, discussed implications, and suggests further avenues for research. 4 INTRODUCTION: THE ALLIANCE FOR INTERNATIONAL EDUCATIONAL AND CULTURAL EXCHANGE The Alliance for International Educational and Cultural Exchange is an international advocacy organization that represents 84 non-governmental organizations. The Alliance was founded in 1994 following the merger of the International Exchange Association and the Liaison Group for International Educational Exchange. The Alliance is a non-profit organization (501(c)(3)) with three full-time staff members. Every year, the Alliance also sponsors an international intern (Alliance Website). The Alliance’s member organizations, located throughout the United States, comprise the international educational and cultural exchange community. Alliance member organizations sponsor a variety of programs, such as academic exchange, high school, professional training, study/work abroad, and teacher exchange, among others. Many of these organizations receive government funding, while others are privately funded. The Alliance is unique in that it serves as the only collective public policy voice of the international exchange community. Its mission is “to formulate and promote public policies that support the growth and well-being of international exchange links between the people of the United States and other nations” (Alliance Website). In order to carry out this mission, the Alliance conducts several organizational activities. First, the Alliance advocates on behalf of the international exchange community through direct representation on Capitol Hill and through building grassroots constituencies. Second, the Alliance provides a forum where leaders of the community can discuss issues and develop cooperative approaches to address these issues. Lastly, the Alliance provides comprehensive information about issues and other matters affecting the future of the exchange field so that those in the field, as well as the general public, are aware 5 of the role that international exchanges play in domestic and international policy. The Alliance also publishes the International Exchange Locator, a resource directory of organizations in the United States that provide international exchange opportunities, including both Alliance members and non-Alliance member organizations. To provide for the informational needs of its membership and the broader international exchange community, the Alliance currently employs five online tools to communicate exchange news and information: Policy Monitor: The Policy Monitor is a collection of international exchange news and policy trends located on their website. In addition, items of particular importance are emailed out as alerts to members. Policy Monitor Weekly Digest: A weekly email that includes Policy Monitor items, as well as Local News stories, Exchange Voice items posted during that particular week, and the week’s Federal Register listing. Exchange Voice: Located on the Alliance website, the Exchange Voice webpage features success stories of exchange participants submitted by member organizations. Members submit these stories to the Alliance, whose staff edits and posts the stories to their website. Federal Register: Member-only weekly updates on federal action regarding international exchanges, with information from the U.S. Department of State, the U. S. Department of Education, and USAID. The Alliance has a paid subscription to the Federal Register, which is the daily journal of the U.S. Government. Action Alerts: Email alerts that call on members to take action on top exchange related congressional issues. Most often, Action Alerts call on members to submit letters to their 6 member of congress, using a template provided by the Alliance, which is located on the Alliance website. For example, when Congress releases budget proposals that may include cuts to international exchange programs, the Alliance sends Action Alerts to members urging them to send letters to their members of Congress outlining the importance of these programs and why funding cuts would be detrimental. In addition to these tools, the Alliance website is used to disseminate information and offers a newly created ‘members-only’ section, which allows members to change their email preferences. The Alliance also has a social media presence on Twitter and Facebook, albeit their actual engagement with social media is limited to tweeting Action Alerts and occasionally posting information on Facebook. The purpose of this study is to analyze the effectiveness of the online tools that the Alliance uses to disseminate information to their members. Specifically, the report analyzes how members utilize information and interact with the Alliance via these tools, the website, and social media. First, the methodology will be discussed, followed by an analysis of the collected data. This report will conclude with long-term and short-term recommendations. LITERATURE REVIEW The present analysis included an extensive literature review subdivided into two topics. First, research on survey methodology was reviewed with particular attention to survey design, response rates, and general best practices in survey research. The conclusions drawn from this portion of the literature review informed the design, implementation, and analysis of the survey. The second component of research focused on member-based organizations and their online communication with their membership. While research in this arena was somewhat limited, the 7 best practices that emerged through the review informed both the interview questions used during the in-person interviews and the recommendations provided at the end of the analysis. Survey Methodology An online survey was chosen early on in the planning phase of this analysis due to the ease of implementation, data collection, and data analysis. The literature review confirmed that online surveys are, in fact, becoming the norm and virtually replacing paper-based or phone surveys. However, online surveys differ from other survey methodology in a number of important ways: they are very well-suited to non-random sampling of a particular target group, they tend to appear longer than their printed counterparts, and the technical ease of creating online surveys creates the illusion that anyone can employ this survey methodology effectively (Van Selm & Jankowski, 2006). Because this analysis involved a very specific target audience for the survey, the online platform was particularly well suited to this end. Length was identified as a key factor in survey design and revisited frequently during the design phase. Finally, to avoid the pitfalls of the assumption that anyone can design online surveys, best practices of survey design were gathered through a variety of sources. Some of the best practices that were identified were: only asking question with one answer rather than multiple answers, using precise language that cannot be misinterpreted, being consistent with terminology, and being objective when posing the questions (Andres, 2013). Beyond survey design, other best practices helped inform the larger survey package and the survey platform. Research has shown that sending an introductory email prior to the distribution of a survey helps to increase response rates, while decreasing the amount of time it takes a respondent to finish a survey. In addition, providing a specific timeline and deadline for survey, 8 along with a single reminder email has also shown to positively impact response rates (Van Selm & Jankowski, 2006, p. 437). In terms of the survey platform, familiarity and simplicity emerged as the most important best practices, with one study demonstrating that the more familiar an audience is with a particular platform, the more likely they are to both open