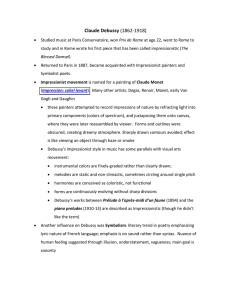

DEBUSSY’S PARIS DE

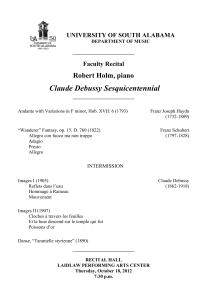

advertisement