Why Prohibition?

advertisement

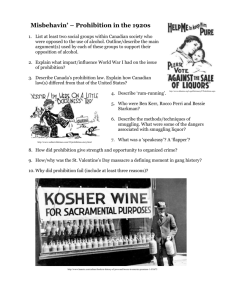

Why Prohibition? Why did the United States have a prohibition movement, and enact prohibition? We offer some generalizations in answer to that question. Prohibition in the United States was a measure designed to reduce drinking by eliminating the businesses that manufactured, distributed, and sold alcoholic beverages. The Eighteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution took away license to do business from the brewers, distillers, vintners, and the wholesale and retail sellers of alcoholic beverages. The leaders of the prohibition movement were alarmed at the drinking behavior of Americans, and they were concerned that there was a culture of drink among some sectors of the population that, with continuing immigration from Europe, was spreading. The prohibition movement's strength grew, especially after the formation of the Anti-Saloon League in 1893. The League, and other organizations that supported prohibition such as the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, soon began to succeed in enacting local prohibition laws. Eventually the prohibition campaign was a national effort. During this time, the brewing industry was the most prosperous of the beverage alcohol industries. Because of the competitive nature of brewing, the brewers entered the retail business. Americans called retail businesses selling beer and whiskey by the glass saloons. To expand the sale of beer, brewers expanded the number of saloons. Saloons proliferated. It was not uncommon to find one saloon for every 150 or 200 Americans, including those who did not drink. Hard-pressed to earn profits, saloonkeepers sometimes introduced vices such as gambling and prostitution into their establishments in an attempt to earn profits. Many Americans considered saloons offensive, noxious institutions. The prohibition leaders believed that once license to do business was removed from the liquor traffic, the churches and reform organizations would enjoy an opportunity to persuade Americans to give up drink. This opportunity would occur unchallenged by the drink businesses ("the liquor traffic") in whose interests it was to urge more Americans to drink, and to drink more beverage alcohol. The blight of saloons would disappear from the landscape, and saloonkeepers no longer allowed to encourage people, including children, to drink beverage alcohol. Some prohibition leaders looked forward to an educational campaign that would greatly expand once the drink businesses became illegal, and would eventually, in about thirty years, lead to a sober nation. Other prohibition leaders looked forward to vigorous enforcement of prohibition in order to eliminate supplies of beverage alcohol. After 1920, neither group of leaders was especially successful. The educators never received the support for the campaign that they dreamed about; and the law enforcers were never able to persuade government officials to mount a wholehearted enforcement campaign against illegal suppliers of beverage alcohol. The best evidence available to historians shows that consumption of beverage alcohol declined dramatically under prohibition. In the early 1920s, consumption of beverage alcohol was about thirty per cent of the preprohibition level. Consumption grew somewhat in the last years of prohibition, as illegal supplies of liquor increased and as a new generation of Americans disregarded the law and rejected the attitude of self-sacrifice that was part of the bedrock of the prohibition movement. Nevertheless, it was a long time after repeal before consumption rates rose to their pre-prohibition levels. In that sense, prohibition "worked." We have included a table of data about alcohol consumption. We also present some data in graphic form, including the consumption of beer in gallons, the consumption of distilled spirits in gallons, and the consumption of absolute alcohol in gallons for beer and spirits, and, in total, for all beverage alcohol. We also have some separate data for malt beverage production (beer). Department of History , 230 West 17th Ave 106 Dulles Hall Columbus, OH 43210-1367 186 University Hall 230 North Oval Mall Columbus, OH 43210 Email: humanities@osu.edu The College of Humanities and The Ohio State University takes your privacy seriously. Please read our Privacy Policy for more information. This Web site, all content and related materials are ©2003-2009 by the Department of History, the College of Humanities and The Ohio State University. If you have difficulty accessing any portion of this site due to incompatibility with adaptive technology, or if you need the information in an alternative format, please contact History Webmaster at history@osu.edu .