and complete it (Behr, Kaczmirek, Bandilla, & Braun, 2012). Finally, length was identified as the single most important factor affecting response rates, with shorter surveys yielding higher response rates (Andres, 2013; Behr, Kaczmirek, Bandilla, & Braun, 2012; Van Selm & Jankowski, 2006). Specifically, for surveys with a very broad audience, not targeting a specific group, response rates experienced significant drop offs beyond 15 questions. In the case of a specific audience, more questions were permitted before response rates suffered significantly, but any survey taking more than 15 minutes yielded very low response rates, which is considered anything less than 10% (Van Selm & Jankowski, 2006). Member Based Communication As previously mentioned, research on this topic is fairly limited but certain conclusions and best practices did emerge as a result of this component of the literature review. Major conclusions centered on the potential and actual usage of online platforms by member-based organizations, the importance of two-way communication when it comes to these types of organizations, and the importance of social media for advocacy and activism. One major pattern that was identified by a variety of sources was that while most organizations acknowledge and recognize the potential of Internet based platforms for aiding their communication and interaction with their members and other constituencies, few organizations are actually utilizing 9 these platforms to their full potential (Kent, Taylor, & White, 2003; McAllister-Spooner, 2009; Obar, Zube, & Lampe, 2012; Sommerfeldt, 2011; Taylor, Kent, & White, 2001). An important characteristic of the Internet is connectivity, which is especially important for organizations. Specifically, the Internet allows for alliances and other member-based organizations to easily create two important goods. The first good is connectivity, or the ability for members to communicate directly with each other and create networks. The second good is communality, which organizations help establish through the availability of a commonly accessible pool of information (Monge, 1998). In turn, these goods strengthen the alliance and aid it in its work by strengthening its networks. Connectivity can also aid organizations in establishing more channels for two-way communication between the organization and its members. This has been identified as both a best practice and an increasing trend within member-based organizations and advocacy organizations in particular. Advocacy and activist organizations typically operate with a small budget and few full-time staff that has historically limited their two-way communication with their constituencies, but the Internet provides cost effective ways to utilize the relationship building potential of online platforms (Taylor, & White, 2003). One of the most important of these online platforms is social media. One study of 169 representatives of 53 national advocacy/activist groups operating in the United States found that all of the groups are using social media in some capacity to facilitate civic engagement and inspire collective action (Obar, Zube, & Lampe, 2012). This finding is representative of a wider pattern of increased organizational use of social media both in the for-profit and not-for-profit sectors. While various organizations are still employing email alerts as a way to communicate with members and inspire action, the use of social media in addition to email has been identified 10 as a best practice, especially for grassroots activism efforts (Obar, Zube, & Lampe, 2012; Sommerfeldt, 2011). METHODOLOGY As this project focuses on the effectiveness of the Alliance’s communication tools, it was important to garner feedback directly from the staff of Alliance member organizations. With 451 individual email accounts subscribed to receive email alerts from the Alliance, the most practical way to reach such a large pool of subscribers was through an online survey. However, in order to complement survey findings with more in-depth qualitative data, in-person interviews with Alliance member organization staff were also conducted. Several drafts of the survey were submitted to the Alliance staff for their review and were discussed in-person during a period of roughly three weeks before the final version was ready for implementation. Based on best practices identified through the literature review, SurveyMonkey was selected as the survey platform because the Alliance had used it previously and Alliance members were already familiar with it. The survey consisted of 32 multiple-choice and ranking questions, but several questions also offered comment fields for those who wanted to provide more in-depth responses. The questions probed Alliance members to think about each of the five tools the Alliance uses to communicate news and advocacy issues related to international exchanges. It asked questions ranging from the frequency of use to the effectiveness of the tool. It also asked questions about the Alliance website, social media, and other ways the Alliance could facilitate communication with members from managing online forums to hosting webinars. Please see Appendix A for survey questions. The survey was initially open for five days, but was extended for three additional days to attain a higher response rate. Prior to the survey, the Alliance sent an introductory email that 11 detailed the survey contents and purpose. When the survey was extended, the Alliance also sent an extension notification email reminding members to complete the survey. Out of the 451 email accounts that received the survey, 124 responded. Blank responses and those that completed only the demographic section were eliminated because they would not add to the analysis of tool effectiveness or usage. Although certain respondents skipped specific questions, particularly those requiring ranked responses, these were not eliminated from the final analysis. As a result, 116 responses were analyzed, yielding a 26% response rate. All survey responses were anonymous. The interviews were meant to complement the survey data and were conducted in a semistructured format. The majority of the questions were open-ended to solicit more in-depth feedback on all of the topics that appeared in the online survey. The Alliance reached out to members in Washington, D.C. and New York City to set up the interviews. The options for interview dates were limited so the selection of participants was constrained by availability. Most of the interviewees were experienced professionals and many of them were senior or executive level staff. A total of 22 staff members representing 11 different organizations participated in the interviews, which lasted anywhere from thirty minutes to over an hour. Many of the interviews were conducted during or before the online survey was completed. Once the survey was closed and the notes and transcripts from the interviews were typed and compiled, the data were aggregated and analyzed to identify overall trends. First the data were analyzed by looking at each tool, and then the survey data were filtered to look more closely at themes and general trends across geographical regions, the type of programming administered by member organizations, and level of professional experience (more specifically their level within their organization) of the survey respondents. 