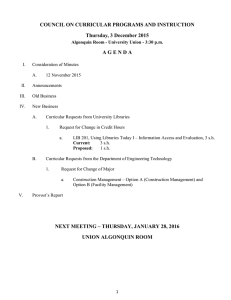

CARLETON COLLEGE Curricular Uses of Visual Materials: A Mixed-Method Institutional Study A

advertisement