Eliminating Female genital mutilation An interagency statement OHCHR, UNAIDS, UNDP, UNECA, UNESCO,

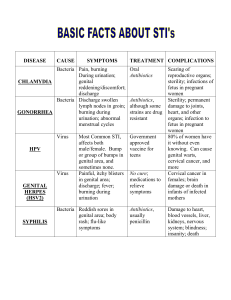

advertisement