12 ANALYSIS OF TOOLS Half of the online survey (16 of the 32 questions) dealt specifically with the online tools the Alliance uses to communicate with its members. Namely, the Policy Monitor, the Policy Monitor Weekly Digest, the Exchange Voice, the Federal Register, and Action Alerts. Three to four questions were asked about each tool, including multiple choice, ranking, and comment field questions. The ranking questions were most often skipped with response rates as low as 17% (compared with 26% for the survey overall). Excluding the ranking questions, the rest of this section had relatively low skip rates with response rates ranging between 22% and 25%, comparable to the survey overall. Based on the data gathered in this section, we can conclude that the majority of respondents were familiar with the Alliance communication tools. However, it must be noted that the survey included tool definitions to help the respondents to distinguish among the five tools. Therefore it cannot be concluded that the respondents would have recognized the tools by name alone, but in conjunction with the tool description, the proportion of respondents that were unaware of the tools was less than 5% for all but one of the tools. The percentage of respondents that were unaware of the Exchange Voice was 12%. Interestingly, the Exchange Voice is also the only tool that requires accessing the Alliance’s website in order to interact with it, supporting the finding that Alliance members do not frequent the website. Very few respondents used any of the tools on a daily basis (between 0% and 8%), however that is only an option for three of the tools: the Policy Monitor, the Exchange Voice, and the Federal Register. Items from each of those tools are included in the Policy Monitor Weekly Digest and the most highly ranked benefit of that particular tool was the compilation of 13 other information in one weekly email. Together, these findings may suggest that Alliance email traffic could be limited by relying primarily on the Policy Monitor Weekly Digest. The most frequently used tool was the Policy Monitor Weekly Digest with 53% of respondents reported they use it weekly. In terms of frequent users, meaning those that utilize the tools either daily, weekly, or bi-weekly, the Policy Monitor Weekly Digest was again the most frequently used tool, with 65% of respondents using it frequently. The nature of the Action Alerts tool differs from the rest of the tools because they are sent on an as needed basis, making a direct comparison with the other tools fairly difficult. Nonetheless, 85% of respondents said they respond to Action Alerts at least sometimes. Furthermore, 85% also said that they share Action Alerts with their networks at least sometimes and 83% state that Action Alerts are communicated in a clear and concise manner. Based on these findings, we concluded that the Policy Monitor Weekly Digest and the Action Alerts are the two most effective or successful Alliance communication tools. The least utilized tool was the Exchange Voice with the majority of respondents (54%) basically not interacting with it at all (never, almost never, and unaware). Only 17% of the respondents used the Exchange Voice frequently and 19% used it monthly. This is consistent with the finding that this is also the least known of all of the Alliance tools and the only tool that is primarily housed on the website. The Exchange Voice significantly differs from the other tools in that it is not a summary of information curated by the Alliance and distributed to its member, but rather a place for Alliance members to share their own information, namely their participant success stories. Action Alerts also differ from the other tools but they are unique in that they call upon Alliance members to take action using a service provided by the Alliance. The lack of success on 14 the part of the Exchange Voice, compared to the Action Alerts, may be due to the fact that the Exchange Voice is not providing a new or unique service to members. In other words, by providing a template for writing to members of Congress, Action Alerts succeed by providing a useful service. On the other hand, Alliance member organizations may already have a way to collect and distribute participant success stories outside of the Alliance or its network. While the Federal Register is used more frequently than the Exchange Voice, there is an interesting split in its usage. The largest group, at 38%, uses the Federal Register weekly, but a close second at 27%, almost never use it. On a larger scale, 48% are frequent users, meaning they use the Federal Register daily, weekly, or bi-weekly. On the other hand, 42% basically do not interact with the tool at all, meaning they use it almost never, never, or are not even aware of the Federal Register. This finding seems to divide users into two camps: those that use the Federal Register, use it fairly frequently; those that do not use it frequently, do not use it all. In other words, there are very few occasional users. This may suggest that this particular tool is only useful for a specific group within Alliance membership and may present opportunity for greater targeting of information. If the Alliance was able to determine which of its member organizations used the tool, it could tailor this information specifically to them and decrease email traffic to those who not need that information. Something four of the tools had in common was the purpose behind their use. Respondents overwhelmingly used all five tools for general awareness purposes, rather than organizational decisions, professional development, research, advocacy, or other. In fact, “general awareness” was selected as the primary usage for each tool by at least 50% of respondents. For the Policy Monitor and Policy Monitor Weekly Digest, 84% and 86% selected “general awareness” as the primary use respectively. The portion of the survey about Action 15 Alerts did not contain a question about how the tool was used because its purpose is inherent in its format. A secondary use for the Policy Monitor and Policy Monitor Weekly Digest was advocacy. It may be interesting to explore how organizations use these particular tools for advocacy purposes because the Alliance is an advocacy organization and the survey lacked indepth questions in this particular survey. Secondary purposes for the Federal Register and Exchange Voice were research and organizational decisions respectively. The use of the Exchange Voice for organizational decisions is consistent with a finding that emerged from the in-person interviews, namely that organizations occasionally use the Exchange Voice as a way to see what other organizations similar to them are doing and spot organizational trends. Please consult for more detailed information on what the survey revealed about each tool Appendix B. REGIONAL FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS Most of the survey respondents are based in the Northeast, which initially seemed to skew the data. When measured against the actual demographics of Alliance membership however, the regional sample sizes of respondents were fairly representative of the Alliance’s geographical membership. Of those surveyed, 66% represented the Northeast, 16% represented the West, 9% represented the South, and 9% represented the Midwest. The actual makeup of the Alliance membership is 60% from the Northeast, 21% from the West, 12% from the South, and 7% from the Midwest. Despite geographical differences, each tool is typically used for the same purposes with only slight differences in frequency of use. The South appears to use the tools with more regularity than other regions and also appears to be most engaged in responding to action alerts. 