Lyrics of the French Renaissance: ...

advertisement

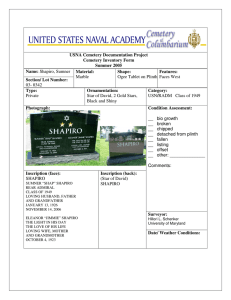

Lyrics of the French Renaissance: Marot, Du Bellay, Ronsard, English versions by Norman R. Shapiro, introduction by Hope Glidden, notes by Hope Glidden and Norman R. Shapiro (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002) 352 pp. ISBN 0300-08759-4 The present volume offers a selection of the writings of three of the best known poets of the sixteenth century; the texts are given in French with facing transposition into modern English. For each of the authors Norman Shapiro has selected pieces across the range of their poetic compositions. Thus for the rhétoriqueur Clément Marot, we have a ballad, seven rondeaux, eleven chansons, two elegies, four verse epistles, one hymn, and over thirty epigrams. For the “poet of exile”, Joachim Du Bellay, the choice goes beyond the well-known Regrets, covering also some sonnets from the Antiquitez de Rome and pieces drawn from Du Bellay’s love sequences and mixed recueils. For Ronsard, the chief of the trend-setting Pléiade, there are over fifty pieces including love sonnets, but also several odes, epigrams, epitaphs and other pieces of occasional poetry. In his English versions, Shapiro – an experienced translator of French verse – endeavours to “transmit[] to the sensitive reader an aesthetic mood similar to […] the one experienced by a reader of [the] original” (p. xxiv). Preserving, as much as possible, text volume or form and rhyme, the translator abandons any “slavish” renderings of the French in favour of readable and accessible English. On the whole, this strategy works, but on occasion the solemnity of a Bellayan sonnet or Ronsardian ode has been sacrificed to the imperative of stylistic modernity. Shapiro is at his best, however, in the epigrammatic mode: his reworkings of some of Marot’s rondeaux and épigrammes, of Du Bellay’s Jeux Rustiques or of Ronsard’s blasons – his “sexual body kept good company with his writing hand” (p. 17)! – unlock the delights of the French poetic language with wit and deceitful ease. A sparing apparatus of explanatory notes compiled by Shapiro and the author of the introduction, Hope Glidden, provides some necessary enlightenment on persons, themes or significant textual echoes. If, generally speaking, the lay-out of the poems is neat and airy, it is regrettable that in the case of Du Bellay’s “Nouveau venu qui cherches Rome en Rome” (p. 184), one of his most polished sonnets, the notes have pushed the final tercet over the page (p. 186): for it is one of the sonnet form’s great characteristics that it can (and should) be taken in at a glance, inviting the reader to appreciate the construction of the poem as a whole. Similary, a few illustrations, chosen mostly for their picture value rather than their direct connection to the original text, do embellish the book, but it would have been worth foregoing the 1 illustration on p. 369, in order to have Ronsard’s “Imitation de Martial” (p. 368) faced directly by Shapiro’s English (p. 371). The introduction by Hope Glidden sketches the French literary (poetic) scene of the sixteenth century. The lay reader will no doubt find this overview helpful and, on the whole, factually informative. The specialist will note a few lapses and, more importantly, the perpetuation of a number of outdated ideas and interpretations. For instance, the word illustration (meaning “exaltation” or “glorification”) in the title of Du Bellay’s pamphlet Defense et illustration de la langue françoyse appears misunderstood, and it is rather naïvely stated that “Du Bellay’s feelings before the decay of Rome cannot be doubted” (p. 12). Yet research in the field has clearly established the extent to which Du Bellay constructed his exiliar persona, and how he was catering to French expectations (including Ronsard’s). Though mention is made of Du Bellay’s imitation of the Neo-Latin poet Andrea Navagero in the Divers Jeux Rustiques (p. 13), there is a complete disregard for his Latin Poemata, written in parallel to the “French” Roman collections, and for the Angevin’s indebtedness to the Elegiae of Janus Vitalis, crucial for a correct understanding of “Nouveau venu qui cherches Rome en Rome” and (more broadly) of Du Bellay’s apparent melancholy. Admittedly, it is all too easy, and no doubt greatly unfair, to judge this volume just by specialist standards: it does not pretend to advance seizièmiste scholarship, but, as the blurb on the dustjacket suggests, to provide pleasure for many readers. Nor must we forget that for many of the poems presented here, there are no other English translations readily available. Students and general readers who take this handsome volume to hand, will thus find that, for all its flaws, Shapiro’s collection opens a new door onto the colourful field of French Renaissance poetry. Dr Ingrid de Smet, University of Warwick 2