Education 5 UCL SCHOOL OF LIFE AND MEDICAL SCIENCES

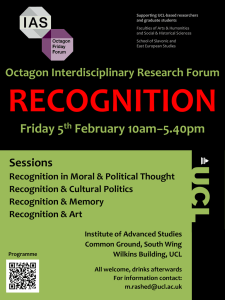

advertisement