16 No statistically significant regional differences in how the Policy Monitor is used were found. It is primarily used for general awareness and most find the US Department of State News to be the most beneficial part of the tool, with all regions preferring to access the Policy Monitor via email. This preference may simply be a result of convenience because Policy Monitor emails are regularly sent by the Alliance. The Northeast, West, and Midwest regions are the primary users of the Policy Monitor Weekly Digest. The South tends to use the Digest less frequently. The survey responses suggest that the Midwest uses the Digest for advocacy more than other regions, but like the Policy Monitor, the primary use of the Digest is general awareness across all regions (78-90%). In terms of the Digest, all regions indicated that they find the compilation of information in one email most beneficial and the Weekly Federal Register listing as least beneficial. All four regions rarely access the Exchange Voice, even though it is most often read in the South. Similarly, the Federal Register is hardly used by any survey respondent. In fact, of those who read the Federal Register, primarily in the Northeast and the South, most never or almost never email Alliance staff regarding an item. This may suggest that the Exchange Voice and Federal Register are less relevant to many of the staff receiving these email alerts from the Alliance. All of the regions sometimes respond to Action Alerts. The South and Midwest tend to respond to Action Alerts more frequently and yet all regions mostly agree that the Alliance communicates Action Alerts in a clear and compelling manner that encourages action. All of the regions share Action Alerts with their networks, but again the South and Midwest are much more likely to share Action Alerts with their networks than the other regions. 17 The Alliance website is accessed most frequently in the South on a quarterly or monthly basis. It is least accessed in the Northeast. This may be due to the proximity of member organization locations to the Alliance office in Washington, D.C. and the policy sphere at-large. The South and Midwest are mostly likely to visit the member-only section of the website while most respondents in the Northeast almost never or never access member-only content and 14% did not know there was a member-only section on the website. In fact, most respondents across all regions were not aware that they could change their communication settings, though all regions generally feel that the volume of communication coming from the Alliance is “just right.” None of the regions engage much with the Alliance on Twitter and most do not engage with the Alliance on Facebook (82-93%). Out of all of the respondents, 55% of the Northeast do not think the Alliance should engage more with their members via social media, but prefer Twitter to Facebook, 70% of the West does not think the Alliance should engage more via social media, 50% from the Midwest also think the Alliance does not need to engage more via social media, and only 17% of the South thinks the Alliance should not engage more via social media. In terms of the potential expansion of Alliance communication, all regions appear to be much more interested in webinars. PROGRAM FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS Analyzing the different program areas yielded few significant results. Taking the eleven different groups separately, there was slight deviation from the average respondents. Slight deviation is generally defined as, “this group used the Policy Monitor slightly more or slightly less than the average.” There were no groups that had completely different uses for the tools nor were there groups that answered the ranking questions significantly differently from the average. 18 One possible explanation is that most organizations sponsor more than one type of program, with many sponsoring several different types of programs. For example, several organizations sponsor both Au Pair and Camp Counselor programs. Yet a different organization sponsors Professional Training and Internship programs. However, it is also possible that an organization that sponsors both Au Pair and Camp Counselor programs could also sponsor Internship programs, but not Professional Training programs. This means that clearly defining groups of programs to analyze is complex and will not be inclusive or wholly encompass all sponsors of a certain type of program. Several of the programs did correlate with each other, with high levels of respondents reporting to sponsor the same several types of programs. Using this, new groups were formed, pairing programs with a similar response rate of at least 50%. As a result, three new groups emerged: Au Pair and Camp Counselor; Citizen/Professional/Youth and Teacher Exchange; and Internship and Professional Training. Certain groups had more respondents than others and thus the differences in percentages may reflect a smaller sample size. Further, certain respondents, specifically those who claimed to sponsor several programs, may be overrepresented by having their responses analyzed multiple times. Nevertheless, the results of this analysis are as follows: Academic Exchange - 41 responses Overall, this group had slightly less use of tools than average and also had less use of the website. Au Pair/Camp Counselor - 10 responses Overall, this group is more engaged than the average with Alliance communications. Only one person responded that they were not aware of a tool (Federal Register). They also use tools in different ways and specifically, they use the Exchange Voice for organizational decisions. They engage more than average via Facebook, but not via Twitter. Citizen/Professional/Youth and Teacher Exchange - 13 responses This group is more active within the tools, especially with the Federal Register. All respondents were aware of or used all of the tools, with the exception of the Exchange 19 Voice, where three of the respondents were simply unaware of this tool. There was less use of the website and Action Alerts. This group also preferred more engagement via social media than the average. High School Exchanges – 44 responses Overall, this group reflected the average percentages of almost all of the questions. Internship and Professional Training - 33 responses This group matched the general averages in most categories. There is more frequent usage of the Policy Monitor Weekly Digest: 81% use it weekly or bi-weekly vs. 65% in the general survey. There is also more use of the Federal Register: 64.5% use it at least quarterly vs. 58% in the general survey. They access the website less than average and engage less via Twitter. These respondents were highly supportive of expanding Alliance online communication. Summer Work/Travel – 41 Responses This group used the tools more frequently than average and they varied more in the use of the tools, with the highest being for organizational decisions and research (aside from general awareness). They responded more to Action Alerts than the average. They also responded that Alliance communication aids more in their work than average: 97% Frequently/Sometimes aids in work vs. 89% in the general survey. They engage less via Twitter than average: 89% do not engage vs. 79% in the general survey. Study/Work Abroad – 31 Responses Overall, this group reflected an average use of the tools but they engage less via social media than average and would like to engage more via Facebook than average. Other – 11 Responses Overall there was slightly less engagement than average with all of the tools except for the Action Alerts, where participation was slightly higher. This group engages less via social media, and they don’t want to engage more. Because it was difficult to delineate differences in programs and analyze separate groups, the Alliance provided a different way to organize these programs: J-1 Visa Programs Au Pair Camp Counselor Internship Professional Training Summer Work/Travel Funded Programs Academic Exchange Citizen/Professional/ Youth Exchange Hybrid High School Exchange Study/Work Abroad Teacher Exchange 20 Comparing these groupings to each other, the use of the tools was almost