THE COHEN INTERVIEWS – EILEEN YOUNGHUSBAND

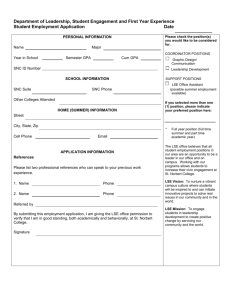

advertisement