identical. The only other deviation among the three groupings was with how often each group accesses the Alliance website. The J-1 programs accessed the website more often than the Funded and Hybrid groups. Responses to the other questions were uniform. Comparing the different programs yielded little deviation or differences in responses between the groups. Because the membership of the Alliance is so diverse, this could mean that the Alliance does not delineate program differences as a part of their information sharing. There could also be other limitations, as discussed further in later sections. LEVEL WITHIN ORGANIZATION FINDINGS AND ANALYSIS Analyzing the survey filtered through the lens of one’s level within their organization and professional experience was a bit skewed, as there was little representation from entry-level staff. Of the survey respondents, 38% represented executive level staff, 27% senior level staff, 27% were mid/managerial (none of whom represented the South), and 8% were entry-level (none of whom represented the South or West). However, most of the findings were consistent throughout regardless of one’s level within their organization and these findings showed that executive and senior level staff were more likely to use all of the tools with greater frequency than other staff levels. This finding is consistent with a greater level of engagement with executive and senior level staff on the part of the Alliance, especially via other communication channels, such as personal email and phone calls. Entry-level employees were most likely to respond to Action Alerts, however, the website does not attract many visitors, especially among entry-level staff. Further, most Alliance members across all levels within their organizations are not engaging with 21 the Alliance via social media and do not necessarily want the Alliance to engage more via social media. Staff at all four levels tend to use the Policy Monitor on a weekly basis. Most prefer to access the Policy Monitor via email. With the exception of the entry-level respondents, the Policy Monitor Weekly Digest is also used on a weekly basis (22% of entry-level respondents use it weekly; 22% almost never; 22% are not aware of this tool). All levels found the Exchange Voice and Federal Register listing to be least beneficial. The frequency of using the Exchange Voice varies across all levels with 34% of executives and 34% of mid/managerial staff almost never accessing it while 27% of senior staff access it monthly and 33% of entry-level are not aware of the tool. The Federal Register is used weekly by executives and senior level staff, but is almost never used by mid/managerial or entrylevel staff. It is primarily used for general awareness across all levels, but most levels never or almost never email Alliance staff about an item on the Federal Register. Most indicated that they respond to Action Alerts sometimes, however, entry-level staff have the best response rate. Even though 22% of entry-level professionals never respond, 22% respond every time and 22% respond almost every time. Despite the fact that most entry-level members are responding to Action Alerts, only 33% agree that it is clear, thorough, and compelling while 95% of executives indicate that it is clear, thorough, and compels one to take action, 76% of senior level staff also indicate that it is clear, thorough, and compelling, 86% of mid/managerial level indicate that it is clear, thorough, and compelling. The interviews revealed that many senior staff forward Action Alerts to entry-level staff so this may give entry-level staff more incentive to respond, but does not necessarily make Action Alerts easier to understand. All 22 levels share Action Alerts with their networks, but mid/managerial and entry-level staff are less likely to share Action Alerts with their networks. The website is accessed very infrequently across all levels, particularly entry-level professionals. However, in spite of this, executive level staff and senior level staff tend to think the website is very user friendly, while mid/managerial and entry-level staff were divided in their opinion of the user-friendliness of the website. All levels almost never access member-only content; most have not changed their communication preferences, and between 25-55% of respondents across all levels were unaware of their ability to change their communication preferences. Most (between 87-90%) members do not engage with the Alliance via Twitter, except for mid/managerial level staff, of which 41% follow the Alliance on Twitter. Roughly 50% of respondents across all levels do not think the Alliance should engage more with its members via social media, though senior level staff were more prone to want more engagement and mid/managerial were more prone to want less engagement. Executives and mid/managerial staff suggested more posts on Twitter while senior level and entry-level staff preferred more activity on Facebook. If the Alliance were to expand its communication, all levels (82-92%) would like to see webinars on policy issues, best practices, compliance, etc. VOLUME OF COMMUNICATIONS, WEBSITE, AND SOCIAL MEDIA The majority of respondents felt that the volume of communication that the Alliance shares is “just right”. In addition, about 90% felt that the information provided by the Alliance aids them in their work "sometimes" (50%) and “frequently” (39%). Most respondents do not frequent the website, with 34% reporting that they only access the website on a quarterly basis and 32% almost never access the website. Despite this, 42% of 23 respondents find the website to be very user-friendly and 30% find it to be somewhat user friendly. In terms of accessing member-only content on the website, 69% access this content never, almost never, or on a quarterly basis. When asked if the respondent had changed their user-preferences, 58% indicated that they have not while 31% did not know that this was an option. The majority of respondents do not engage with the Alliance via social media, with 85.5% of respondents not engaging through Facebook and 80% not engaging with the Alliance through Twitter. Of the respondents who do engage via Facebook and Twitter, the extent of their engagement is either liking the Alliance’s Facebook page or following the Alliance’s Twitter posts. When asked if the Alliance should engage more on social media, 52.8% replied no, the Alliance should not engage more, while 27% want more posts of Twitter and 25.7% want more Facebook posts. NEW YORK CITY INTERVIEWS Interviews conducted in New York City were with staff from five Alliance member organizations. There were three mid-level staff from Cultural Vistas, three senior level staff from InterExchange, two senior level staff from the German-American Chamber of Commerce, one mid-level and one entry-level staff member from the Scandinavian-American Foundations, and one mid-level staff from the French-American Chamber of Commerce. The interviews highlighted the findings in the survey and provided more context to the survey data. The interviewees generally did not know the difference between each individual communication tool and referred to them as “Alliance Emails.” They also said they did not know the difference between the Policy Monitor and the Policy Monitor Weekly Digest. Most said that 24 they use the tools for general informational purposes rather than for organizational decisions, although the mid-level staff indicated that they use Alliance communication for research and professional development purposes. The general findings of the interviews pointed towards regular use of Action Alerts. Most said that if the Action Alert was specific to the types of programs their organization sponsors, they would take time to send a letter to their member of Congress. They also forward Action Alerts to their professional and personal networks. Most interviewees found the template for Action Alerts very easy to use and appreciate the Alliance making it easy to take action. The response received from the interviews regarding Action Alerts reflected the responses gathered in the quantitative survey. The Alliance website was not used as often as the email-based tools. Most found the site relatively easy to use, reflecting the results from the survey. Most staff indicated that they use the website solely for finding information about other member organizations or event information. The members-only content is very rarely accessed and the staff would only be interested in Members Corner as a repository for information such as presentations for conferences and meetings, or for a discussion forum. Many of the staff interviewed expressed an interest in an online forum that promotes interaction among member organizations. They suggested a message board or online discussion thread that allowed members to share best practices and discuss pressing topics in the field. Suggestions for the form it would take and the way it would be moderated were varied. One of the organizations represented by interviewees already participates in monthly regional phone calls of this nature. There was also shared skepticism from senior level staff about the extent to which member organizations could use this tool given the fact that many member organizations 25 compete against each other for funding. Overall, the lower level staff expressed unreserved support for this type of option. Overall, those interviewed expressed that they do not interact with the Alliance on social media and did not express interest in doing so. Some interviewees indicated that all social media engagement is funneled through their communications team and that they could not interact at an organizational level. If social media engagement is managed in a similar way at other Alliance member organizations, this may explain the similar survey finding on the lack of interest in engaging with the Alliance. Some interviewees felt that they interacted enough with the Alliance over the phone and did not have personal social media accounts that would enable social media engagement with the Alliance on a personal level. Further, some interviewees did not have social media accounts either and thus did not interact with the Alliance nor felt they did not have the capacity to add more engagement with the Alliance. Some interviewees, however, feel that the Alliance’s presence on social media allows for pressuring board members to create a social media presence for their own organizations. Most interviewees again expressed overall satisfaction with Alliance online communications. Specifically, they indicated that they especially appreciated that the Alliance filters important information related to their field and that they relied on the Alliance to provide them the information they need both to stay informed and to make important organizational decisions. WASHINGTON, D.C. INTERVIEWS Staff members from four Alliance member organizations were interviewed in Washington, D.C. Four mid-level staff were interviewed from IREX, two mid-level staff from World Learning, one mid-level and one senior-level staff from American Councils for 26 International Education, and three mid-level staff from Global Ties U.S. The findings were consistent with the survey and also with the interviews conducted in New York City. Most of the interviewees were satisfied overall with the Alliance communication tools, but were not able to differentiate between each tool and had differing opinions about the amount of information shared or the way in which the information is shared. One of the interviewees considered emails to be “lengthy and scattered” while another referred to the tools as “timely and helpful.” All the interviewees expressed that the emails sent by the Alliance have good and useful information. Some would like to see shorter emails or less “budget speak,” suggesting there is a slight learning curve to the language used by the Alliance. Some would like the option to receive fewer emails from the Alliance, but others are very satisfied with the information they receive and find the emails very interesting. Some of the interviewees said they do not have time to read the Policy Monitor, find it vague, or merely skim over it. As for the Policy Monitor Weekly Digest, many claimed to find it a useful resource. The Exchange Voice stories were interesting to most of the interviewees, but they said that the process of posting stories was too complicated and there was at least one person who did not know anything about the Exchange Voice. It was also suggested that Exchange Voice stories are too “touchy-feely” and that stories that share more direct impact on exchange participants would be more interesting. Almost everyone interviewed in Washington, D.C. would like to opt out of the Federal Register. Grants.gov, an electronic service that houses information for government grants, has proven, for some, to be more useful than the Federal Register. Action Alerts are useful, though some of the interviewees did not quite understand the need for or the benefit of advocacy until participating in Advocacy Day. Interviewees who had participated in Advocacy Day were more likely to respond to Action Alerts, though a few people 27 would like Action Alert emails and sample templates for Congressional letters to be shorter. One interviewee described the text of the letter template as “long and intimidating.” The website does not appeal to many interviewed in Washington, D.C. Of those interviewed, only one or two had visited the website and had trouble navigating the site. One interviewee did not find the website user friendly and mentioned that it was difficult to find information. Another interviewee said they tend to call or email an Alliance staff member, even when the information is likely on the website. Member-only content was only used in conjunction with Advocacy Day. The interviews also revealed that most were not interested in interacting with the Alliance through social media. It was suggested that Exchange Stories could be posted on Facebook or that a larger presence on Twitter may be helpful. One interviewee said, “if I saw it [stories] on Facebook, I probably wouldn’t read it as thoroughly, but it would probably reach a broader audience.” Another commented that Twitter could be used more effectively with better linkages between the Alliance handle and the handle of those who are being reached out to as opposed to relying on hashtags. None of the interviewees expressed a strong interest in connecting with other member organizations. As one put it, “we are competitors, it gets tricky.” Interviewees identified Advocacy Day as sufficient in terms of connecting with other member organizations. However, some interviewees would welcome other ways to engage with other members. It is important to note that most of those interviewed were in either mid-managerial, senior level, or executive positions at their organizations so it is possible that these professionals already have an established network in the field. 28 Overall, the staff interviewed at Alliance member organizations based in Washington, D.C. are very satisfied with Alliance communication. They find the news to be relevant and timely and one of their biggest sources of exchange news and information. RECOMMENDATIONS While the survey shows that the Alliance’s online communications generally satisfy their members’ needs, several improvements could be made. The recommendations are subdivided into short-term and long-term suggestions. Considering the limited capacity of the Alliance, short-term recommendations may be more feasible. If the Alliance were ever to expand either through increased funding, full-time staffing, or internships, long-term recommendations may become more feasible. Keeping capacity in mind, the recommendations are as follows: Short-Term Recommendations: 1. Branding 2. Webinars 3. Target and Tailor Information Long-Term Recommendations 4. Communications Strategy and Branding 5. Target Entry-Level Staff and Different Regions Short-Term Recommendations Branding Both the surveys and interviews show that staff members of member organizations do not clearly understand the differences between Alliance communication tools and their uses. Several staff pointed out that they did not know the difference between the Policy Monitor and the Policy 29 Monitor Weekly Digest and other staff members said that they look at every email from the Alliance under the category of “Alliance Communication.” Clearer branding of each tool may be boost tool awareness, recognition, and use. For example, the Policy Monitor does not include only items pertaining to policy, but is rather a compilation of policy items, Congressional news, and media reports pertaining to the field of international educational and cultural exchange. A name that is reflective of the variety of items it includes, could help create a stronger brand for the Policy Monitor, increasing its recognition, while also differentiating it from other Alliance tools, and potentially, even increasing its use. The Policy Monitor Weekly Digest also includes many items from the Policy Monitor, as well as items from other tools. Further, the most beneficial aspect of the Weekly Digest was that it was a compilation of important information throughout the week condensed into one email. Shortening the name to “Weekly Digest” or “Alliance Weekly Digest” could eliminate confusion with the Policy Monitor and highlight its best feature, a compilation of information. There was also a similar lack of clarity with the Alliance website. Very few people were aware of the members only section of the website and those that were, did not understand what information could be accessed there. By clearly delineating the purposes and target audience of each tool and by naming them accordingly, the Alliance could help their members use the tools more effectively and tailor their own information through the members only section of the website. Webinars Many of the staff of the member organizations interviewed suggested that they would like ways to interact with other member organizations and to have more two-way communication 30 with the Alliance. This is consistent with both the trends and best practices in the field identified in the literature review. The survey also supported this finding, as 87% suggested they would support webinars that focused on specific topics such as policy issues, best practices, and compliance. If the Alliance was to implement webinars, it could produce the first one as an introduction to the organization, how it interact with legislators and how the federal budgeting process works, including how this process affects Alliance member organizations. This webinar could be used to introduce entry-level staff to the work of the Alliance and explain the purpose of Alliance communication. Another possible webinar topic would be providing an overview of the Alliance communication tools, their purposes, and how to change preferences on their website. Target and Tailor Information One of the most prominent issues identified was that Alliance communication lacked program-specificity and that staff members at Alliance member organizations had to read each item to decide whether it pertained to them. While certain staff members explained that they like to read each item to ensure that they have a complete picture of the policy landscape, others felt that it was too time consuming to read through every item. The Alliance could further tailor information to specific target audiences by including more specific information in email subject lines. They could also better advertise the options that members have of changing their specific preferences on the website. Many did not know that they could change preferences in terms of the program specific emails they receive. If possible, it may also be helpful to increase the number of options that subscribers have in terms of the types of emails they receive from the Alliance. 31 Long-term Recommendations Communications Strategy and Branding As with any member-based organization, the Alliance may benefit from the creation and implementation of a more robust and all encompassing communication strategy. The confusion surrounding the specific tools and their purposes further highlights the potential benefits of having a clear strategy for each tool. A fully comprehensive communication strategy may also better define the scope of Alliance communication, both in terms of their member organizations and their larger communication as an advocacy organization. As an association of other organizations, communication is a critical aspect of the work of the Alliance. The development of a long-term communications strategy would help eliminate confusion and allow the Alliance to communicate more effectively and more easily with their member organizations. Tailor and Target Entry-Level Staff and Regions The largest gap in data collection came from a lack of responses from entry-level staff. A potential explanation for this gap may have emerged during the in-person interviews when senior level staff suggested that they filter Alliance communication for their employees, limiting the amount of information they may be able to access. One aspect of the Alliance’s work is building grassroots constituencies and while each organization is characterized by its own flow of information, entry-level staff represent the largest group within most organizations. Utilizing larger networks to build support for international exchanges has the potential to boost the impact the Alliance has on policy. In this way, entry-level staff may represent a source of untapped potential for the Alliance, as well as the wider exchange community. Furthermore, the majority of entry-level staff are Millennials that research has identified as an active generation that has the ability to rally in support of important social causes. 32 One way for the Alliance to specifically target entry-level staff of member organizations is to develop a more robust social media presence, which also has the potential to be much more wide-reaching as information is spread beyond professional networks to friends and family. Other potential strategies include developing materials to familiarize entry-level staff with the role of the Alliance and the international exchange policy sphere, as well as creating forums for member interactions, and advocating for the increased participation of entry-level staff with their member organizations. There was also a disparity in the amount of communication between the Alliance’s communication with Northeast-based organizations and its communication with organizations based throughout the rest of the country. While the Alliance is currently making an effort to reach out and travel to member organizations located throughout the country, including regionbased targeting of information is recommended. LIMITATIONS AND LESSONS LEARNED As with any research project, there were several limitations that needed to be factored into the final analysis. While survey design was based on best practices, a few changes to the final design may have yielded a more complete data set. One of the main factors affecting the response rate was the inclusion of ranking questions in the midst of simple multi-choice questions. The ranking questions were often skipped, leading to a lower response rate of 17% for the ranked questions vs. the 26% overall response rate. In addition, none of the questions were forced choice or required an answer. This allowed respondents to essentially pick and choose what they wanted to answer and again limited the data collected. ‘Skip logic’ was also not employed in the survey meaning respondents were presented with every question, which included multiple questions per communication tool. If a respondent 33 did not use that particular tool, or had never heard of it, they would still be required to answer all of questions regarding that tool. In other words, if a respondent did not use a tool, they were forced to answer “I do not use/I am not aware of this tool” multiple times. Using skip logic, if the respondent identified that they did not use the tool, all subsequent questions about that tool would be automatically skipped. In the case of this survey, it would have reduced the number of questions for those respondents who did not use a particular tool and may have resulted in a higher rate of completed surveys. Although there was an overall response rate of 26%, there was not much diversity in terms of the career level of the respondents. The majority of the respondents were at the executive or CEO level (38%), while the least number of respondents were part of the entry-level group (8%). Given that most of the respondents were in high-level career positions, the data collected may not accurately reflect Alliance membership. Time constraint was another limitation of this project. From the first meeting with the Alliance to the final product, which encompassed the design, implementation and analysis stages, there was a timeline of about three months. This short timeline impacted the depth and scope of the study. The various sections of the survey (communication tools, social media, website, volume of communication, etc.) could have each been separate studies. In order to best to address the needs of the Alliance, the study took a broad approach. Ideally, the study could have included follow-up research on the findings. FUTURE RESEARCH The regional breakdown of the survey respondents was reflective of Alliance membership ratios, with most respondents concentrated Northeast region. However, the 34 Northeast encompasses many states as well as numerous metropolitan areas. While this survey did not collect data to specify where in these regions respondents were located, it may be beneficial to know where respondents are concentrated, especially because Washington, D.C. and New York City are both part of this region and most likely yielded more respondents than other parts of the region. More specific data on Alliance membership may have led to additional recommendations on ways to better target specific groups. The Alliance members work across a wide range of international educational and cultural exchange programs. These programs have different funding streams, which may lead to differences in informational needs. Having more information on specific member groups may allow the Alliance to better serve those diverse needs. Lastly, this report shows who is using these communication tools, why these tools are used, what tools are being used and how often they are used. Further research should focus on ‘how’ these tools are used. For example, advocacy was identified as a common secondary use for several tools, further research could focus on how Alliance member organizations are using the tools specifically for advocacy. CONCLUSION The present analysis concluded that Alliance member organizations are generally satisfied with Alliance communication. They appreciate the information that the Alliance provides and are satisfied with their communication tools. No serious re-design of any aspect of Alliance communication is necessary, rather, a few targeted interventions aimed at improving the tools and the website are recommended. These changes can occur in the short-term, keeping the limited capacity of the Alliance in mind. If capacity were ever to increase, long-term 35 recommendations could be implemented in order to take Alliance communication to the next level. Aligning these changes with the best practices in the field would surely yield positive results both for the Alliance and its diverse membership. 36 BIBLIOGRAPHY "About the Alliance." Alliance for International Educational and Cultural Exchange. (2013). Retrieved from http://www.alliance-exchange.org/about-alliance. Blair, J., Czaja, R. F., & Blair, E. A. (2013). Designing Surveys: A Guide to Decisions and Procedures. SAGE. Bruning, S. D., Dials, M., & Shirka, A. (2008). Using dialogue to build organization–public relationships, engage publics, and positively affect organizational outcomes. Public Relations Review, 34(1), 25–31. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2007.08.004 Burstein, P. (2014). American Public Opinion, Advocacy, and Policy in Congress: What the Public Wants and What It Gets. Cambridge University Press. Cull, N. J. (2010). Public diplomacy: Seven lessons for its future from its past. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy, 6(1), 11–17. doi:10.1057/pb.2010.4 Hestres, L. E. (2013). Preaching to the choir: Internet-mediated advocacy, issue public mobilization, and climate change. New Media & Society, 1461444813480361. doi:10.1177/1461444813480361 McAllister-Spooner, S. M. (2009). Fulfilling the dialogic promise: A ten-year reflective survey on dialogic Internet principles. Public Relations Review, 35(3), 320–322. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2009.03.008 McKeever, B. W. (2013). From Awareness to Advocacy: Understanding Nonprofit Communication, Participation, and Support. Journal of Public Relations Research, 25(4), 307–328. doi:10.1080/1062726X.2013.806868 37 Park, H., & Reber, B. H. (2008). Relationship building and the use of Web sites: How Fortune 500 corporations use their Web sites to build relationships. Public Relations Review, 34(4), 409–411. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2008.06.006 Prakash, A., & Gugerty, M. K. (2010). Advocacy Organizations and Collective Action. Cambridge University Press. Selm, M. V., & Jankowski, N. W. (2006). Conducting Online Surveys. Quality and Quantity, 40(3), 435–456. doi:10.1007/s11135-005-8081-8 Sommerfeldt, E. (2011). Activist e-mail action alerts and identification: Rhetorical relationship building strategies in collective action. Public Relations Review, 37(1), 87– 89. doi:10.1016/j.pubrev.2010.10.003 Stamatov, P. (2010). Activist Religion, Empire, and the Emergence of Modern Long-Distance Advocacy Networks. American Sociological Review, 75(4), 607–628. doi:10.1177/0003122410374083 Stroup, S. S., & Murdie, A. (2012). There’s no place like home: Explaining international NGO advocacy. The Review of International Organizations, 7(4), 425–448. doi:10.1007/s11558-012-9145-x Taylor, M., Kent, M. L., & White, W. J. (2001). How activist organizations are using the Internet to build relationships. Public Relations Review, 27(3), 263–284. doi:10.1016/S0363-8111(01)00086-8 Wallace, E., Buil, I., & De Chernatony, L. (2012). Facebook “friendship” and brand advocacy. Journal of Brand Management, 20(2), 128–146. doi:10.1057/bm.2012.45 Weible, C. M., Sabatier, P. A., Jenkins-Smith, H. C., Nohrstedt, D., Henry, A. D., & deLeon, P. (2011). A Quarter Century of the Advocacy Coalition Framework: An Introduction to 38 the Special Issue. Policy Studies Journal, 39(3), 349–360. doi:10.1111/j.15410072.2011.00412.x 39 APPENDIX A: THE ALLIANCE MEMBER COMMUNICATIONS SURVEY QUESTIONS 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 APPENDIX B: THE ALLIANCE MEMBER COMMUNICATIONS SURVEY RESULTS 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84